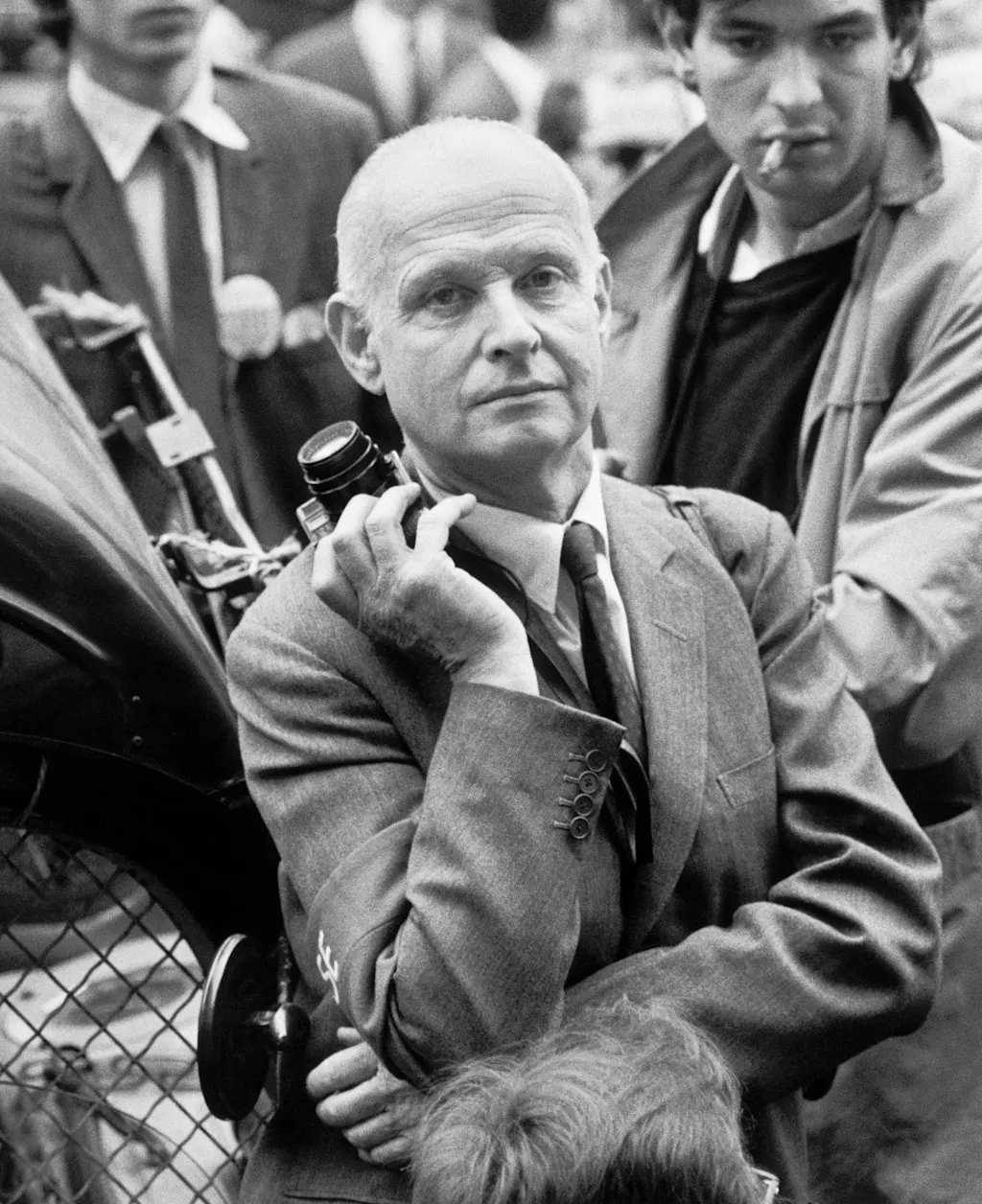

I don’t know how Henri Cartier-Bresson would have reacted to Leica replacing the optical viewfinder on his camera with an artificial display. Perhaps the French photographer and cofounder of Magnum Photos wouldn’t have cared one bit about it. Or maybe he—a profound humanist—would have disliked the idea of it almost as much as I do.

Cartier-Bresson once famously said that his Leica “became the extension of [his] eye, prowling the streets all day, feeling very strung up and ready to pounce, determined to ‘trap life’—to preserve life in the act of living.” That’s a little harder to accomplish with Leica’s new camera. Today, Leica is launching the M EV1. It’s the first M camera with a digital viewfinder, meaning the M’s most distinct asset—its beautiful optical viewfinder—is no more.

[Photo: Alain Nogues/Sygma/Sygma/Getty Images]

What is the new Leica M EV1?

Before we get to the new camera, it’s important to understand what came before. For the last seven decades, the soul of the Leica M has been its optical rangefinder viewfinder. For those not obsessed with cameras, this is a beautiful, entirely mechanical system of mirrors and prisms. When you look through it, you see the world directly, as if through a window, but with a ghostly “double image” in the center. To focus, you turn a ring on the lens, and this second image moves. When it perfectly overlaps with the main image, your subject is in focus. It’s a method that is precise, completely free of electronic lag, and creates a unique, unfiltered connection to the world.

This system, first pioneered by Leica, made the M camera the tool that defined 20th-century photojournalism. Its compact, quiet, and discreet nature allowed photographers like Robert Capa to get closer to their subjects than ever before, capturing history as it unfolded without intrusion. The M was more than a camera; it was a philosophy of seeing, demanding a manual, deliberate approach that became synonymous with the craft of photography itself.

At first glance, the M EV1 is undeniably an M. It has the same satisfying density, the same minimalist silhouette carved from magnesium and aluminum. But then you notice the changes. The front is cleaner, almost sterile, without its iconic rangefinder windows. The top plate is also different; the traditional ISO dial is gone, sacrificed to make room for the new electronic viewfinder’s housing. The camera is also noticeably lighter—46 grams less than its rangefinder cousins, a direct result of removing the complex optical and mechanical guts of the rangefinder system.

Inside, the M EV1 is built on the same foundation as the stellar M11 series. It uses the same 60-megapixel full-frame BSI CMOS sensor, a chip renowned for its incredible detail, 15 stops of dynamic range, and superb performance in low light. That sensor is paired with the company’s Maestro III processor. The company says that this combination makes the camera extremely responsive and quick. The camera also includes 64GB of internal memory, a practical feature for anyone who has ever filled a memory card at a critical moment.

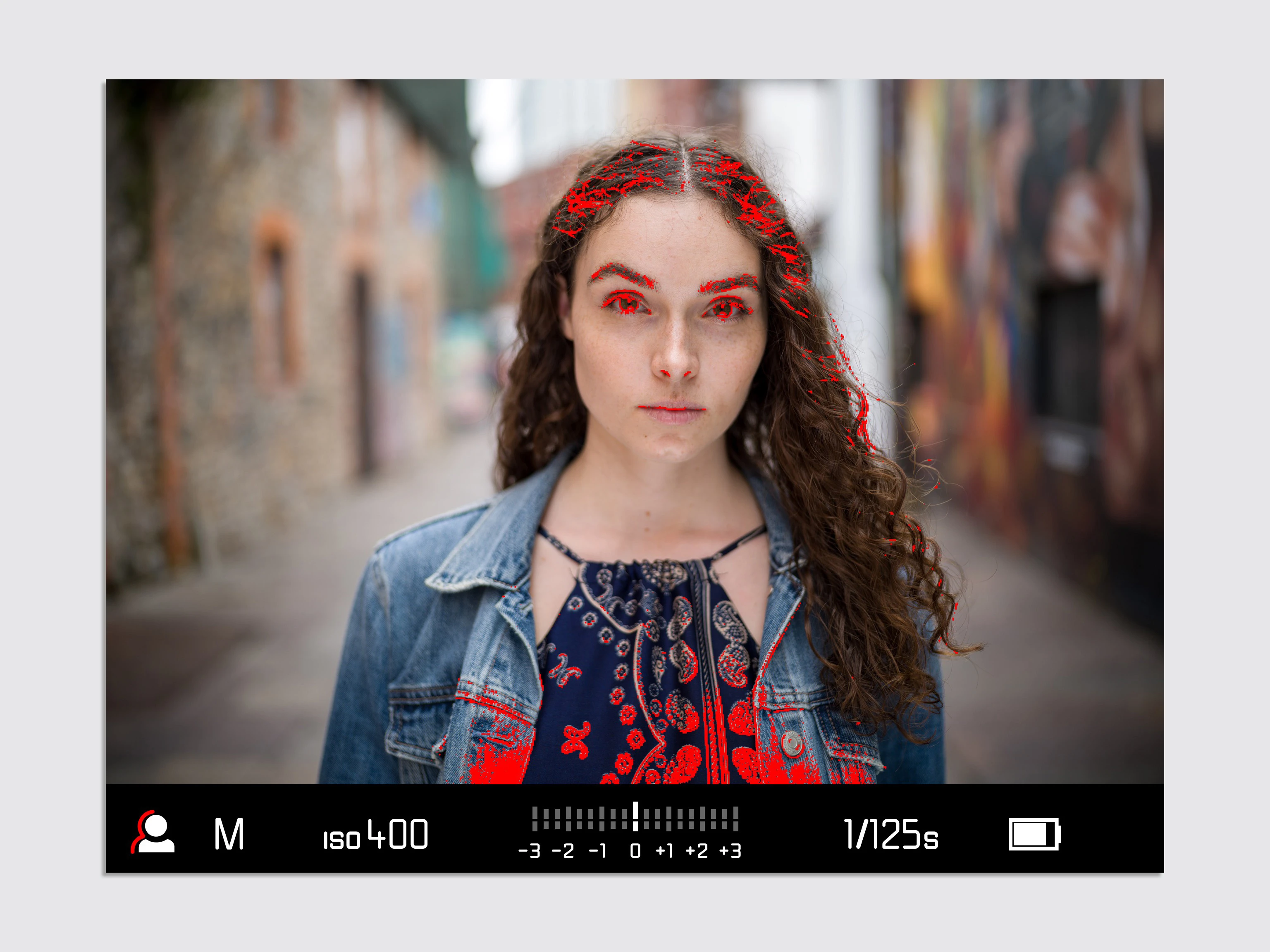

And then there’s the entire raison d’être for this camera: the electronic viewfinder (EVF). It’s a high-resolution, 5.76-million-dot screen, which, according to Leica’s claims, offers a “what you see is what you get” experience. It is, like I said, a fundamental departure from the rangefinder’s optical approximation.

The Eye of Sauron

For the first time in an M, the photographer doesn’t see real reality. It doesn’t see kids crying, running from a napalm strike in Vietnam. It doesn’t see Muhammad Ali’s fist. It doesn’t see a sailor kissing a nurse in New York’s Time Square. Or any of the photos taken with rangefinders that have arguably defined the 20th century. Út, Hoepker, or Eisenstaedt wouldn’t have seen those scenes through their own eyes but through the filter of a display that, rather than reality itself, shows a direct feed from the sensor, showing exactly how the final image will look in terms of exposure, depth of field, and color. Not the world, but the final photograph.

While showing me the new camera, Nathan Kellum-Pathe, Trade Marketing Product Communications manager at Leica USA, admitted that taking this step “was a significant topic of discussion within the company.” A decision that was ultimately justified by looking at the brand’s history and its current “strategic goals.” Read that as “sell more cameras to a new public who want an easier-to-use experience.”

He also noted that there was historical precedent, as “not every M had a rangefinder inside of it.” He believes it is a good time to do it, pointing at the 70th anniversary of the M system as the right moment to “show the market that Leica is open to changing what the M is defined by.”

This will likely rankle purists like myself (I’m writing this under embargo, so there are no public reactions at this time). Kellum-Pathe insisted that the Leica M EV1 doesn’t mean they were going to kill the traditional M. “We’ve had 70 years of the M with the rangefinder,” he says. “We will continue to have the M with the rangefinder.”

Kellum-Pathe points out that a digital viewfinder has practical advantages. It makes using wide-angle or telephoto lenses much easier, as the EVF shows the lens’s true field of view, unlike a traditional rangefinder, which is limited in its perspective. It also makes focusing with fast, shallow-depth-of-field lenses like Leica’s own Noctilux much simpler, thanks to digital tools like “focus peaking” (which highlights sharp areas in color) and magnification.

Even the frame-line selector lever on the front of the camera has been repurposed into a customizable function button to toggle these aids without taking your eye from the viewfinder. And heck, for photographers who wear glasses, a built-in diopter adjustment wheel is a nice convenience compared to the screw-on lenses required for optical viewfinders.

It’s all really cool. But it is an artificial pixel wall between a photographer’s retina and the real world. A screen is a layer of interpretation of reality, no matter how technologically good it can be. It is not a keyhole to the real world, as the optical rangefinder is. The direct human connection to the moment gets lost. In the middle of this AI clusterfrak, the last thing I need is for yet another analog instrument to become digital. But I get it. According to Kellum-Pathe, this move is a direct response to customer demand.

“The market has asked for it for quite some time,” he told me, explaining that many love the idea of the compact M body and its legendary lenses but are intimidated by the steep learning curve of the manual rangefinder system. The M EV1 is designed to be a bridge. It creates a new, third pillar in the M lineup, sitting alongside the analog and digital rangefinder models, offering an easier entry point into the Leica ecosystem, he argues.

Next Gen Leica

Priced at $8,995, the camera is also about $850 less than its rangefinder sibling, a price difference Kellum-Pathe is the result of eliminating the very object that forever defined the M: The complexity of the hand-assembled optical mechanics versus a digital panel. Much like cars getting rid of analog controls in the name of a money savings and alleged consumer demand, Leica is betting that this new model will attract a new generation of users without taking away from the purists who will always have the traditional M waiting for them. “For those who prefer the rangefinder experience, that’s never going to go away,” he insists. Well, good. I sure hope so.

And yes, of course the M EV1 will be a better camera for most people in most situations. The EVF is technically superior, more accurate, and more versatile than the 70-year-old optical rangefinder system it replaces. It makes the famously demanding process of shooting with an M camera significantly more accessible. It will probably sell like crazy (or as crazy as a $9K gadget can sell).

But again, I just can’t shake the feeling that it misses the very essence of what makes the M the M. A magic that was never about technical perfection. It was about the direct, visceral connection between the photographer’s eye and the world, viewed through a bright, clear pane of glass.

The rangefinder, with all its quirks and limitations, forces a different kind of seeing. It’s an active, mental process of aligning frames and focusing patches, a collaboration between mind and machine. It’s a peephole, not a television screen. Looking through the M EV1’s brilliant little display, as sharp and clear as it is, will always feel like watching a broadcast of reality rather than witnessing it. The digital aids, while useful, add another layer of interpretation, of noise, of things to distract you.

I think of Robert Capa on the beaches of Normandy and his vision narrowed to a small, glowing rectangle in a digital viewfinder with the chaos raging around him. And I keep coming to the idea that, while the new Leica M EV 1 is probably a perfect digital camera, while it may look and click like a regular Leica M, it will never have, by definition, the same “take a look through the magic hole and let’s see what comes at the end of this” je ne sais quoi. And for sure, it will never be the extension of Cartier-Bresson or anyone else’s eye.