In early June, Dave Margulies, owner and producer of High Sierra Music Festival, was working on a printed pocket guide with a show schedule, which organizers will hand out to attendees of the more than 30-year-old Quincy, California, event.

That there even would be a festival to navigate this year wasn’t a foregone conclusion. Margulies says the festival used to sell about 7,000 tickets annually; in 2023 and 2024, it sold about 4,500 each year. “It almost sent us into bankruptcy,” he says.

Independent festivals like High Sierra have been hit particularly hard, but their main challenge—slumping ticket sales—is shared by big-name events. Coachella—which the past few years has welcomed more than 200,000 attendees over its two weekends—used to sell out in just hours. This year, resellers like StubHub had tickets available for less than face value shortly ahead of the event’s first weekend in mid-April. Recent attendance is also less than half of the number who attended the event in 2014.

For 2025, Margulies significantly changed how he curated the lineup to curb costs. He did not book high-dollar headliners like Robert Plant, Jason Isbell, and Sturgill Simpson, who all have played the festival in the past, and instead focused on smaller acts like Molly Tuttle, a Grammy-nominated bluegrass guitarist, and the up-and-coming jam band Dogs in a Pile.

Flagging ticket sales—and rising costs for artists and organizers—are putting unprecedented pressure on festivals’ bottom line. And in such a challenging environment, smaller festivals are becoming a canary in the coal mine for the larger industry. “This is really a make-or-break year,” Margulies says.

Rising prices—for everyone

In 2006 in Chicago, Mike Reed, a drummer and event producer, founded Pitchfork Music Festival with the eponymous digital music site. The initial focus was on booking such indie acts as Andrew Bird and The Decemberists.

“The landscape for festivals was really bare,” Reed says. He curated the lineup based on Pitchfork’s best new music lists, and the event grew to attract about 60,000 fans and sold out each year until 2017, when the “specialness” of the event started to wear off, Reed says.

That’s when the focus shifted to booking larger acts from more genres—including Kendrick Lamar and Chance the Rapper—moving away from just indie artists. Reed says that focus, and the accompanying cost of booking big-name artists, led Pitchfork parent Condé Nast to announce in November 2024 that it would be discontinuing the festival.

For a headliner like Lamar in 2014, organizers paid $325,000; a few years earlier, the cost of a headliner was $70,000, Reed says. Those costs for top-billed talent have only ballooned further since the pandemic, in part because of how much touring now costs for artists.

Hank Sacks, a booking agent with Partisan Arts, which works with artists like Jack Johnson, and Big Head Todd and the Monsters, says renting a tour bus now costs twice as much as it did before the pandemic. That expense then factors into artists’ appearance fees, and ticket prices. “Those costs have trickled down to the consumer,” Sacks says.

Insurance premiums also increased between 25% and 40%, depending on the event, according to Steven Perlini, president of Wise Risk, which has insured many of the largest festivals in the United States.

In 2015, a three-day general admission ticket to Coachella cost $375. This year, a ticket to the first weekend cost $649 and for the second weekend, $599.

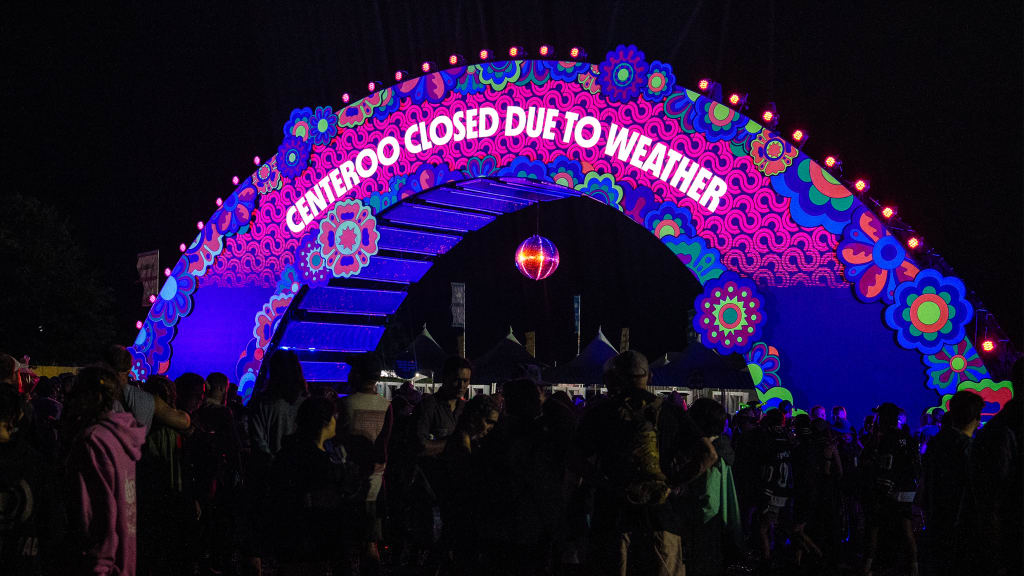

Those costs could continue to rise because of climate change, which has increased the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. This year, Bonnaroo organizers canceled the festival after one day this year because the area had received one inch of rain, and forecasts suggested ongoing precipitation would make camping—and leaving—harder if the festival kept fans around.

If scientists’ forecast proves accurate and the amount of drenching rains and wildfires increases, that would lead to higher rates, higher deductibles, and more restrictive policy conditions—and higher prices.

“If your costs are going up, the only way to make it profitable is for you to increase your revenues by charging more for tickets,” Perlini says.

Sales slump, festivals close

In 2023, there were at least 48 festival cancellations, according to Music Festival Wizard, a publication that tracks the events. The next year, there were 95 cancellations, some of them at that last minute, leaving fans angry. So far this year, there have been at least 45.

Those who still play, organize, and attend festivals say events being canceled due to low sales take away the opportunity for like-minded music fans to come together around their favorite artists.

“I’m a huge fan of making a pilgrimage to distant locales because it just changes the way that you witness the world, and that’s what the music festival is there to do,” says Grace Potter, a Grammy-nominated musicians who has played festivals of all sizes, and organizes Grand North Point festival in Vermont.

The cause is often the same—low sales making the cost of putting on an event untenable.

One bright spot has been EDM. Fueled by 6% year-over-year growth in 2024, the electronic music industry hit $12.9 billion last year, according to entertainment analysis firm Midia Research. Flagship festival Electric Daisy Belgian festival Tomorrowland sold out this year, and U.S. events Ultra and EDC regularly sell out well in advance.

But across the wider industry, Midia notes that the global music industry’s revenue growth slowed in 2024, due in part to a slowdown in ticket sales after an initial post-pandemic boom.

“Consumers have less disposable income to spend on entertainment, so it’s put the festivals under a lot of pressure,” says Vito Valentinetti, Music Festival Wizard cofounder and editor-in-chief.

Music fans’ budgets have tightened amid a 55% increase in the cost of general admission festival tickets between 2014 and 2024—an issue that’s been exacerbated by the rising cost of doing business for artists and organizers.

Whereas owners of a festival like Coachella can weather a downturn, “some of them just don’t have the money to ride it out,” says Valentinetti, of Music Festival Wizard.

Ahead of this weekend, Margulies, of High Sierra, was hopeful the event would once again sell 4,500 tickets as he spent less on artists to keep tickets at their $392 price point.

Despite telling Fast Company in early June that he had no plans to cancel the event, Margulies seemed to flirt with the idea of canceling by the middle of the month, telling a local news outlet that record-low ticket sales forced him to reconsider. The story helped sell enough tickets that he decided to continue with this year’s event.

“I’m just hoping that we can make ends meet so we get to do it again next year,” he says.