The Supreme Court’s conservative majority expressed doubts at oral arguments Monday about a Rastafarian man’s attempt to seek damages from prison guards who shaved his dreadlocks in violation of his religious rights.

Damon Landor was weeks away from completing his five-month sentence on a drug charge when he was transferred to a new facility. Guards handcuffed Landor to a chair and forcibly shaved his hair, court filings show.

Landor follows the Nazirite vow, which forbids him from cutting his hair. He handed guards an appeals court ruling that shaving Rastafarian inmates’ dreadlocks violates a federal religious liberty law, but guards threw it in the trash and shaved him anyway.

All sides involved condemn the man’s treatment, but at issue before the Supreme Court is whether he is entitled to seek damages from prison officials in their personal capacity. Landor’s bid to do so is backed by the Trump administration.

The Supreme Court’s 6-3 conservative majority regularly fortifies religious rights, but the justices have also been wary of expanding government officials’ exposure to damages in their individual capacities.

“It didn’t do that,” Justice Neil Gorsuch said of the statute at the center of the case. “It could do that, but it didn’t do that.”

The court is weighing the scope of the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, which strengthens religious protections for state inmates in federally funded prisons.

Five years ago, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the law’s sister statute permits money damage claims against federal officials in their individual capacities, siding with a group of practicing Muslims who alleged federal agents placed them on the No Fly List as retaliation for refusing to act as informants against their religious communities.

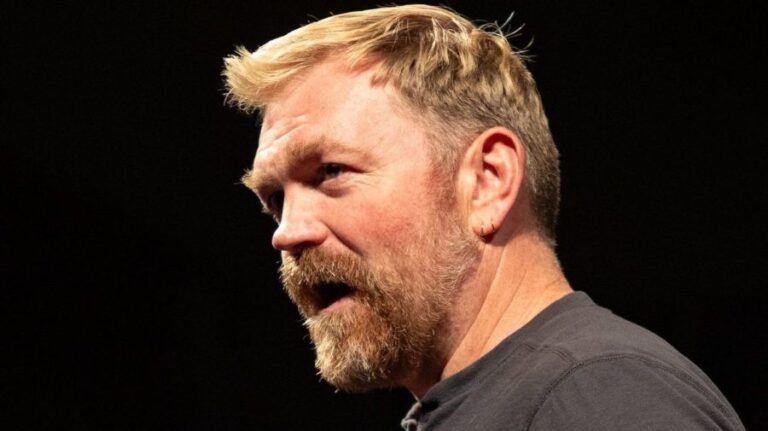

Landor, who attended Monday’s argument, says his case should follow suit.

“They’re like twins separated at birth. They clearly mean the same thing,” Zachary Tripp, Landor’s attorney, said of the two laws.

But the one now at issue before the high court has a different constitutional foundation. It was enacted as part of Congress’s spending power, and the Supreme Court has held such laws must clearly provide for damages.

“The hard part, as I see it for your case, for me, is that you need a clear statement,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh told Landor’s attorney. “And ‘appropriate relief,’ it’s not as clear as it could be in encompassing damages.”

Also bolstering the prison officials’ defense is the fact that every lower federal appeals court to decide the issue has agreed the statute doesn’t authorize damages.

“It’s so obvious that every single circuit to look at the question went the other way?” said Justice Amy Coney Barrett.

Even as the former inmate received skepticism from the court’s conservatives, the Supreme Court’s liberal justices appeared more sympathetic to his position.

“A new road by us would be to rule for respondent, correct?” asked Justice Sonia Sotomayor, referring to the prison officials.

Louisiana Solicitor General Ben Aguiñaga told the justices accepting Landor’s argument would “radically expand congressional power.”

He said Louisiana essentially entered a contract in which federal funding is conditioned on its promise to follow the law’s religious liberty protections, and the guards aren’t parties to that contract.

“Even if Congress spoke with unmistakable clarity and created such a cause of action, Congress exceeded its constitutional authority,” Aguiñaga said.

It marks the second time this term that Louisiana has appeared in front of the justices. The justices considered the state’s congressional map that added a second majority-Black district last month, when Aguiñaga urged the court to limit the use of race in redistricting.

Decisions in both cases are expected by next summer.