The cinematic journey in Binnigula’sa’ (Ancient Zapotec People) (2024) begins in the Mexican countryside. Modern civilization — signified by concrete, metal, and powerlines — peeks through the green landscape to reveal a more rigid world of roads, chain-link fences, and poles, the latter eventually dominating the screen. The film tells the story of the accidental discovery of the Cheguigo Monolith, an ancient stone figure, by a 14-year-old boy exploring the countryside in 1960.

Under the pretext of conducting further research, the government quickly relocated the object to the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, where it remains on display as a treasure of ancient Mexico. At the core of this thoughtful, layered story is the question: Who do museums really serve?

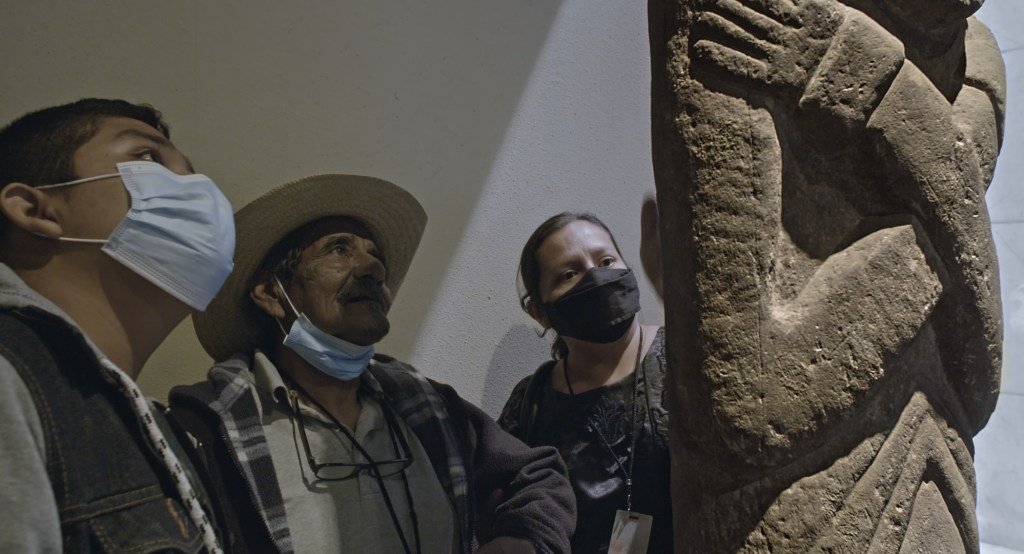

Six decades later, Ta Cándido, who made the discovery, travels to the capital with the filmmaker and friends to reconnect with the monolith. There, he expresses his desire to a local museum official to recover and return it to Oaxaca, where a small museum has already been built to house it alongside other regional archaeological artifacts. He learns that the monolith is not only unlabeled for visitors, but it also lacks the story of its discovery, further alienating those who feel a connection to it.

The official, Dr. Martha Carmona, meets with the regional visitors and responds on camera in a manner that feels cold. She corrects Cándido, stating that he did not donate the sculpture. Rather, since it was national heritage, it was a “voluntary handover,” suggesting it would’ve been illegal to do otherwise.

In that moment, you can see the metaphorical drawbridge of class in Mexico rise, leaving rural folk with Zapotec heritage empty-handed on the other side of the moat, disappointed by government trickery embodied by a Mexican official who dismisses citizens with a deep connection to the object.

Dr. Carmona adds that the monolith can’t be removed even if the museum wanted to because they have fixed it to the ground in a manner that could damage it. This raises a troubling question: Why would a museum anchor an object so securely that it can never be moved? Are they the rightful custodians of such artifacts, or merely jailers? Considering the growing chorus of voices in Mexico demanding the return of artifacts to the country, it is particularly ironic to see that regional voices are being drowned out by those in the capital, demonstrating that those dynamics are not only international but very much local.

Directed by Jorge Ángel Pérez, Binnigula’sa’ points to the living, breathing heritage of an object that continues to hold meaning for those eager to connect with the local past. It reminded me of a podcast I did years ago about a 6th or 7th-century CE Maya plate in which Popti storyteller Maria Monteja pointed out that many of the migrants crossing the Mexico/US border are often Maya themselves. This movie reinforces what many already know: museums want to acquire objects without the burden of people and their associated cultures. This dynamic is not unique to Mexico, but the film powerfully foregrounds it within the country’s own complex class and racial landscape. Although we continue to encounter the same in museums elsewhere, it’s striking to see this dynamic so starkly enforced in Mexico. In the last decade, there’s been more attention devoted to understanding the identity dynamics of Mexico, such as Alfonso Cuarón’s film Roma (2018). This full-length documentary does its part to highlight the chasm that exists between the haves and have-nots in one of the world’s most populous nations.

Watching the film, you will get a clear sense that the state wants to rob the object of its local histories and prevent it from becoming a living and breathing part of the original community, instead rendering it as an artifact that needs care, like a sickly patient. It’s a stark reminder: Sometimes the best way to kill something and rob it of its history is to place it in a museum.

Binnigula’sa’ (Ancient Zapotec People) (2024) is directed by Jorge Ángel Pérez and was screened at the Blackstar Film Festival. It is available for viewing online.