LOS ANGELES — Truthfully, Nancy Buchanan: A Retrospective at the Brick, a comprehensive survey of the LA-based artist’s work, is as sprawling and diverse as the city she calls home. Buchanan studied art at the University of California, Irvine, from 1965 to 1971, along with fellow classmates (and single mothers) Barbara T. Smith and Marcia Hafif, who would become her longtime friends and collaborators. Soon, LA peers Chris Burden, Ulysses Jenkins, and Michael Zinzun, among many others, would also work with Buchanan, together helping to define the 1970s Southern California art scene. As core faculty at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) for more than 30 years, as well as a founding member of the experimental F Space Gallery, and an integral part of the Woman’s Building, Buchanan has remained deeply engaged with the city’s artistic community for more than five decades.

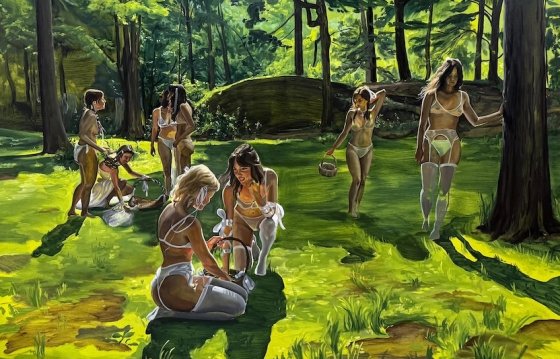

The exhibition’s curators draw from an expansive body of work spanning video, performance, drawing, painting, sculpture, collage, and installation. Each of the space’s nine galleries focuses on a theme that runs through Buchanan’s oeuvre, such as hair, interiors, and consumption. Early works reveal her eager engagement with both feminist politics and consumer culture; in the mock video advertisement “These Creatures” (1979), images of young women with ghoulishly applied makeup are paired with a male voiceover that asks “Isn’t it amazing that we allow them to live among us, these creatures that we can and do control?”

Equally unsettling are a number of pieces that deal with military intervention and weapons technology. The installations “Fallout from the Nuclear Family” (1980) and “Security” (1985) incorporate documents from Buchanan’s father’s career as a nuclear physicist and the artist’s own research into his complicated involvement in the development of atomic weapons. In the same gallery, “…And Babies?” (2003–6) presents a large glass jar, like one might see in a laboratory setting, containing a video projection of malformed fetuses and deceased babies that Buchanan witnessed in a hospital in Vietnam, preserved to document the effects of the US use of Agent Orange in that country in the 1960s. Perhaps more horrifying is that Buchanan’s work could easily be replicated to reference the birth defects caused by depleted uranium used in the US invasion of Iraq in 2004, and other untold military conflicts.

Indeed, the main takeaway from this retrospective is that the issues Buchanan began grappling with in the 1970s — misogyny, racism, the climate crisis, government secrecy, warfare, gentrification, and unbridled capitalist consumption — are not past threats but hauntingly present ones. In the video sculpture “American Dreams #7: The Price is Wrong” (1991), a miniature model of a living room, lavishly decorated with fine art paintings and gilded furnishings, holds a small television set broadcasting part of a speech by Oakland’s progressive mayor, Ron Dellums, along with attorney Mary Lee and writer Mike Davis, discussing LA’s speculative real estate market and the communities being overlooked. Nearly 30 years later, the number of California’s unhoused residents is at an all-time high. If this all feels a bit dispiriting, let hope be found in Buchanan’s artistic practice itself. Hers is an enduring legacy of creating communal strength amid forces that seek to divide.

Truthfully, Nancy Buchanan: A Retrospective continues at The Brick (518 North Western Avenue, Melrose Hill, Los Angeles) through September 20. The exhibition was curated by Laura Owens and Catherine Taft, with Hannah Burstein.