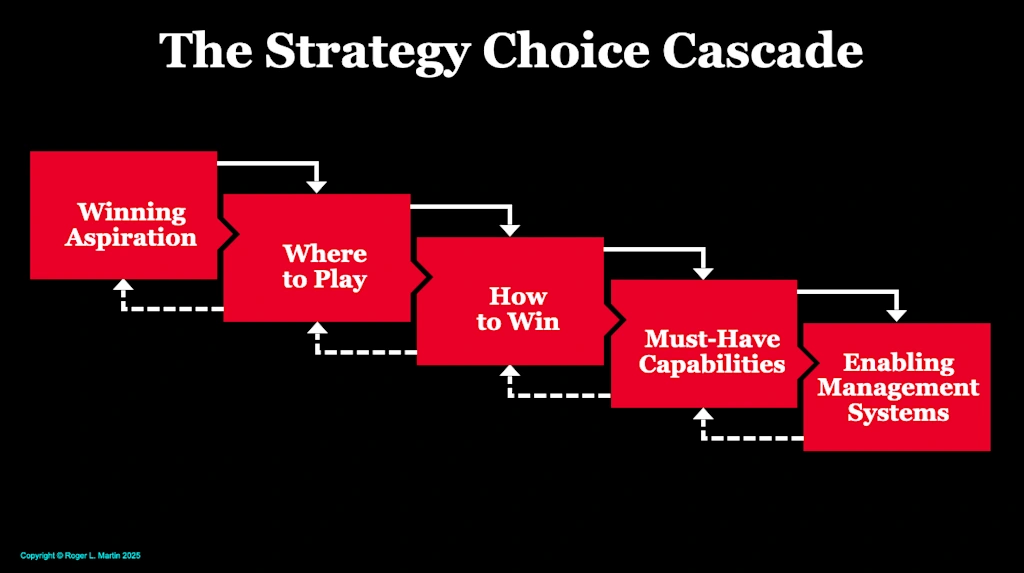

If I were to grade the five boxes across every Strategy Choice Cascade that I have ever seen, the How-to-Win (HTW) box would get the lowest grade—even lower than Enabling Management Systems, which is the least understood box. To remedy the weakness, I am dedicating this Playing to Win/Practitioner Insights (PTW/PI) to Why the How-to-Win Strategy Choice is So Hard: How to Overcome the Challenge. And as always, you can find all the previous PTW/PI here.

Key feature of weak HTW choices

I have talked extensively about the key weakness of HTW choices both in a previous piece in this series, From Laudable List to How to Really Win, and in my viral video, A Plan is Not a Strategy. The weakness is that the so-called HTW is in fact a list of initiatives, one that doesn’t pass the key test of strategy: Is the Opposite of Your Choice Stupid on its Face? That is, it is a set of things that are utterly sensible but don’t add up to a strategy that wins, and therefore won’t compel desired customer action. Considered another way, it is a list of pixels, not a portrait.

This, by the way, is a core problem manifested in the popular strategy tool called the OGSM—which stands for Objectives, Goals, Strategy, and Measures. As I have discussed before in this series, P&G is known for its use of the OGSM for strategy and since I am known for my longtime involvement with P&G, people think that either OSGM is my tool, or I am a proponent of it. Neither is true. I had nothing to do with the development of the tool, and I find it not to be a tool for good strategy—especially for HTW. In the classic OGSM, the S is a list of initiatives, generally called “strategies”—a term I hate (which I explain in this piece)! I had to work hard (along with AG Lafley) at P&G to convert the S in OGSM to something useful—and related to strategy.

Why is How-to-Win so weak?

I think there are at least four reasons why HTW is so generically weak.

Unhelpful Top-of-the-Cascade Choices

Logically, Winning Aspiration (WA) and Where-to-Play (WTP) sit before HTW in the Strategy Choice Cascade. In this respect, they set the context for HTW—and they generally don’t set it particularly well.

WA choices err in one of two unhelpful ways.

First, WA is often unrealistic. We aspire to be the best IT company in world. We aspire to be the most innovative company in the world. For some companies, these may be fully realistic WAs for which there are entirely plausible HTWs. But for most, there is no plausible HTW for such an over-the-top WA, so whatever the company puts in its HTW box, it can’t match with the WA. For example, if you are a modestly sized company, chances are that you won’t be able to spend the resources necessary to be either the best IT or most innovative company in the world. Given the impossibility of the task, you will be lost in coming up with a robust HTW.

The second error is a WA made up of vague, platitudinous statements. We aspire to be a caring company. We aspire to elevate the world’s consciousness. What do those even mean? These provide little or no context for the WTP/HTW choices that follow and are unhelpful to crafting a great HTW.

With respect to WTP choices, they are unhelpful to HTW choices when they are unlinked—which is frequently the case. Far too typically, management contemplates WTP independently of HTW and picks the WTP that look most luscious—it is large, it is growing, it features high margins, etc. Unfortunately, that WTP inevitably looks luscious to many other competitors as well. Because of the intense competition for that luscious WTP, when it comes to determining a HTW for it, there simply isn’t one for the company in question. There are lots of how-to-play options available to play like one of the other enthusiastic participants—and one of these blah options becomes the misnamed “HTW.”

This sort of thing often happens with “fighting brands.” The scenario is that a differentiated player doesn’t like the incursion of an effective low-cost player into its market that creates dramatic growth in the low-price segment of its market. So, it adds this segment to its WTP. But every single time I have seen this, the HTW is really a blah how-to-play—and an unprofitable one at that.

It is harder than the other four questions

You have wide latitude of what you say on your WA. You can say practically anything. Similarly, for WTP, you can pick anything because with few exceptions, no one can stop you from playing in a place of your choosing. Must-have Capabilities (MHC) are not terribly hard to identify when you have done the first three boxes—though if you haven’t done them well, you will end up identifying MHC that you are incapable of building. And similarly, once you have identified your MHC, it isn’t terribly challenging to identify the Enabling Management Systems (EMS) that you would have to put in place to build and maintain the MHC.

But for HTW, there is a high bar. You must be superior to everyone else in your chosen WTP to have a genuine HTW. That means developing a plausible theory for how you will be competitively distinctive. How-to-play is easy because it is a low bar. HTW is hard because the definition is tighter and more challenging.

Management delusion

The fact that it is hard leads to delusion when it comes to HTW. My friend and colleague Michael Porter often remarked that the dream of many executives is to do the same as every other company but get superior results. Sadly, like Mike, I have seen this often. There is a relatively widespread belief that if a company does the same things as competitors but just tries harder, it will earn superior and attractive returns. It would be nice if that were true—but it just isn’t. The others try hard, too!

Unhelpful supporting systems

The systems outside the company that should support strong HTW choices don’t. The capital markets generally mete out greater punishments for unique choices that don’t work out well than they do for making no interesting choices whatsoever. They love blah sameness. Business schools don’t teach students how to generate creative strategy choices but rather how to analyze data as a managerial technocrat. And strategy consulting firms do very little real strategy anymore because it is a much smaller and less profitable business than overhead cost reduction, post-merger integration, and digital transformation. Net, there is very little either encouragement or support for high-quality HTW choices in strategy.

What to do about it

There are four things that you can do to improve the quality of your HTW choices.

Recognize the playing field

Internalize the reality that the supporting systems aren’t supportive. Don’t be discouraged by the reality. Recognize that the capital markets will be net negative, business schools unhelpful, and strategy consulting firms expensive and unhelpful. Recognize that you will have to build your skills with little outside help. This is the biggest reason that I write this series—to provide practical help when there is little out there to be found.

And drop the delusion. Don’t waste precious time and resources on replicating competitors and hoping for terrific results. Such results aren’t just around the corner.

Show restraint on the front end

Don’t believe that you can lock and load on your WA before proceeding to the other choices. Just develop a general idea of what kind of WA would be interesting and inspiring and then park it for further work and refinement when you have considered the other four choices.

Don’t ever make your WTP choice independently of HTW. I keep making this argument as strenuously as I can, including in this series—On the Inseparability of Where-to-Play and How-to-Win: Why Thinking about them Independently will Wreck your Strategy. The subtitle is not an exaggeration! Nonetheless, strategy teams still make lists of WTP and pick a luscious one before proceeding to HTW.

As I have written previously in this series, there is lots of strategic leverage in WTP, but only if it is paired with a great HTW with each complementing the other perfectly.

Buckle up for hard thinking

Recognize that HTW is a tough task and buckle up. It doesn’t just pop out of a slew of analyses. And it isn’t the summation of a list of consensus initiatives. It is a theory of advantage: how we are going to perform sustainably better than competitors. It isn’t easy to create a unique new theory. So, it is unlikely that you will get it on your first iteration. It will be a journey and not a quick or easy one. Remember while you are on that journey that a winding road is a feature, not a bug—that is, it is a feature of the development of a HTW worth having.

Search along multiple vectors

Don’t jump quickly onto a single HTW theory. Source theories broadly and keep multiple theories in play. I have discussed three search vectors—analogies, trade-offs and anomalies—in a previous piece in this series. Search across all three for unique HTWs. Don’t worry at all if you haven’t got lots of data early on to support your theories. You don’t want to kill possibilities early. They need to be nurtured—and stress-tested ever more intensively over time using the Strategic Choice Structuring Process (laid out in the piece).

Practitioner insights

To be a great strategist, you need to master HTW. A strategy can’t be great without a great heart of strategy—the WTP/HTW combination—and of course that pair can’t be great without a uniquely powerful and well-matched HTW. Done poorly, HTW undermines strategy—making it into a blah playing to play. And frankly, life is too short for you to waste years of your worklife playing to play.

HTW is the hardest part of strategy. Help yourself by treating it as such. Impatience isn’t helpful to you in creating a powerful HTW. Taking the necessary time is.

Don’t undermine your effort by setting the bar low to make the task easier. Set the bar high at a theory of sustainable advantage.

Go broad before narrowing. Iterate before settling. You can do this!