Want more housing market stories from Lance Lambert’s ResiClub in your inbox? Subscribe to the ResiClub newsletter.

In a “normal” housing market environment, giant homebuilder PulteGroup—which is worth $23 billion—spends $18,000 to $21,000 on incentives on a $600,000 home sale. But with affordability strained and housing market softness spreading, the homebuilding giant is now shelling out closer to $52,200 per sale of a home of that value.

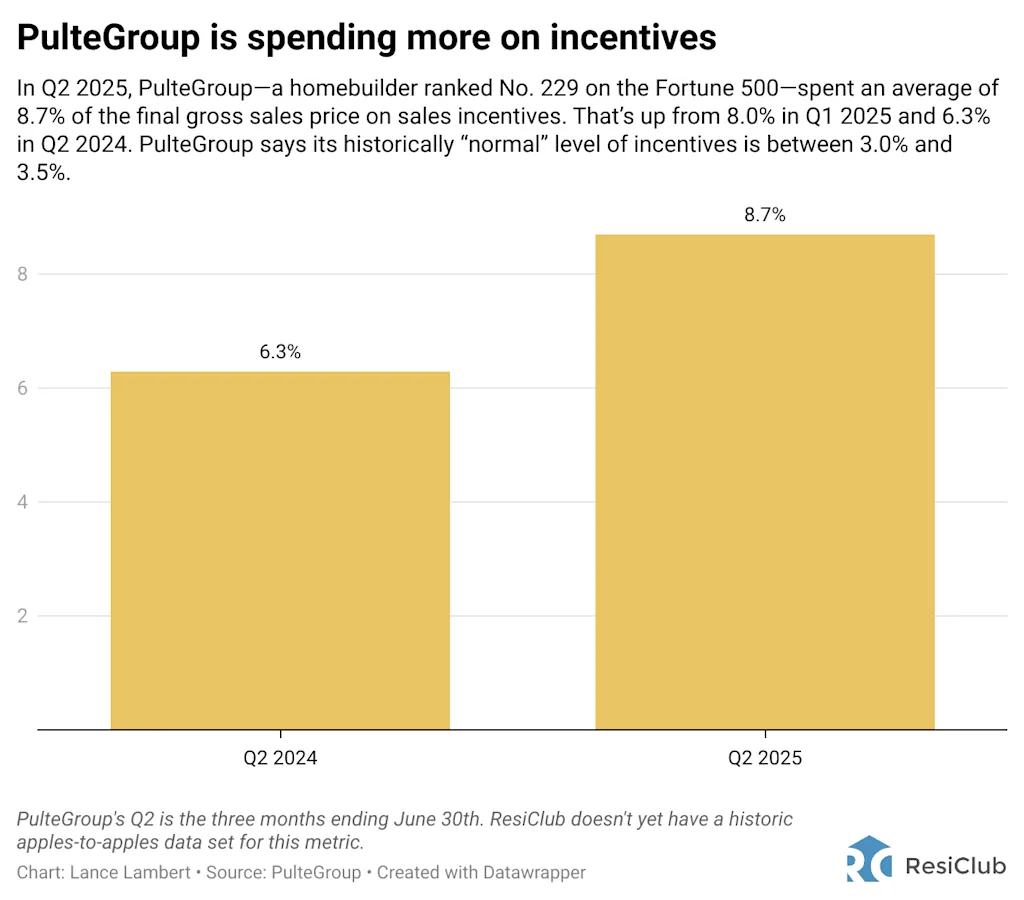

“Incentives for the second quarter were 8.7% of gross sales price, which is up from 6.3% last year, and on a sequential basis [quarter-over-quarter] up from 8.0%,” Jim Ossowski, CFO of PulteGroup, said during the builder’s July 22 earnings call.

Ever since mortgage rates spiked in mid-2022, which followed a historic run-up in U.S. home prices during the Pandemic Housing Boom, U.S. housing affordability has been strained. In housing markets where that affordability strain has manifested into spiked active inventory/months of supply and soft/falling home prices, giant homebuilders have leaned into doing bigger incentives, in particular, mortgage rate buydowns to pull in priced-out homebuyers and keep sales going.

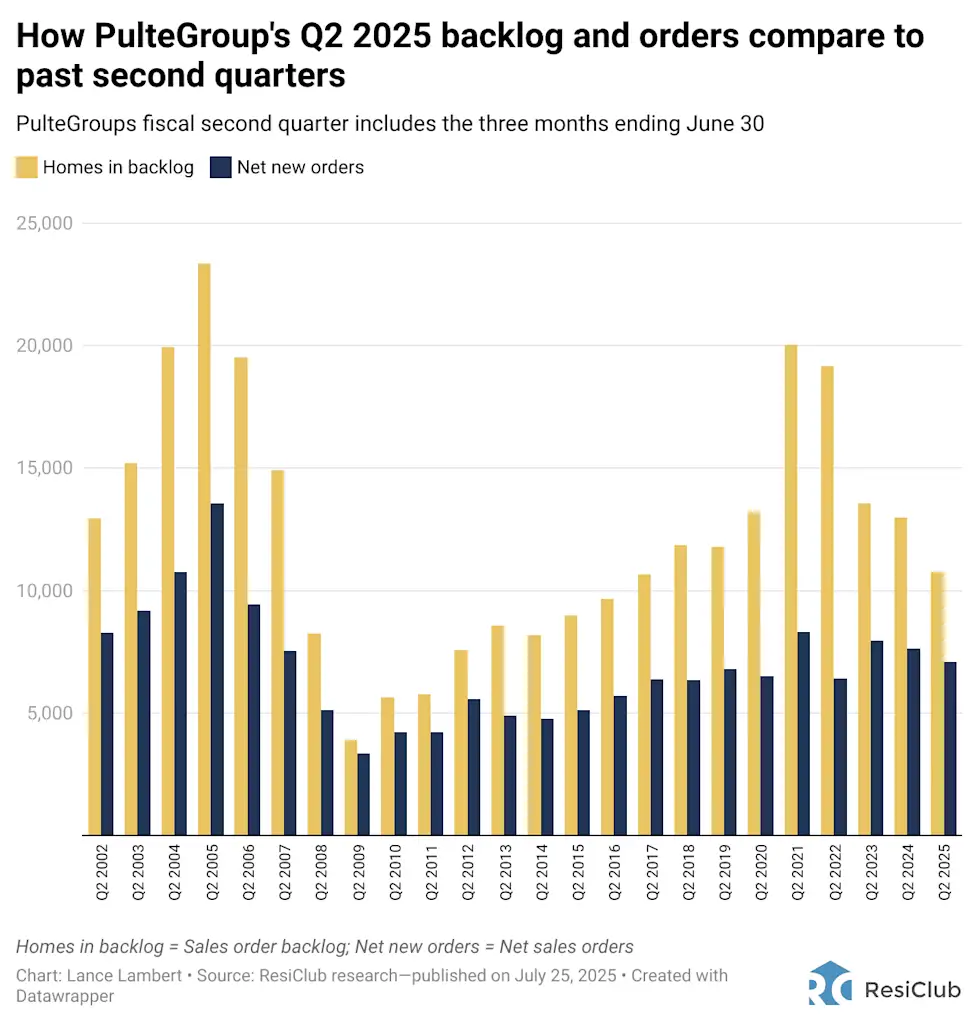

Of course, given the widespread housing market softening—most acute over the past year in parts of the West, Southwest, and Southeast—many homebuilders, including PulteGroup, have further increased their incentive spending to prevent a deeper pullback in home sales.

“We have responded to these conditions by adjusting [net] sales prices where necessary and focusing sales incentives on closing cost incentives, especially mortgage interest rate buydowns,” wrote PulteGroup in its earnings report published on July 22.

That strategy has led to some additional builder gross-profit compression.

PulteGroup’s gross margin in Q2 2025 still came in at 27.0%. While that’s down from the cycle high of 31.3% at the end of the Pandemic Housing Boom in Q2 2022, it remains above pre-pandemic levels seen in Q2 2018 (24.0%) and Q2 2019 (23.1%). (Some builders, like Lennar, have seen greater margin compression.)

Are bigger incentives essentially falling home prices?

Sometimes, yes. Sometimes, no.

In some cases, increased incentive spending is effectively a price cut—just delivered in a less visible way. But not always. Since 2022, part of the rise in incentive spending in some markets has come from homebuilders increasing base home prices and then using some of that additional revenue to fund incentives.

That said, based on PulteGroup’s own commentary and the visible margin compression, it’s clear that in at least some markets, its increased incentive spending is functioning as a net effective price cut.

Instead of bigger incentives, why don’t homebuilders like PulteGroup just do bigger outright home price cuts?

Some homebuilders prefer offering larger incentives rather than outright price cuts to protect community comps. Outright price cuts can sometimes complicate future sales and upset homebuyers currently in the backlog.

Another reason more homebuilders are leaning into bigger incentives is because large builders claim there’s currently arbitrage in financial markets, where every $1 spent on a mortgage rate buydown delivers a greater monthly payment reduction for the buyer than a $1 home price cut.

“The focus still has been on rates and rate buydowns [rather than outright price cuts] and keeping consistency of that. And if we see a little weakness in a market or buy community, we may adjust further down, but [it’s] still more advantageous to the buyer and the cost is less to increase the rate buy down than to cut the price,” D.R. Horton CEO Paul Romanowski told investors in April.

Why does $1 spent on mortgage rate buydowns by builders create more payment savings right now than a $1 price cut?

The answer is a little wonky.

Here’s the in-depth breakdown by housing analyst Kevin Erdmann—who is the author of the Erdmann Housing Tracker.

As Erdmann explains to ResiClub:

“One reason that mortgage rates are higher than treasuries is that they have prepayment risk. If interest rates go up, the investors are stuck with fixed income that is lower than the new market rate. If interest rates go down, the borrowers refinance and the investors don’t get the extra income from the higher fixed rates. So they charge an extra spread for prepayment risk. When short term rates are higher than [long-term rates], like they are now, the prepayment spread is higher because they expect mortgage rates to drop at some point in the future and the borrowers to refinance. If the builders arrange the terms so that the buyers are paying [a] 4% or 5% [mortgage rate] out of the gate, they [the borrower] aren’t going to prepay [because they’re less likely to refi] and so the prepayment spread is very low. From the borrowers perspective, the rate buydown only pays off slowly over time as you make the payments based on the low rate. They are incentivized not to refinance, sell the home, or pay the loan off early, so the expected duration of the mortgages is much longer. The builder and borrower can pocket the gains from the lower prepayment spread.”

What risks do builder buydowns pose to homebuyers?

While mortgage rate buydowns can offer meaningful monthly payment relief, they could also come with trade-offs. If a buyer accepts a builder buydown instead of negotiating a lower sale price, they may be locking in a deal (depending on the terms) that only pays off if mortgage rates stay elevated. Should rates fall soon after closing, that buyer may find themselves unable to benefit fully from refinancing. In that scenario, a lower sale price or another form of incentive might have offered more long-term value.

Another risk is overpaying for the buydown. If a buyer stretches their budget or accepts a higher purchase price to secure the incentive, they could be more vulnerable to ending up underwater—owing more than the home is worth—if local home prices decline and they need to sell within a few years.

Speaking to analysts last month, KB Home—which tends to favor direct price reductions over incentives when affordability adjustments are needed—indeed warned that some buyers opting for competitors’ rate buydown deals may be overpaying for new homes. If those buyers need to sell soon, they could struggle to recoup the inflated base price tied to the incentive-heavy purchase.

“I believe that there are customers [of other homebuilders] that are overpaying for the home to effectively get an incentive. So they’re tied into this higher price that they’re gonna be stuck with forever until they sell that home. They may potentially be upside down when they try to sell that home versus a clean, simple, transparent way of selling—the value of what we offer,” KB Home COO Rob McGibney said on the company’s June earnings call.

Builder buydowns have lost a little of their magic lately

Over the past year, many public homebuilders have seen mortgage rate buydowns lose some of their magic—at least compared to early 2023, when buydowns played a key role in firming up new construction sales.

“I think the commentary that you’ve heard from us is that there’s actually inelasticity in, you know, pricing. And that more incentives don’t necessarily translate into incremental volume. So we’re trying to get incentives, you know, to the level where we get the appropriate level of volume. But pouring more incentives on top of that doesn’t necessarily translate into the incremental volume that would justify those incentives. So, you know, that’s why we’ve tried to continue to maintain some discipline around what we’re doing on the incentive load,” Ryan Marshall, CEO of PulteGroup, said during the builder’s July 22 earnings call.

Marshall added: “We think the opportunity is to bring incentives lower over time. We’re clearly not there right now, but, you know, I would long for the days of, you know, more normal incentive loads of 3.0% to 3.5%.”

Note: Net of incentives, PulteGroup’s average sale price was $559,000 in Q2 2025—which is why we used $600,000 in the hypothetical example in the article’s intro.