Our built environment contributes to a mental health crisis.

We’re not living in a natural outcome of human needs and behavior. The built environment as we know it—buildings and the spaces between—does direct damage to our minds. Land use planning has had devastating impacts on Americans: economically, socially, and culturally. But I’m not a doomer and I know these things are fixable. Not overnight reversible, but certainly fixable.

Copycat plans

Typical land use rules are written, updated, and enforced at the local government level. But as you might expect, agencies copied each other over the years because why wouldn’t they. Years ago, when I learned some photography techniques that were new to me, I made cheat sheets for other photographers. Much of what I’ve learned as an adult (podcasting, publishing, public speaking, etc.) has been taught by generous people who themselves had learned tips and tricks. So of course public agencies copied each other with their rule-making. “That worked for a similar river city? Let’s try it here.”

Planning departments at city and county levels weren’t setting out to guide development in a way that would purposefully harm people. Quite the opposite.

If a new Sears distribution center was coming to town, they’d want to map out a plan to accommodate all the new employees and subsequent traffic. In the middle of the 20th century, planners were still very much concerned about separating dirty and/or dangerous land uses from residential areas. The result was that all across the country, local development rules required or incentivized development patterns that spread everyone and everything across the landscape.

A work zone, school zone, shopping zone, entertainment zone, and a sleep zone were established. And then each major category started getting more prescriptive subcategories. “Residential” morphed into single-family, multi-family (apartments), and condos. But wait, there’s more! Residential land uses started to be regulated by local governments according to lot size: garden apartments, planned unit developments, and subdivisions were each given rules. Residential was also regulated by the type of people living in a place: public housing, group dwellings, age-restricted dwelling, renters, and owners.

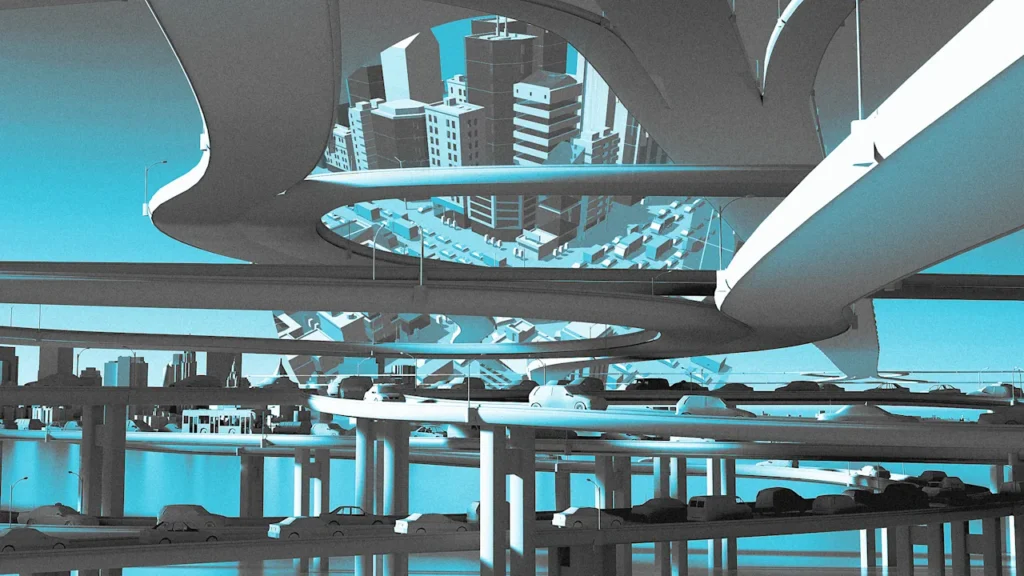

Local regulations created (and continue to create) sprawl in cities, not just the suburbs.

The traffic factor

Land use planning requires traffic engineering analysis, a process prioritizing speedy car movement above all else. Wider roads and intersections are not just suggested but required with the express goal to move vehicular traffic from zone to zone as quickly as possible. This has been going on for nearly 100 years without taking a foot off the brake.

The obvious outcome of modern land use planning is that Americans drive everywhere all the time. Not just work commutes, but all the errands before, during, and after work. Half of our car trips are less than a few miles long. A quarter are less than one mile. Less than a mile in a car by ourselves.

The mental health connection

Life in a single-occupant vehicle has its perks, like singing along to music or listening to podcasts uninterrupted. It also has its pains, like separation from other humans and mental deterioration.

Loneliness is a significant variable affecting depression. It’s a predisposing factor. Cigna conducted a study of 20,000 Americans, and reported a jaw-dropping finding: nearly half of adults sometimes or always feel alone. 40% said their relationships aren’t meaningful and they feel isolated.

Dr. Julianne Holt-Lunstad is a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University. She says the health risks of missing out on social connection is like smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

Worse yet, there’s a causal relationship between social isolation and suicide. Conversely, having a crew (“social support” in doctor jargon) has a protective effect against suicide. For every suicidal death, another 20 people attempted suicide.

The takeaway

So what do you do with all this heavy information?

First, remember that the built environment is deliberately planned for us to drive in cars from zone to zone. Planners aren’t trying to destroy our minds, but the built environment increases anxiety, depression, isolation, loneliness, and suicide.

Second, understand the land use catastrophes are reversible. Compact development won’t be legalized overnight, but reform can come as quickly as local leaders are willing. Walk-friendly, bike-friendly, transit-friendly places are good medicine, and they’re made possible at the local level.

Third, and most important of all, know that things can get better in the end. America’s built environment does not fit who we are as humans, but we can turn this around with something as boring as reforming land use planning. Start by legalizing healthy infrastructure—a variety of land uses within walking distance of homes and streets designed for safe walking and cycling.