Across the country, states are taking back prisons once run by private companies. Oklahoma just bought the Lawton facility for $312 million, ending its last private prison contract. New Mexico is phasing out its last private prison after 27 years. And Texas is bringing seven privately operated state jails under public control as contracts expire and lawmakers approve funding for direct operation.

That sounds like reform, but it is not — at least, not the kind that matters.

The problem has never been the logo on the gate. It is what government pays for and what it requires. Private operators must still follow state policies and inspections while accepting payment terms that reward occupancy. They deliver the results those incentives produce. If the culture stays the same and the payments stay the same, why would the outcomes change?

For decades, prison contracts have paid for heads in beds. Some even guaranteed minimum occupancy. That model fills housing units, not résumés. The Cicero Institute has shown how per-diem and guaranteed-minimum clauses reward full cells rather than rehabilitative results. The point is simple: the contract and the culture, not the organization running the facility, drive behavior.

Private use is smaller than many assume. In 2022, about 90,000 people, roughly 8 percent of all state and federal prisoners, were held in private facilities. Immigration detention is another story. By late 2023, about nine in 10 people held by ICE were in privately operated centers. States may be stepping back, but the industry is not leaving; it is shifting markets.

Public systems face the same problems. National surveys show alarming vacancy rates and turnover that sheriffs feel every day in county jails. The Federal Bureau of Prisons is on the Government Accountability Office’s high-risk list for ongoing management and staffing failures. Congress passed the Federal Prison Oversight Act to strengthen inspections and create an ombuds office, but culture does not change through oversight alone.

In most public-service sectors, private participation is supposed to bring efficiency and innovation. In corrections, contract design prevents both. Bidders compete on cost per bed, not on measurable outcomes. When payment rewards full units, you get more full units, not safer or more effective ones. Public or private, paying for occupancy guarantees the wrong work gets done.

If outcomes are the goal, we should measure them, fund them and make them public.

We already have an example. In 2013, Pennsylvania rewrote its community-corrections contracts so that operators could earn bonuses for lowering recidivism. They also faced penalties if reoffending increased. Early results showed about an 11 percent decline in recidivism in those contracted settings. The approach has since became part of the state’s Justice Reinvestment strategy.

The contract changed behavior. Sentencing laws did not.

The stakes are national. About 95 percent of people in prison today will return home at some point. A federal study of those released in 2012 found that 71 percent were rearrested within five years. Paying for headcounts and compliance checklists will not move those numbers. Paying for outcomes might.

There is a third option. It is not public versus private, but a nonprofit, outcomes-based charter for a single medium-security facility, independently evaluated against a comparable state unit.

Here is what that looks like: Set a flat daily rate that covers safe operations and essential programs. Add capped bonuses and clawbacks for what the public actually values. Use the same budget we already spend. Convert per diems into outcome payments. Fund incentives from verified public savings when people succeed in the community and avoid returning to prison. If savings do not appear, bonuses do not either. Track staff retention, safety incidents, education and treatment completion, verified housing and employment at release, and total cost per resident with equal or better safety. Publish a dashboard every 90 days. If results stall, end the charter. If it works, replicate it.

This idea belongs in jails as well. Sheriffs should be able to contract for results, like fewer assaults, safer housing, completed programs and verified transitions to treatment, with county boards reviewing the same public dashboards.

Real reform will not come from swapping who runs a facility. It will come from rewriting the incentive itself. When contracts pay for safety, stability and reentry success, culture will follow. Change the pay and you change the prison.

Close a private facility if you must. But if you keep the same incentives, you will just keep getting the same results in a different uniform. One answer is to stop paying for occupancy and start paying for outcomes instead.

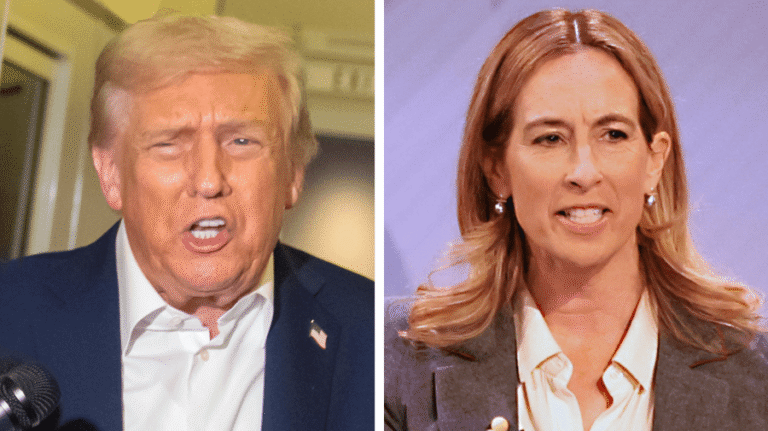

Brian Koehn is CEO of Social Purpose Corrections and a former warden and security expert.