LONDON — How does any great creative work by a novelist or poet come into being? This question never fails to fascinate. Henry James preceded his great 1916 novel The Ambassadors by writing the most intricate of plot lines, a work almost as dense as the finished novel itself. It was quite different for the poet W.B. Yeats: The first draft of the first poem of a great sequence called The Tower was so far from its final outcome that you could never have guessed at it. And yet he got there in the end.

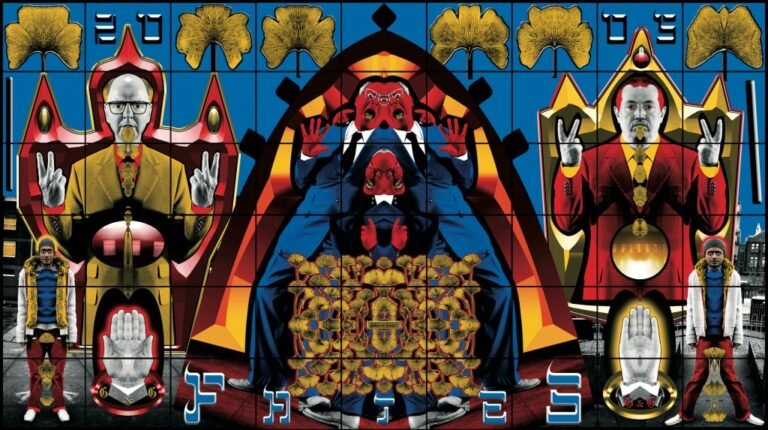

And what of Ursula K. Le Guin, the American novelist, whose many works occupied a fascinating terrain somewhere between fantasy and science fiction? How did she begin to realize her multiple fictional creations? A new exhibition at the handsomely sited Architectural Association in London — in a Georgian building that looks out onto London’s sole surviving entire 18th-century square — shows us. The Word for World is a rhythmical presentation of slender, wafty banners suspended from the ceiling, all blue cyanotypes on which are maps reproduced in white. Navigating the space is a matter of ducking and weaving.

Yes, Le Guin was a map maker. That’s how she found her way into her invented worlds. After she made her maps, she proceeded to settle on them and mentally walk around inside them. If we home in on the exhibition’s maps themselves we can begin to unlock her secrets. Take, for example, “Earthsea,” an aerial view of a great archipelago of islands, several of the larger ones in a great central cluster, others frittering out in all directions of the compass. A close look at all the hand-drawn map’s detail reveals a great deal of naming of particular locations: Havnor, Osskill Sea, the Inmost Sea, mountains, a small group of islands collectively known as The Torikles. It was her way into the imaginative world that would eventually end in a celebrated trilogy of novels. How did it help her? How did it show her the way ahead as a conjurer of a world that had never before existed?

The map was reproduced in the first edition of A Wizard of Earthsea (1968). Years later she explained in an introduction to the collected Books of Earthsea:

The first thing I did was sit down and draw a map. I saw and named Earthsea and all its islands. I knew almost nothing about them, but I knew their names. In the name is the magic.

The naming was the key — it lit the touch paper. It enabled her to “set sail with [the wizard] Ged from Gont … to Rake, and the Ninety Isles, and Osskil, and farther east even than Astowell ….”

The Word for World: The Maps of Ursula K. Le Guin continues at the Architectural Association School of Architecture (36 Bedford Square, London, England) through December 6. The exhibition was curated by Sarah Shin and designed by Standard Deviation, with consulting curator Theo Downes-Le Guin and the Ursula K Le Guin Foundation.