Are branding agencies talking about AI so much because it’s actually useful… or just to keep investors happy?

Recently I attended Upscale

in Málaga, Spain. It’s a conference organised by Freepik, which offers a suite of AI tools for creating and editing content. So naturally, I was expecting a lot of blind cheerleading for AI. But the tone of some of the talks was surprisingly nuanced. And the most eye-opening session came from Max Ottignon, co-founder of Ragged Edge.

Max covered a lot of ground about the pros and cons of using AI in branding. But one revelation really stood out. “I spoke to a design leader the other day,” he said. “Apparently, their designers tell their bosses they’re using AI. But the reality is they’re trying to avoid it. It slows them down. It’s an inhibitor to their creativity.”

Wait, what? Designers are pretending to use AI when they’re not? Apparently, this is not one isolated case. “I spoke to a CEO of a client—I won’t name them—who told me: ‘We have to exaggerate the impact of AI that we’re having to our investors. The investors expect it.'”

So what’s going on here? Well, Max thinks the problem is simple: some people have got the wrong idea about what AI is actually for. They think it’s about making branding faster and cheaper. But that’s completely missing the point of what branding is supposed to do.

The bigger problem

Before we even got to AI, Max pointed out something uncomfortable: branding has been pretty generic for years now. This isn’t a new problem; AI has just made it worse.

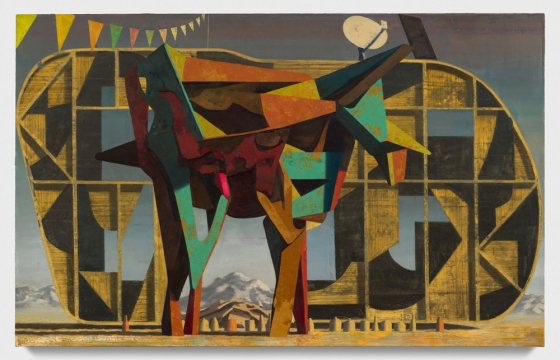

To demonstrate, his team spent half a day creating a fake brand called Levo. They gave it all the usual stuff: a friendly name, a warm, crafted logotype, a modern colour palette, some expressive illustrations, and a snappy slogan. “Live, laugh, leave. I actually think that’s pretty good,” Max joked.

And there you go: instant brand. Except here’s the problem: it’s so generic it could be literally anything. “You’ve got this amazing brand of effortless tomato sauce. Or have you got a payments brand?” The brand is so commoditised, Max argued, that it’s essentially meaningless.

This is the trap agencies have fallen into. They’re treating branding like it’s performance marketing, and it really isn’t.

Why efficiency is the wrong goal

“Don’t get me wrong,” he adds. “AI is fantastic at certain things. It’s so good at performance marketing, about creating short-term conversion-focused, contextual, personalised, low-cost, measured-in-seconds assets. It’s amazing for that.”

But branding works completely differently. It’s not about quick conversions or personalised messaging. “Branding is about the long-term. It’s about driving awareness. You have to be really consistent over time. You have to create a shared meaning around millions of people.”

And the stakes are much higher. A single brand asset might cost millions to produce and distribute. You might not know if it worked for years, possibly decades.

So when everyone’s obsessing over making branding more efficient with AI, they’re kind of missing the point. Fast and cheap isn’t what branding needs to be. It needs to be memorable and distinctive. And that takes time, thought, and craft.

Even the AI companies get it

Here’s the clincher to his argument: the AI companies themselves aren’t using AI to create efficient, cheap branding. OpenAI works with top-tier agencies like Drive Mother and Studio Dunbar, commissioning custom typefaces from foundries like Dynamo. Anthropic is running “this big, big brand campaign that feels so human, that’s got an idea at the heart of it. It’s nothing like the sort of slop some people are producing.”

Why? Because the fundamental job of branding hasn’t changed since people started branding cows in 2000 BC. “The whole point of a brand, the sole point of a brand has been to make your product, your organisation, your service uniquely recognisable. That is the point of branding.”

And to be recognisable, you have to be different. Max cited the Von Restorff effect, a 1933 study showing that in a series of similar things, the most different one gets remembered. His example: the Paris 2024 Olympics.

“Incredible achievement, sporting greatness. There was an incredible 100-metre final. Yet I can’t really remember what happened, if I’m honest. But what I do remember is this. I do remember Raygun,” he said, referring to the Australian breakdancer (real name Rachel Gunn) whose unconventional performance went massively viral during the Games, despite not even making it past the round-robin stage.

“That’s what the internet got excited about. This is what gets people excited: what’s different. And different is really, really hard.”

So how should agencies actually use AI?

Max outlined three principles that Ragged Edge follows when working with AI. They’re all about prioritising difference over efficiency.

1. Fight for quality, not quantity. The rule is simple: “Don’t ship anything unless it’s the same quality or better than anything we’d make without AI.”

2. Start with ideas, not aesthetics. This might be the most important principle. “If you start with an aesthetic, if you start with the same place everybody else has been, you’ll end up in the same place everybody else has been.” At Ragged Edge, they have a rule for the beginning of projects: “Bring anything you like to the table. It could be a meme, it could be a song, it could be a poem, anything but an aesthetic.”

For Zar, a currency conversion service helping people in countries with unstable currencies, the team started with a concept: a rock. “You can take all these unstable currencies and you can turn them into a rock, the rock-solid dollar.”

AI enabled them to rapidly explore many visual directions during the concept phase, testing different models and typography. Then came “the craft and the graft, literally carving out the letters, developing the logo.” The whole process took a year. “The idea made it different. The AI made it possible. And the craft and the commitment made it real.”

3. Embrace a growth mindset. Max was honest about the frustrations of working with AI. Early experiments with AI video for a bottle rotation were a disaster. “And then we got to this final one. And we were like, you know what? Fuck this. What even is that?”

Many in the creative community have had similar experiences and given up. But that’s a mistake, he argues. “Being wary of AI is incredibly rational,” he acknowledged. But the industry has been here before.

Ragged Edge was founded in 2007 because Max and his co-founder “could think digitally, when everybody else was only thinking in print design. That’s how old I am.” Later, early adoption of Figma put them ahead in digital product design. “This shift is the same shift we all have to make here.”

What it looks like in practice

Today, everyone at Ragged Edge uses AI daily. But here’s the thing: “They’re all using it in different ways. Everybody is using it in a fundamentally different way to solve a very specific problem, a big problem, a small problem.” And crucially: “It doesn’t make our projects faster, it doesn’t make them cheaper, doesn’t make them more efficient, but it makes them better.”

Recent projects show how this plays out. For SolFlare, a crypto wallet, they tried using AI for the illustration system, but couldn’t get it quite perfect, so it was primarily used in the concept phase. For Tilt, a US credit brand, AI helped explore broader ideas and animate elements. For Palmetto, a climate tech business, they used it more integratively, seamlessly blending AI-generated content with real photography and film. “It’s seamless, but it has enabled us to do stuff that we wouldn’t have been able to do otherwise.”

Max quoted a client at Wise: “AI will make good designers better, and it will make bad designers faster. I think that is very, very true.”

The real enemy

Max concluded that the creative industry is indeed in a fight right now. But it’s not against AI. “As a creative industry right now, I believe this: we are in a fight, but it isn’t against AI, it’s against apathy. We are in a fight against apathy, against people who want things faster and quicker, who want things more efficiently, who want things to cost less; they don’t care about the quality.”

And so here was his call to arms: “We need to come together as an industry, we need to fight for time, we need to fight for thinking, we need to fight for quality, we need to fight for experimentation, we need to fight for craft, and fundamentally, we have to fight for difference. We have to fight for difference, and I think if difference wins, we as a group, as a creative industry, we all win.”