Refik Anadol set himself up for failure.

For his latest work, the artist best known for his shapeshifting AI installation at the Museum of Modern Art set out to immortalize a moment of sports legend: Lionel Messi’s 2009 towering header goal for FC Barcelona, which helped clinch its victory against Manchester United in the UEFA Champions League final and secure a historic treble for the Spanish club. In collaboration with Messi himself, who selected the goal as his favorite from over 800 scored throughout his career, Anadol used motion-tracking technology to analyze the athlete’s trajectory, mapping 17 points of Messi’s body in movement and weaving in biometric data like the athlete’s heart rate, breathing, and emotional fluctuations derived from his speech patterns in an interview. Anadol, who utilizes machine learning to produce his immersive abstractions, translated these units of information into an eight-minute installation in which actual footage of the goal and Messi’s recollections collapse onto each other and recede into infinity — a “memory temple,” in the artist’s own words.

It was ambitious. It was unprecedented. It was … underwhelming.

For two weeks in July, “Living Memory: Messi – A Goal in Life” was on public view at Christie’s in New York before selling for $1.8 million in an online auction benefitting the Inter Miami CF Foundation’s philanthropic initiatives. During this period, anyone could see the artwork for free, and as news of its debut gained traction on TikTok and elsewhere, hundreds flocked to Rockefeller Center. When I visited on the morning of Monday, July 21, a Christie’s staffer manning the entrance to the plush second-floor gallery told me they were expecting around 450 people to line up that day.

The piece, housed in a small mirrored room, begins by thrusting us into a dizzying digital landscape resembling what I imagine Anadol thinks the inside of a supercomputer looks like. The audio is staticky, futuristic, and suspenseful, like the soundtrack of an action movie in the scene where the protagonist realizes they are part of something bigger, much bigger. We free-fall into the stadium, whizzing past three-dimensional renderings of Messi’s body in motion and goal sequences in a Bladerunnerey virtual reverie that evokes all the vertigo and adrenaline of a screensaver. The audio is layered with the cheering of crowds and Messi’s own voice describing the moment, the latter largely unintelligible, likely due in part to Messi’s notorious reticence. Words like importante and alegría (“joy”) flicker around us in stereotypical programming typeface. This all turns out to be just an introduction to the actual artwork, which materializes minutes later when a pause of darkness gives way to the recognizable aesthetic of Anadol’s “data sculptures.” Blobs and bubbles with the apparent texture of squishy floam slime bend and stretch like Rorschach pictures seen through a kaleidoscope. Messi’s head melts in slow motion.

“Living Memory” is optically immaculate, and just as soulless. But that might say less about the work itself than about the impossible triangulation of art, sport, and entertainment. By channeling a language as viscerally human as football, Anadol serves up a perfect foil, exposing both the calculated hostility of artificial intelligence and the frigidity of the fine art world.

At Christie’s, I met other football fans who bore blank expressions as they exited the mirrored room. Susan Fisher, a Manhattan resident, learned about the installation on a local news station and had expected to be transported into the match, perhaps with the aid of virtual reality — or at the very least, “to see through Messi’s eyes what it was like,” she said. “And instead, it’s just a lot of … I don’t know, Skittles, moving around.” Her friend Carolina Strauss, a textile artist who was visiting from Argentina, said she had known what to expect, but ultimately found the artwork to be “too much Refik Anadol, too little Messi.”

“One doesn’t see here the way he builds up the goal, the passes. Because that’s what I think Messi is — he’s a group player, he doesn’t play alone,” Strauss added. Indeed, much has been written about the then-Barça midfielder Xavi Hernández’s tremendous pinpoint pass in the 70th minute of the match, expertly finding Messi, who soars so high into the air he loses a boot.

If you’ve been to a football game (or soccer, or better yet, fútbol), you can sympathize with the enormity of what Anadol was tasked with capturing. You’ve tasted the dense air of the stadium, taking in salty gulps of sweat. You’ve let yourself be carried by the waves of chants that roar in and out of earshot, as unified and perpetual as a Greek chorus. You’ve scanned a tiny ball, your gaze unblinking, as players blur across the field, and you’ve felt your pulse race or freeze entirely when anyone inches toward the goal. (There’s a reason a whole bunch of fútbol memes reference defibrillators.) And when your team scores and they collapse to the ground in the purest expression of catharsis, you’ve almost felt the turf scratching under your bare knees, too. You’ve experienced real passion, but also real rage, because the sport brings out our most base, nationalistic instincts.

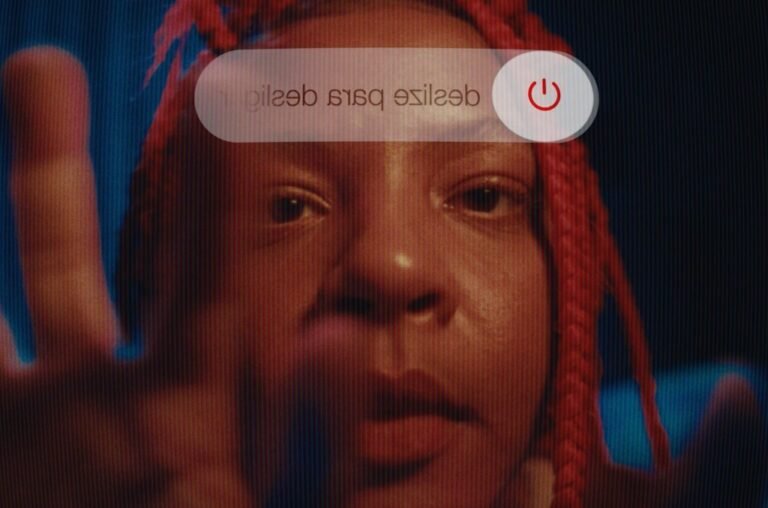

Surely, Anadol could not have been expected to bottle the essence of live football into a work of art like a fragrance. But that’s actually not how most people experience the sport, which is often and sometimes even best watched on television, in a no-frills local bar, surrounded by the warm, electric bodies of one’s friends and enemies. There are numerous examples of poignant screen-based art inspired by football, from Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parenno’s moving portrait of Zinédine Zidane to the music video for Gotan Project’s La Gloria, featuring dancing by Les Twins.

When Argentina won the World Cup in 2022, I watched Gonzalo Montiel score the winning penalty kick achingly far from my native home, sitting on the sidelines of the mythic Brooklyn watering hole known as Turkey’s Nest. Later, I scrolled enviously through photos and footage of the Buenos Aires streets filled to the brim as millions honked and hollered in blissful revelry. I knew that what they were celebrating was not simply a sports triumph, but a much greater glory. There was one clip I watched over and over: a viral video of Telemundo sportscaster Andrés Cantor, who has covered every World Cup since 1990, finally calling the goal for the country where he was born. His iconic GOOOOOOOOOL echoed and trembled just slightly as his eyes welled, and he couldn’t stop saying it: Champions, we’re world champions! Perhaps Anadol’s gravest error was attempting to harness something too real to code, and unlike Messi, he missed the shot. Or, as Strauss brilliantly put it: “Some goals are better shouted.”