New Yorker staff writer and author Evan Osnos spent decades chronicling the social, economic, and political changes in China and currently writes about American politics. To understand the second election of President Trump, though, he realized he needed to understand the vast inequality in American society. According to 2024 data from the Federal Reserve, more than two-thirds of the country’s wealth is held by the top 10% of U.S. households. And the top 1% of U.S. households hold more than one-third of the country’s wealth.

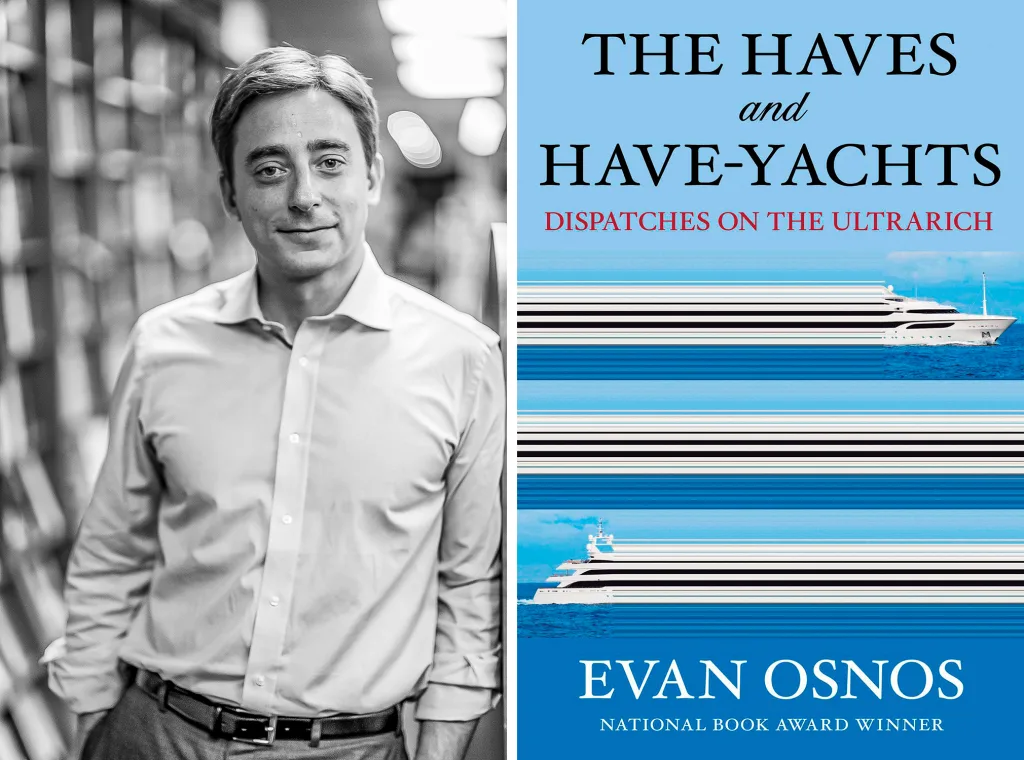

Osnos’s new collection of essays, The Haves and Have Yachts: Dispatches on the Ultrarich, explores the world of the 1%, from their tax-dodging and yacht-buying techniques to their propensity for building luxury bunkers and employing pop stars to perform at private events. Osnos came on the Most Innovative Companies podcast to talk about his book, what’s behind the rising inequality in America, and the danger that inequality poses to democracy.

Why did you want to write about the ultrarich?

In 2016 when Donald Trump was elected president, I realized that the normal tools of political analysis—the way that I usually write about what’s happening in the world—were not going to suffice. I couldn’t understand how a guy who declared himself the enemy of the elites could somehow inhabit that role while being the billionaire son of a real estate family in New York. I needed to understand. The answer to that lay, ultimately, in trying to understand the mechanics of the big money world. That was the origins of this.

You begin the book by talking about how ubiquitous the ultra wealthy are in the administration and you write that inequality has led to the undoing of many societies. Do you think that is happening in America?

We are at a very tenuous moment, and I don’t think I’m unique in that impression. All of us, no matter where we sit on the political spectrum, we look at it and say, this feels really fragile and it feels volatile. The question of course is, why? From my perspective, you can’t understand this period without recognizing that we’re living at a time of really historic, arguably unprecedented inequality in this country. That’s not an abstraction. The richest people in America have a larger share of the nation’s wealth than their predecessors did in the Gilded Age. If you want to really have an honest conversation about what it will take to hold this country together, we have to be honest about the facts. Let’s remind ourselves [that] we’ve been through these moments before and we’ve found our way back to a more stable, productive, democratic future.

The first essay is a piece about yachts. What attracted you to the topic, which also provides the title for your collection?

The super yacht is the super symbol of our era. There used to be 10 of the largest yachts [available] a generation ago, and now there are 170. They occupy this kind of strange place in our culture. They’re both visible and invisible. I mean, you see them in the New York Post or in the Daily Mail. They’re designed to stay out of reach, but they are the most conspicuous machines that anybody could possibly own.

The yachts are a symbol of a world in which capital is more mobile and more fluid and in which borders are liquified. I had this really interesting interview with a guy who has been in the yachting world for decades. He watched it turn into this ginormous industry with huge amounts of money on the line. And he said every decade or two [the yacht buyers are coming from] a new industry. First it was the Greek shipping fortunes. And so you saw Aristotle Onassis competing against another shipping magnate [for the most ostentatious yacht]. [Then] it was the oil money. All of a sudden, it was people from Saudi Arabia and the Emirates, and they had different needs. They were sailing their yachts around the Arabian Peninsula and they were inside all the time. They needed good air-conditioning. But what’s really interesting about [yacht buying] is that it tells you something about the global economy. Where is the center of gravity at any moment in our time? You could chart the history of American economics over the last 60 years by looking at the high seas.

They also depreciate in value immediately.

I remember the Financial Times wrote a great piece that described them as about as financially prudent as buying 10 Van Goghs and then holding them above your head while you’re treading water. [Yachts are] essentially something for people who have limitless resources.

You write about how it’s almost easier for a billionaire to live on a luxurious yacht than on land. It might seem uncouth to show how rich you are on land; on water, it’s a different story.

A Silicon Valley CEO said to me that the honest fact is that you can’t live in a $500 million house because the optics are weird. Your employees will be enraged at you. But a half billion dollar boat is pretty nice. This same CEO said to me that the yacht is the best place to, as he put it, absorb excess capital. A certain number of businesses have generated so much [money] because of the ownership structure for their founders and for key investors that [these people] are quite literally encountering this problem of having excess capital and having to figure out ways to park it in places that won’t cause blowback socially and culturally and ultimately in business terms.

One of the themes that I noticed across this world was that, in a way, this is the natural result of an unthinking cult of scale. It’s not that long ago that we thought scale was an unambiguous good. When I wrote a profile of Mark Zuckerberg a few years ago [for The New Yorker], I was talking to him and to his employees about this period when essentially connecting people was a euphemism for growing. And growing was a self-justifying, self-fulfilling idea. It was an end in itself. The yachts are the symbolic representation of that concept.

You grew up in Greenwich, Connecticut, and decided to write about the town’s turn towards Trump. Why did you want to write about it?

It’s always been a prosperous place. It was an amazing place to grow up as a kid. It has the only public high school that I know of that has an electron microscope. There was also a point at which I became aware that Greenwich told us something important about what was happening in Republican politics. Greenwich had been traditionally the birthplace of the country club Republican. The Bush family was from there. Prescott Bush, who was the father of George H.W. Bush, was quite literally the country club golf champion in town. He was the senator from Connecticut, and he was an old-school moderate Republican—what they used to call a Rockefeller Republican.

But in 2016, the Republican Town Committee in Greenwich was led by somebody who came out and said they were not going to vote for Jeb Bush. They were going to vote for Donald Trump. That became a revealing indicator: Republican strongholds that we might’ve thought of being more inclined towards moderate Republicans were lining up with Trump. Part of the explanation is that there had been a decision along the way that we can no longer afford to do the kind of moderate Republican thing that gives a little here and takes a little here, but ultimately believes in working with Democrats. There was an argument to be made that there was a similar thing going on in the Democratic side, in terms of getting more and more extreme. But it was when you had the birthplace of Country Club Republicanism begin to line up with Donald Trump, I said, I’ve got to understand how that happened. And this essay tells that story.

What did you learn about how American elites paved the way for Trump’s election?

There is a lot of blame to go around for creating the myth of Donald Trump that continued for so long. Around New York City, Donald Trump was a permanent piece of media furniture. He was in the papers all the time, partly because he was pretending to be his own publicist and planting stories. To see him, through The Apprentice, become something else in the eyes of Americans more broadly was a turning point. All of a sudden he [became] known, through the power of this invented persona, as the icon of a big city, successful capitalist.

Part of the reason why I think why the word elite has become so fraught is that Trump used his own position in communities of power to say to the American public, “Because I am an elite, I can help you pick the lock. I will help you understand why [the government] is corrupt, how it works, and therefore I, dear voter, will give you a piece of the action.” After a half a century of him selling the illusion of access to power and fortune, he and his family have now realized that in 2025 the thing people will pay most exorbitantly for is access to the highest reaches of the United States government. His son has created a club called Executive Branch with an initiation fee of up to $500,000.

It’s funny because at the same time, he hired a lot of elites to his cabinet.

He named 13 billionaires to the highest ranks of his administration. You can imagine a scenario in which you say, look, these are people who have succeeded. They understand the market; they understand economics. What becomes a problem is when the administration is so secluded from the experience of regular life that it has a very hard time expressing and enacting the public will.

It was quite telling when Howard Lutnick, Secretary of Commerce, said that his mother-in-law wouldn’t notice if her social security check didn’t show up. I think there’s a lot of Americans that probably would notice if their social security check didn’t show up. I think this is part of what Elon Musk ran into, when he started talking about empathy as a weakness of Western civilization or social security as a Ponzi scheme. It was a revealing indicator of how much his life had become divorced from the experience of ordinary people.

You’ve written about elites deriding other elites and saying, “I’m different because I understand the common man.” Why do you think that is so resonant with voters?

Americans at their core want to get rich. We always have and we always will. That is baked into the American idea. What’s happening now is that people in larger numbers are beginning to realize that there are impediments to that process. Part of the reason why Donald Trump was able to win again was that he is able to say to people, even in an unspoken way, that he wants them to prosper and succeed. Part of the process of getting people to understand [our level of inequality] is getting [them to] visualize some of the fault lines in our economy that are making it harder for people to prosper. The key is not saying to people they should give up on the goal of getting rich. The key is giving people the information to understand why they’re not.

When you’re talking about the sort of elites who have yachts, are they completely divorced from understanding the common person?

I think that the experience of entering into that world is actually farther away from regular life than outsiders imagine. There was a yacht owner who said on a documentary that if the public ever knew what it’s really like on these yachts, they’d bring back the guillotine. It sounds like a joke except that part of what’s happening is that [elites] are aware.

There was a really prophetic comment a century ago from [Supreme Court justice] Louis Brandeis. He said, you can either have democracy or you can have money concentrated in the hands of a small number of people, but you can’t have both. That was one of the observations that led to the New Deal and to an effort to try to shift the balance from a concentration of resources into the hands of too few, into a more equitable distribution. [That] led to what was ultimately a period of rising standards of living for more people. That period came to an end in the late 1970s. I think there is a recognition on the part of some in politics that we need to figure out a way to get back to that.

What was your favorite essay to write in the book?

The piece about pop stars performing at private parties. I embedded with Flo Rida for a bar mitzvah. It was an experience that as you’re doing it, you say to yourself, I think I will be able to die happy when I’ve done this. The reason I got interested in it was [wondering], what are the economics of that? What makes a pop star who could be performing in front of 40,000 screaming fans say, Actually I’m going to go to a sweet 16 in Teaneck. In the end, it’s not that complicated what motivates them to go. The reason why this is an artifact of our time, why it’s like a new thing, is the simple fact that, until recently, people couldn’t afford to have the Foo Fighters in their backyard on a Thursday, and now they can. I sometimes feel like I’m like a historian writing in real time about a world that we need to describe while it exists.

In 2015, Uber famously offered Beyoncé $6 million to perform at one of their corporate events. Instead, she requested an equity stake in the company and ultimately made $300 million from it.

If you step back, what’s fascinating about that is that right there is a transaction between billionaire and billionaire. When you can get on board a certain kind of opportunity and experience, then the curve goes vertical, and you get access to all kinds of other things. It can be quite dangerous for a country because it means that those people are then getting further and further from the experience of everybody else.

I think it’s perilous for those individuals because they run the risk of suddenly encountering a kind of backlash and realizing they’ve lost touch with the people they were supposed to be in touch with. I quoted Ramsay MacMullen, the great scholar of Rome, in the book. He was once asked if he could summarize the epic history of the fall of Rome as concisely as possible. He said that it took 500 years but it can be distilled into three words: fewer had more.