The federal government is reportedly spending more than $7 million each month to pay soon-to-be-fired Education Department employees “to sit idle.” I am one of those employees.

Since mid-March, the Trump administration has blocked me and hundreds of others from doing any work while we continue to receive full pay and benefits.

In case there is any doubt, this unprecedented sidelining of civil servants is entirely against our will. We do not want to be roped into a narrative of wasteful government spending. I would like to assure readers that we Education Department staff want nothing more than to earn our paychecks by getting back to work.

Being paid to do nothing is both an inefficient use of taxpayer dollars and unlawful, but we do not sit idly. Instead, we invest our energy in telling our stories, warning the public about the consequences of closing the Education Department and fighting for our livelihoods.

Congress created the Education Department to provide crucial services, including administering billions of dollars in grants to schools and financial aid to college students, enforcing civil rights protections and publishing valuable statistics about our schools and students.

To carry out its mission, the department needs all of its more than 4,100 employees on the job. Just three months ago, the current Congress approved a budget that extended the department’s funding and current staffing levels, hardly an indication that the agency should be scrapped.

That has not stopped President Trump from trying. Earlier this spring, he and his Education Secretary, Linda McMahon, forged ahead with their explicit goal of closing the department by first slashing nearly 50 percent of the agency’s staff, despite lacking congressional authorization to do so.

Here’s what happened.

On March 11, my colleagues and I received an email from the Education Department’s human resources office stating that our positions would be eliminated as part of a force reduction. We were told we would have about eight days to close out any work before being placed on paid administrative leave.

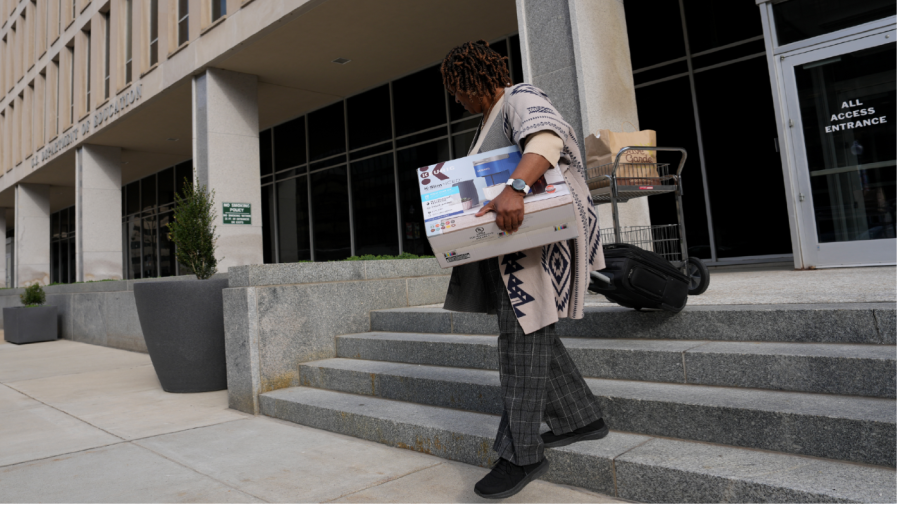

In reality, we were locked out of all systems by the next day, with access only to email for a short while longer. The agency then required most workers to return their laptops and security badges to a physical office, creating emotional scenes.

Our official notification of separation came on April 10, and for the next two months, we received little meaningful communication from our employer as we awaited our termination on June 10.

Before that could happen, the judiciary intervened. In late May, a federal judge found that the abrupt firing of half the department’s staff hobbled its ability to perform legally required functions and ordered the reinstatement of separated employees. An appeals court agreed, effectively halting the administration’s plan to terminate workers on June 10.

The administration promptly asked the Supreme Court to block the lower court rulings. Recent history suggests the Supreme Court is likely to grant that request soon, placing our jobs back on the chopping block.

Until then, we wait, hope and continue to be paid.

Education Department workers are not a drain on taxpayers. Each of us was carefully selected by agency leaders, and on day one of our service, we swore an oath to support and defend the U.S. Constitution and to faithfully serve our office’s mission.

With or without the long-overdue intervention from the courts, the administration must reverse course by reinstating federal workers. The public will find that, without delay or complaint, we will get back to work for them. Our educational institutions, teachers and students depend on it.

Bradley D. Custer is a higher education policy expert in Washington, D.C.