Rob Leclerc, PhD, is founding partner at AgFunder, the venture capital firm and parent company of AgFunderNews.

I’m currently reading Andrew Ross Sorkin’s new book 1929, which traces the characters at the center of the market crash that ran from 1929 to 1933 before the Great Depression. The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 89% from its peak of 381 in September 1929 to 41 in July 1932. In today’s terms, that’s like the Dow dropping back to where it was in 1996.

Sorkin draws subtle parallels to today such as tariffs under Smoot-Hawley, a long bull market, and speculative excess.

But the differences are just as important.

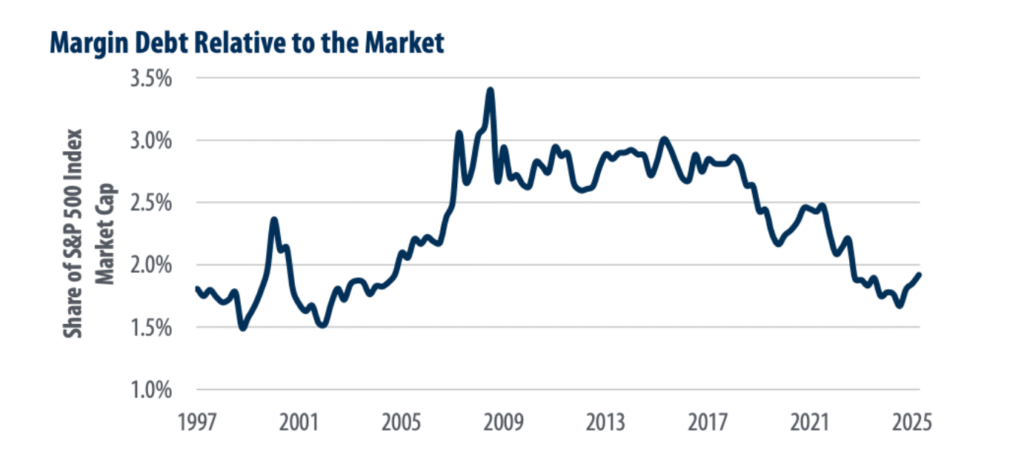

First, leverage. In 1929, margin debt reached roughly 9% of GDP, and investors could buy stocks with as little as 10–20% down. Today, margin debt is about $1 trillion, or roughly 3% of GDP, and most investors must put down 50% or more. Margin debt has risen from $700 billion a year ago, but relative to the size of the market, it’s near its lowest point since 2005.

Second, the policy response. The Federal Reserve was hands-off in the late 1920s, and President Hoover resisted intervention. There was no FDIC, so when banks started failing in 1930, deposits vanished and panic spread. The economy had begun to stabilize after the 1929 market collapse, but bank panics turned a financial crash into a decade-long depression.

Given that context, it’s unlikely that a market correction today would echo 1929’s collapse. Still, many investors are jittery about the AI boom, wondering if this ends like the railroad mania of the 1800s or the telecom bubble of the 1990s.

When the bubble pops depends on two questions:

Do we face GPU overcapacity? Probably not. We hear about overcapacity in railroads and fiber optics, but not in electrification. AI looks more like energy than transportation or communications, and the demand for intelligence is limited only by cost, not utility. Even if intelligence gains from larger models plateau, we’d transition to long runs of parallel AIs brute-forcing their way through the solutions space (the universe of possible answers the AI can search through).

Drawing on this, many are finding that it’s not intelligence AI is missing; it’s agency. I believe that agency will require significantly more compute than intelligence.

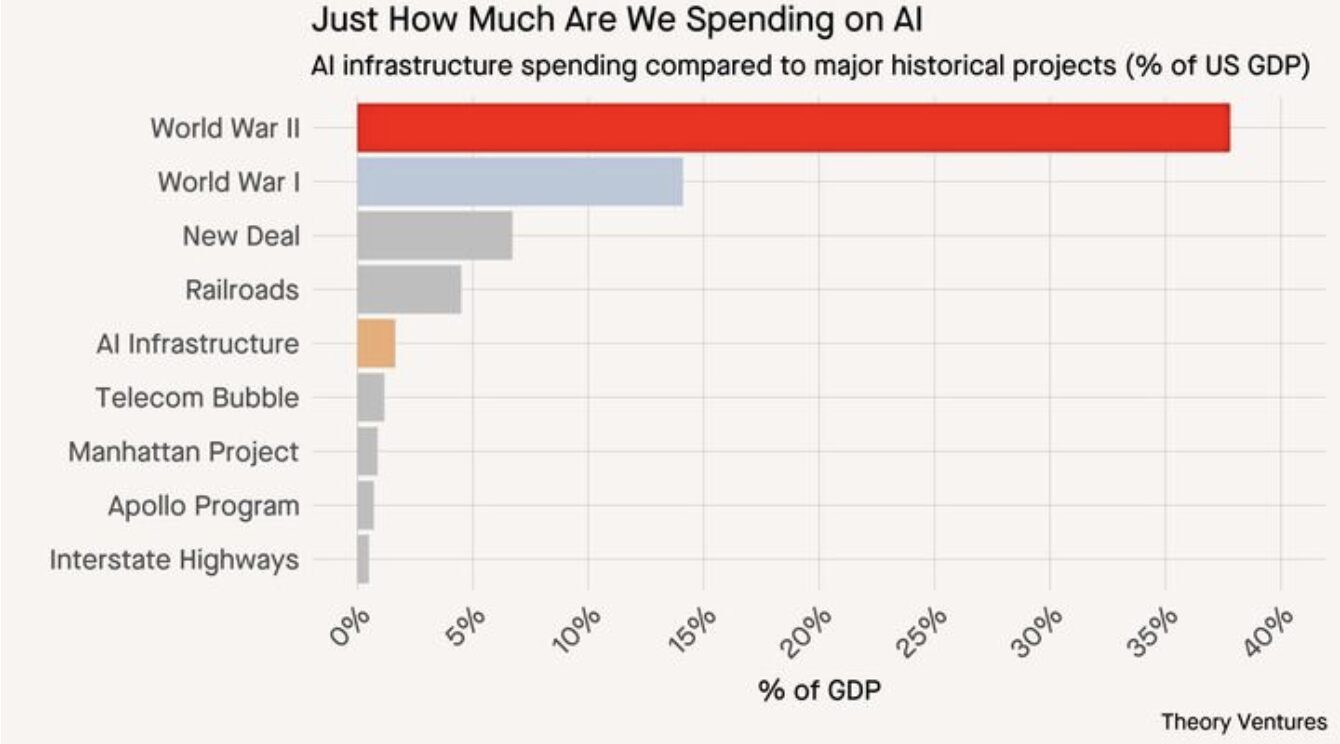

How much more capital can flow into data centers? AI infrastructure spending currently stands around 1.3% of U.S. GDP; roughly $350 billion a year. That sounds huge, but it’s small compared to other industrial buildouts. Railroads peaked at 6–7% of GDP in the late 19th century; the WWII mobilization reached over 40%; even the 1950s highway program ran 3–4%. If railroads are the benchmark for commercial endeavors, AI capex could 5x before it looks stretched.

But here’s the deeper point. This isn’t just a speculative boom chasing returns. It’s also a national-security race. The railroad and telecom expansions were driven by greed, but the AI boom is also being driven by fear. If the West loses technological leadership to China, the fallout is existential, not just financial.

The US government knows this. That’s why it’s subsidizing AI chips, restricting exports, fast-tracking grid expansions, and quietly aligning commercial compute with defense infrastructure. If it has to, it will drive rates negative to get as much capital directed to this as possible, even if it doesn’t backstop it directly.

The stakes resemble mobilization periods like the New Deal or World War II—moments when capital allocation coincided with national survival.

So yes, we’re in a boom, but nothing fundamental has really happened yet. The data center surge hasn’t gone parabolic, and when it does, it may be driven as much by policy as by profit.

The post Where are we in the AI bubble? appeared first on AgFunderNews.