The designers Charles and Ray Eames were two of the most important designers of the 20th century, and their legacy of innovative furniture, product, and industrial design continues to have an influence today. Now, the foundation that carries the couple’s torch is planning to open a new museum that explores their work and its enduring impact on the design world.

The Eames Institute of Infinite Curiosity just announced the purchase of a disused corporate campus in the San Francisco Bay Area that it will be converting into a large-scale art and design museum. With an adaptive reuse design by the architecture firms EHDD and Herzog & de Meuron, known for its work on the Tate Modern art museum in London and the De Young Museum in San Francisco, the new museum will focus on design through the lens of purpose. The Eames Institute expects to open the museum before 2030.

John Cary, president and CEO of the Eames Institute, says the museum is a dream project that’s finally taking form. “When we conceived of the Eames Institute seven years ago, we always wanted to create a very large, high-capacity venue for the community and the public to come and experience art and design in ways that they might not be able to otherwise,” he says.

The Eames Institute is still in the early stages of thinking through the curatorial angle for the museum, but Cary says it will be undeniably Eamesian. “We’re especially inclined toward problem-solving design, the kind of design that actually addresses a need. What we’re really interested in is trying to untangle the process from the product. That’s something that the Eameses did so well.”

Known best for iconic furniture pieces like their molded wood lounge chair and ottoman, the Eameses were multihyphenate designers who worked on projects ranging from World War II leg splints to lamps, children’s toys, and educational films. Cary says this range of output—and the emphasis on designing things people needed—makes the Eameses’ work continually relevant.

He says the new museum will celebrate this legacy of design work and house the official Eames archive, while also championing newer generations of designers and artists, as well as emerging talents. “We’re interested in really teasing out the life stories of these creatives. What were their trajectories? How did they come to be who they are?” Cary says.

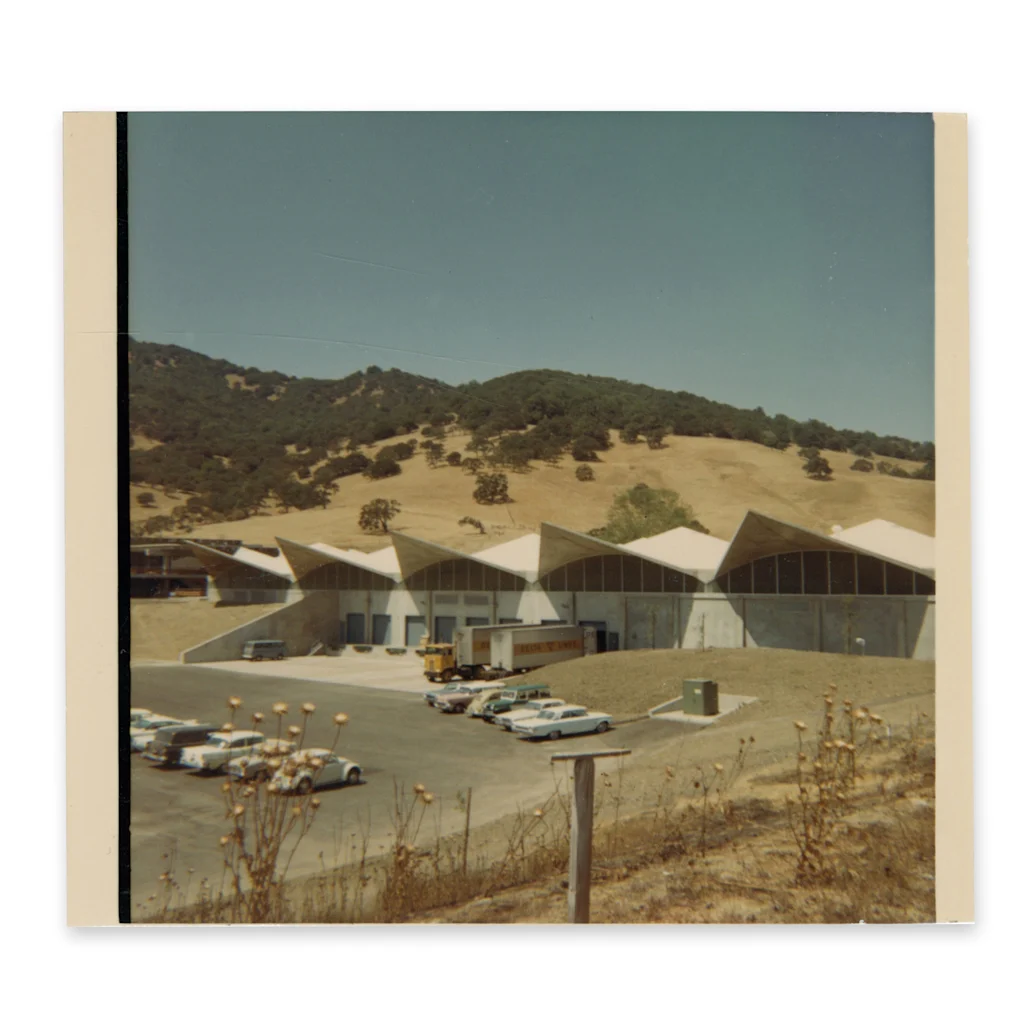

Located about 30 miles north of San Francisco in the city of Novato, the museum project is adapting a 1960s-era corporate campus and distribution center originally designed for the publisher McGraw-Hill, and used most recently by the shoemaker Birkenstock. The 88-acre campus was designed by John Savage Bolles, a modernist architect who designed San Francisco’s Candlestick Park stadium and the IBM campus in San Jose.

Despite the Novato campus being mostly a utilitarian warehouse, it jumps out from its freeway-adjacent landscape with a boldly layered shark-tooth roofline in bright white. After Birkenstock left in 2019, it sat unused.

“I fell in love with that warehouse, mostly by driving by a lot, then managing to sneak my way in. Authorized, but nonetheless, it wasn’t on the market at that point or anything,” Cary says. “I just am pretty relentless about things.”

The campus eventually went up for sale, and Cary says the Eames Institute had to beat out some stiff competition to take it over. They bought the property for $36 million and have been working with Herzog & de Meuron for the past few months to come up with conceptual designs for adapting the warehouse, an adjacent office building, and the site’s vast landscape.

Herzog & de Meuron have deep experience creating museum spaces, including the Tate Modern in London and the De Young Museum in San Francisco, and in adaptive reuse. According to Simon Demeuse, partner at Herzog & de Meuron, the firm is “deeply committed to working with existing buildings whenever possible.” Turning a former goods distribution facility into a museum offers the potential to rethink how collections are made accessible to the public, he says, via email. “The Eameses explored the world and their designs in a very open manner, leading to new ways of understanding and seeing their surroundings,” says Demeuse. “This building will allow its stewards and visitors to experience the collections and exhibits in an open manner as well, from many different perspectives and vantage points that can evolve over time.”

Despite sitting right next to Highway 101, which expands from four to six lanes across the span of the campus, berms around its edges make the property surprisingly quiet. “That kind of acoustical protection was really, really appealing,” Cary says.

It’s a bucolic condition that’s led the Eames Institute and the architects to think about the warehouse building as a kind of indoor-outdoor space. Made up of five long bays that once held canyons of pallets full of schoolbooks and, later, sandals, the warehouse’s edges could feasibly open up wide to allow programming to spill outward. Partly subterranean, the warehouse stays naturally cool, which works well for preserving artwork and archival materials, as well as for handling the region’s hot summers.

These conditions all play into the problem-solving ethos of the Eames Institute. Adapting the building to a new use instead of simply building from scratch is squarely on brand.

But Cary is cautious to note that this is not a museum about the Eameses, or at least not only that. “We’re really interested in creating a multigenerational offering for a truly multigenerational audience,” he says. “While we will always celebrate the Eameses as the seed of all of this, we have the chance to create an even bigger canvas and to bring others into it.”