This spring, more than 9,000 medical school graduates were left without a residency placement, a record high that exposes a deep flaw in how Washington funds physician training.

Without securing residencies, these physicians-to-be must either face a lost year and try again, take up research or administrative work, or leave medicine altogether. Meanwhile, the U.S. faces a growing physician shortage. And incredibly, federal law still restricts how many doctors can enter residency training each year.

This tragic waste of talent that could be working to serve patients is the product of government regulation and bottleneck. It is limiting the number of doctors in the U.S. at a time when huge waves of the baby boomer generation are reaching retirement, driving demand for health care services to record levels.

The government’s own Health Services and Resources Administration in a 2024 report projects the physician shortage will reach 187,000 by 2037. To improve the number of available residencies and match more doctors to the positions where they are needed, the U.S. must return the physician training process back to the supply and demand forces of the market.

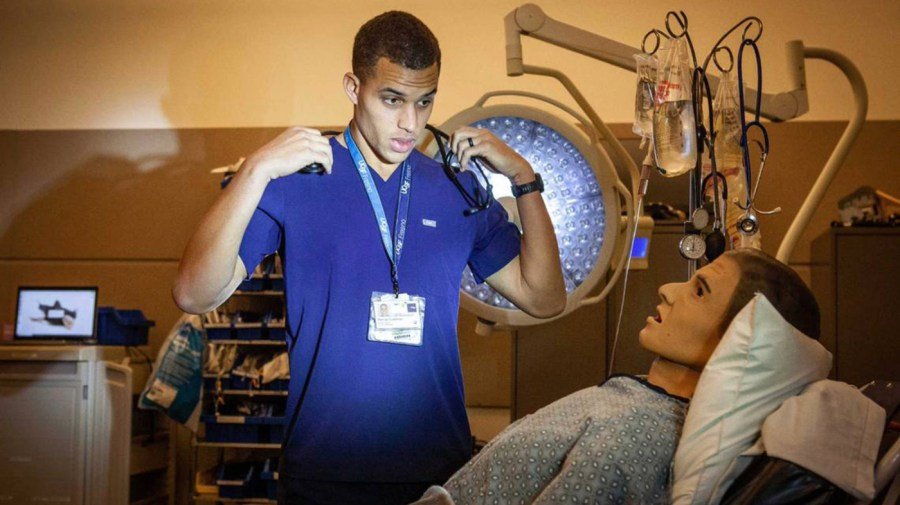

After medical school, graduates must complete a residency — a hands-on training period under supervision which is required for licensure.

So, who actually pays these resident physicians? Largely, you do, not all through your hospital bill as you might expect, but primarily through federal Medicare taxes, which subsidize graduate medical education in teaching hospitals.

In the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Congress capped the number of residency positions that Medicare would fund at each teaching hospital at 1996 levels.

The intent was to contain Medicare spending, since Graduate Medical Education is one of its major expenses. At the time, policymakers thought there might actually be a physician surplus, and in the 1990s, the American Medical Association and the Council on Graduate Medical Education predicted a doctor surplus and supported “right-sizing” the pipeline. Their position indirectly supported the residency cap. As Harvard’s Petrie-Flom Center researcher Leah Pierson has noted, the American Medical Association once lobbied to cap federal funding and cut residency positions.

Medicare through the Social Security Amendments of 1965 explicitly provided for payments to treat Medicare patients at hospitals, and additionally allowed higher payments to teaching hospitals which train physicians based on the notion that helping these teaching hospitals cover the additional costs of physician training would have a widespread societal benefit.

This arrangement of allowing the government to fund medical residencies creates a bottleneck of funding that is subject to influence by the various medical lobbies like the AMA that have historically advocated for caps and limits to the residency spots available. This has helped keep the supply of practicing doctors low, and doctors’ wages higher.

Even prestigious hospitals that can selectively choose candidates benefit from maintaining the current system because federal funding subsidizes resident salaries, keeps labor costs artificially low, and ensures a steady stream of highly skilled yet inexpensive medical labor. Expanding residency slots at these top hospitals could reduce their “prestige,” limit their ability to be as selective, and increase competition for residents, potentially driving wages higher.

Researcher and practicing physician Jeffrey Singer along with The Cato Institute write that another prominent issue is accreditation. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services only subsidizes residency programs that are accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. This limits accreditation to large hospital and medical networks, leaving out or underutilizing numerous medical institutions that could reliably train physicians such as outpatient clinics, rural health centers and private practices.

Who loses from this arrangement? Patients do. The overall outcomes of setting both supply and price caps on training physicians is that there is an ongoing shortage, which makes it more difficult for patients to find convenient and affordable medical care. This is especially prescient in rural areas which suffer from worse health outcomes and lower life expectancy due to shortages of primary care physicians in those areas.

The most effective way to solve the physician shortages and to allow the supply of doctors to flow where needed is to end Washington’s monopoly. Hospitals, states, even large charitable networks and private donors can step in to fund residency positions. Accreditation should be open to competing institutions that meet transparent quality standards rather than a single monopoly like the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education currently enforces. Clinics, rural hospitals and private practices could train far more doctors if allowed to participate and would help allocate doctors to where the shortages are.

One state offering a glimpse of what a decentralized approach can achieve is Texas, which has combined legislative action, state funding and medical school collaboration to expand residency opportunities and keep more physicians practicing in-state.

In 2017, Texas passed a law requiring all publicly funded medical schools to ensure there will be enough in-state residency positions to accommodate expected graduates. Collaborations between major medical schools in Texas who commit dollars to supporting residencies, as well as allocating state funds toward the issue, has created hundreds of additional residency positions in Texas areas hospitals.

Congress should likewise move to allow more new licensed doctors. It should phase out the Medicare residency cap created by the 1997 Balanced Budget Act and allow hospitals, states and private institutions to directly fund additional positions. States like Texas have already shown what is possible by expanding their own funding streams for residency programs.

The doctor shortage isn’t a mystery, it is a result of Washington’s outdated funding methods and its tight regulations on residency options. Lawmakers should remove these barriers and let the next generation of physicians train where they are needed most.

Matthew Blakey is a researcher and writer specializing in public policy, economics and organizational systems. His work has appeared in outlets such as the Foundation for Economic Education and RealClearMarkets.