‣ Aphantasia, or the inability to mentally visualize images, can be hard to imagine if you don’t experience it. Larissa MacFarquhar explores the consequences of this phenomenon, including for visual artists, in the New Yorker:

Among the e-mails that Zeman received, there were, to his surprise, several from aphantasic professional artists. One of these was Sheri Paisley (at the time, Sheri Bakes), a painter in her forties who lived in Vancouver. When Sheri was young, she’d had imagery so vivid that she sometimes had difficulty distinguishing it from what was real. She painted intricate likenesses of people and animals; portraiture attracted her because she was interested in psychology. Then, when she was twenty-nine, she had a stroke, and lost her imagery altogether.

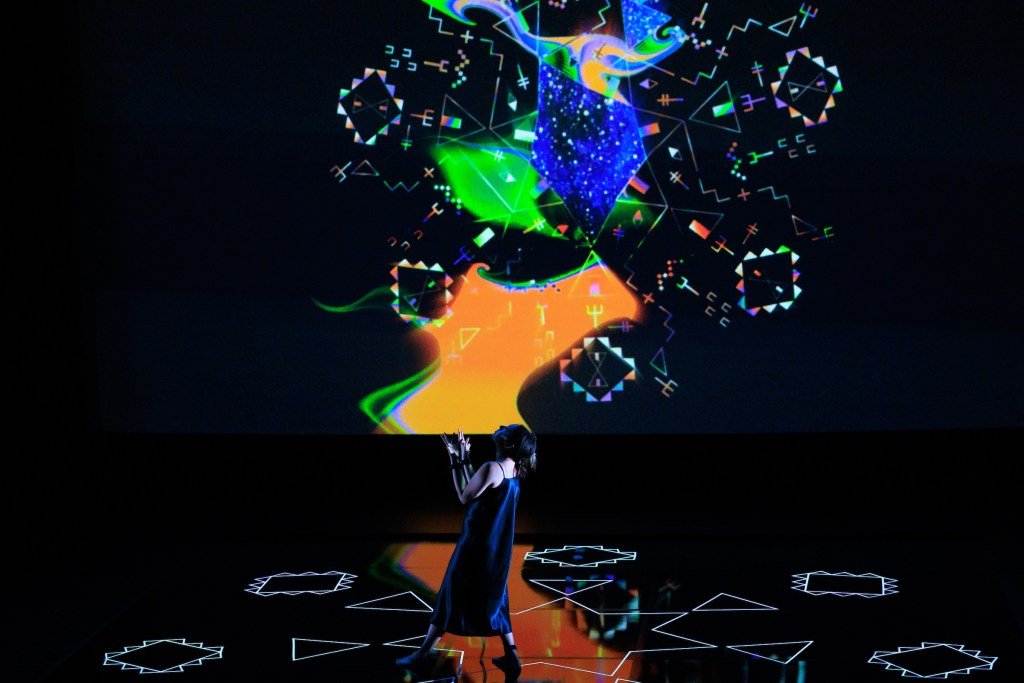

To her, the loss of imagery was a catastrophe. She felt as though her mind were a library that had burned down. She no longer saw herself as a person. Gradually, as she recovered from her stroke, she made her way back to painting, working very slowly. She switched from acrylic paints to oils because acrylics dried too fast. She found that her art had drastically changed. She no longer wanted to paint figuratively; she painted abstractions that looked like galaxies seen through a space telescope. She lost interest in psychology—she wanted to connect to the foundations of the universe.

‣ Novelist Jesmyn Ward writes in Orion about growing up in a sanctuary of Black art and music, specifically hip hop, that continues to shape her definition of home:

I took those rap country tunes with me to college, headphones plugged into my ears. In university, I was so homesick for the South that I hid in my dorm rooms and cried throughout my five years there, wondering how I was going to make it in the world when home had a steel cord affixed to my belly button, constantly pulling me southward and down, back to my siblings, my parents, my friends, the seemingly endless loblolly pine forests and the De-Lisle Bayou spread out like a hand across the horizon. I took poetry workshops to try to express some of these feelings, already returning home in my writing. I hiked the Pacific Northwest and listened to Outkast, marveling at the wordplay, marveling at the storytelling: how they moved the listener through time and space in so few lines. How the empathy they evinced when talking about women felt authentic, real. How Sasha Thumper was worthy of mention, worthy of wistful recounting on André 3000’s part. How that art, and the safety and vision it engendered, was part of my South too.

‣ Dazed‘s James Greig interviewed the service worker who disrupted the British Museum’s “Pink Ball” to protest against the institution’s longstanding sponsorship with BP:

Why did you decide to disrupt the ball?

Alma*: If our institutions, systems and governments are making us complicit in an incredible level of violence then we have to resist at any junction we can, and the British Museum is a very clear nexus of lots of different forms of oppression. It recently hosted an Israeli Independence Day event, for example, and continues to receive sponsorship from BP. BP transports oil from from Azerbaijan to Israel, which is then converted into jet fuel to be used in the genocide. It has also been granted bidding for gas exploration licenses in occupied Palestinian waters.

‣ Joel Berg, director of NYC’s Coalition Against Hunger, traces the Trump administration’s gutting of SNAP and how we can fight back for the Nation:

In their big ugly bill, Trump and his congressional GOP puppets slashed $186 billion out of SNAP, the deepest cut in history, citing the outrageously false charge that most SNAP spending is on “illegal aliens” and “waste, fraud, and abuse.” Not a single House or Senate Democrat voted for the bill, and of the tiny handful of GOP Members of Congress who voted against the bill, most did so because the SNAP cuts weren’t large enough. Contrary to their assertions, the vast majority of SNAP recipients harmed by the cuts are low-paid workers, children, people with disabilities, older Americans, and/or veterans. On top of all that, the Trump administration canceled more than 84 million pounds of food aid scheduled to be distributed by charities, many of which are faith-based.

Then, in an act of reality-denial fit for Noth Korea, the Trump administration ended USDA’s 27-year practice of collecting and publishing food insecurity data, citing variety of preposterous justifications for doing so. Its obvious that their real reason for eliminating this data is their desire to keep the public in the dark about how Trump’s failing tariff and other economic policies— combined with the massive food aid cuts—are causing US hunger to skyrocket even more exponentially. Obviously, the ostrich approach won’t end hunger.

‣ Amitav Ghosh has a piece out in the new publication Equator about the apocalyptic narratives that influence aid agencies’ proposed solutions for climate change, which often do more harm than good:

In short, the grassroots view of the future is completely at odds with that of the credentialled experts. While the latter largely believe that rice farming on coastal land should be abandoned because it will soon become impossible anyway, farmers and local activists are insistent on trying to put a stop to shrimp aquaculture so that the land can be returned to rice farming. In effect, these rural communities are contesting the teleology of anticipatory ruination on which some climate solutions are founded. As Jason Cons notes in his study of how locals and professionals envision the future of coastal Bangladesh, the ideas of the inhabitants of the region are gritty, quotidian and unspectacular, because they “frame the delta not as an immanent site of abstract disaster, but as a lived space of shifting challenges and possibilities”.

‣ Apparently, horror movies can have a surprisingly soothing effect, explains Delaney Rebernik in Time:

Regardless of the motivation, “at the very core of recreational fear lies learning,” says Marc Malmdorf Andersen, the other co-founder of the Recreational Fear Lab. It’s an opportunity for people to engage with the fear part of our human “emotional palette” that many of us don’t experience in daily modern life. “By familiarizing yourself with those states, we believe that they essentially become more predictable” and less overwhelming, Andersen explains.

For people like me, turning to horror to quell anxiety may train our brains to better predict fear signals and suppress overwhelming physiological ones, says Andersen. Because anxiety can cause someone to overestimate a threat, or underestimate their ability to cope, watching horror films might help reset “the comparison that would say, ‘this is the worst,’” says Greg Siegle, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Pittsburgh.

‣ An Urdu anthem for Zohran, courtesy ghazal singer Saima Jahan:

‣ Speaking of which … let’s please take a moment to appreciate these incredible jack-o-lanterns carved by photographer Sam Ahmad:

‣ Diva down:

‣ My girl Mona deserves better:

Required Reading is published every Thursday afternoon and comprises a short list of art-related links to long-form articles, videos, blog posts, or photo essays worth a second look.