When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, its soldiers didn’t just take territory — they also took thousands of children. Infants were lifted from hospitals, teenagers seized at checkpoints, orphans removed from shelters and shipped across the border to be “re-educated.”

The Kremlin called it patriotic adoption. Under international law it is something else entirely: forcible deportation — a war crime and one of the five acts that can constitute genocide.

Nearly three years later, humanitarian groups estimate that between 18,000 and 20,000 Ukrainian children remain trapped inside Russia or Russian-occupied territories. Some live in state orphanages, others with Russian foster families who have sworn to raise them as “true Russians.” A few have been sent to military training centers where they are taught to fight against the country of their birth. Many have simply vanished into Russia’s gray bureaucracy or worse, into exploitation.

At the Pentagon I helped write and manage policy for biometric and identity systems. These systems and the information sharing architecture of the federal government lets U.S. agencies find and track known terrorists and, more benignly, speed up servicemembers through TSA PreCheck.

As an Army intelligence officer who began in counterterrorism and later as a Russia analyst, I realized early in the war that Ukraine’s missing children did not have to be lost forever. The U.S. and its allies already maintain systems built to locate people who do not want to be found. Those same tools can be used to find victims of state-sponsored abduction.

Yes, Russia can give these children new names and fake passports. But if the U.S. has the proper authorities and a network of partners, we should be able to find nearly all of them. We can provide this service in almost any conflict zone at little cost by using existing information-sharing arrangements. All we need to do is choose to employ them for this humanitarian purpose.

A bipartisan bill recently passed in the Senate that would authorize U.S. law-enforcement and national-security agencies to use that biometric infrastructure to locate abducted Ukrainian children. It would allow analysts to match photos, passports and border records across databases to pinpoint where children are being held or moved. The data could feed into Interpol “yellow notices,” alerting every checkpoint across Europe and North America. It would give Ukraine a live map of where its children are and clarify the path to bring them home.

That legislation now sits in the House of Representatives. Passing it would cost comparatively little — about $15 million a year by my calculation — but its moral impact would be immense. Few investments could generate more goodwill toward the U.S. than reuniting thousands of stolen sons and daughters with their families.

Some will argue this is work for charities and non-governmental organizations, not governments. That misunderstands both the scale and intent of the crime. Russia isn’t misplacing children — it is disappearing them, rewriting their identities and placing them with new families. No volunteer organization can counter a state bent on this level of deception, and no non-governmental organization has the tools of the U.S. government and its information-sharing partners.

Others worry about expanding intelligence tools for humanitarian purposes. But this is not an expansion; it is a redeployment of an existing, governed capability against genocide. The system already operates around the clock to track terrorists and traffickers. The only question is whether we will also use it to reunite families.

The Senate has already acted. Now the House Foreign Affairs and Armed Services committees face a simple decision, whether or not we should authorize the U.S. to help locate these children and turn this information over to the Ukrainian government.

Eventually, this war will end. When it does, abducted children must not be a bargaining chip. I agree with first lady Melania Trump: Repatriation has to be a precondition for peace. The technology exists. The legal framework exists. The cost is trivial. What remains is the will to act.

Russia calls the abductions “patriotic adoption.” History will remember it as a generational crime. Congress can help end it, cheaply. Pass the bill. Turn on the system. Bring these children home.

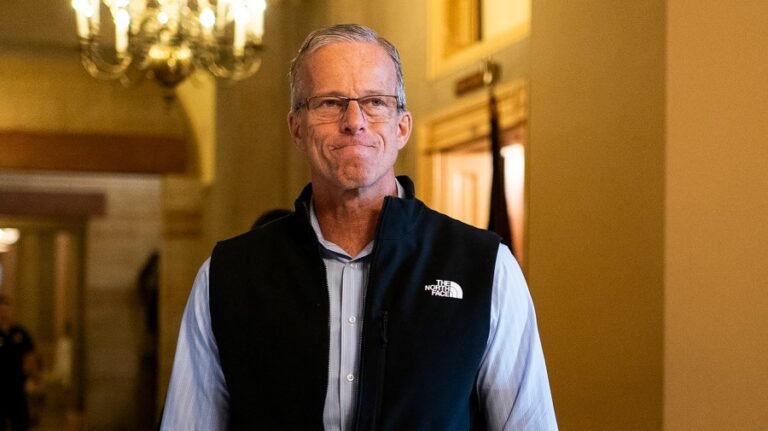

Matt Tavares is a former Pentagon official with two decades of experience in U.S. national security, now focused in the private sector on emerging technologies and the evolving nature of armed conflict.