Ever looked at the sea, the blue mixing with the orange of the sunset? Looks pretty right? But think about a flood, the sky not to be seen anymore, the sea overflowing now. Well, this story isn’t the right match for us anymore. The upper Himalayas, which are home to numerous glaciers, have now begun to recede. Such an incident is the melting of the Yala glacier. Still, why should we be concerned that it happened in Nepal, right? Let us explore the potential consequences. The glaciers can reduce the albedo effect, which is the phenomenon where they reflect sunlight. But when they melt, they absorb heat and increase the global temperature. The floods, landslides, and avalanches increase, and we lose our biodiversity in the area; all of these are the oversimplified impacts.

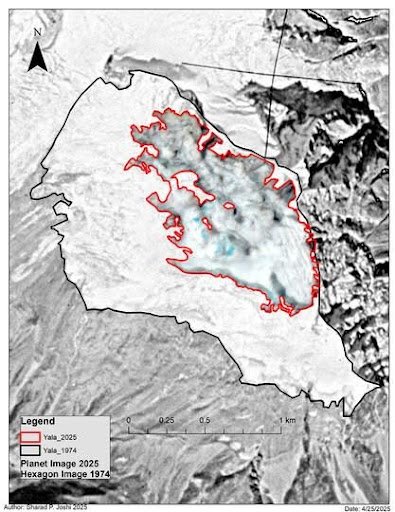

Our focus is the Yala Glacier, an extensively studied glacier in the Himalayan area. It has shrunk by 66% since the 1970s and is soon to become a “dead glacier.” This is due to the global rise in temperatures. To put it more simply, it is a positive feedback mechanism. If the global temperature increases, the glaciers melt, raising global temperatures.

Since 2011, around 100 scientists have studied the glacier under ICIMOD. Now, the Himalayan region is home to multiple glaciers. This is not just the story of the Yala glacier but many others before it, and if our actions do not align with the current climate situation, this won’t be the last glacier melting either.

This trend highlights the urgent need for climate action and adaptation measures to mitigate cascading impacts on water resources and ecosystems—Okjökull Glacier, Iceland (2019) – the world’s first glacier funeral. The Hindu Kush Himalayas, home to the largest ice mass outside the polar regions, are severely understudied despite their importance as a water source for billions. Since 1975, Earth’s mountain ranges have lost around nine trillion tonnes of ice, with many glaciers unlikely to persist past this century. Is this the story we want to write?

Slow call of disappearance

Imagine waking up every day just a little warmer than the last. Over time, your skin starts to dry, your breath gets shorter, and eventually, you begin to fade. This is what’s happening to the Yala Glacier.

The warming of the Earth, fuelled by our use of fossil fuels, urbanization and deforestation, has disrupted a centuries-long balance. Greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide, trap heat in the atmosphere, leaving Himalayan glaciers caught in the crossfire. They were formed for cold days, not the warm breath of global warming.

But it’s not just the air that’s warming up. Altering monsoon patterns yields less snow and more rain, depriving glaciers of the fresh snow they require to feed themselves. Black carbon—small dark particles from pollution—accumulates on the pure ice, trapping more heat and accelerating the melt. What used to be slow and gradual is now abrupt and alarming.

The melting of the Yala Glacier impacts the world at large—the effects can now be seen globally, to put it simply, far beyond the tops of Nepal’s mountains.

Worsening the situation, local freshwater supplies are fast becoming unreliable for communities living downstream. Glacial lakes swollen with meltwater could burst and result in GLOFs — wiping out settlements with bridges and houses in a matter of minutes. Agriculture suffers as well: the unpredictability of water sources leads to crop failures and increases food insecurity.

Aftereffects of its loss

Looking regionally, the Yala Glacier’s melt impacts the glaciers of the Hindu Kush Himalayas, which directly feed the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Indus rivers; all classed as major rivers. Substantial portions of the population rely on these rivers for sustenance, estimated at around a billion people. The glaciers become increasingly smaller in size, which, in turn, reduces river flow, especially in harsh weather. This adds unwanted strain to already decaying drinking water supplies, hydropower, as well as irrigation systems.

Now, on the global scale, losing glaciers continues to increase sea levels, leading to submerging coastlines, and exploding tidewater regions, which results in lured migrants and destruction in relation to economic stasis. Even though these shifts aren’t tremendously visible, it’s still highly concerning.

Conclusion

The Yala Glacier may be dying, but our hope doesn’t have to. We need action, not just policy meetings and pledges, but measurable changes. Governments must commit to stronger climate agreements, reduce carbon emissions, and invest in renewable energy. But it’s not only their responsibility.

We all have a role to play. The sustainable choices need to be clear as day for us, otherwise the ice of the glacier will never stop melting on our shoulders. 2025: Declared as the ‘International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation’, yet we have mourned the loss of one glacier.

Written by – Subha Nandula

Edited by – Sumedha Dhar

The post Vanishing Ice: The Tragic Retreat of Yala Glacier appeared first on The Economic Transcript.