The ‘Make in India’ scheme, launched in September 2014 and was marketed as a revolutionary economic strategy to make India a world manufacturing centre. With its ambitious goals of increasing manufacturing to 25% of GDP, generating 100 million jobs, and drawing foreign direct investment (FDI), the plan is guaranteed to transform India’s manufacturing sector.

A decade on, the imprint of ‘Make in India’ is felt in every sector. But the question is: has the scheme lived up to its potential?

The Vision vs. the Reality

At the centre of it all, ‘Make in India’ was supposed to:

- Increase the manufacturing contribution to GDP to 25% by 2022.

- Generate 100 million jobs by 2022.

- Considerably increase FDI and exports.

- Decrease import dependence in major sectors.

Manufacturing GDP share? At 15% in FY14, it remains mostly stuck at about 17.7% a decade later, which is still way short of 25% (New Indian Express, 2024).

Job creation? Only 18.5 million jobs have been added in manufacturing as of 2024, as per the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), short of even 20% of the initial target (Hindu, 2024).

Successes Worth Mentioning

Despite the gaps, some achievements are noteworthy:

- Electronics and mobile production have increased, partly owing to the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) programs. India is currently the second-largest producer of mobile phones in the world (PIB, 2023).

- Automotive and electric vehicles (EVs) have received robust policy intervention and investment. Ola Electric, Tata, and TVS have invested in increasing manufacturing and R&D facilities.

- Pharmaceuticals and defence production have increased domestically, partly due to strategic policy reforms and purchases from Indian suppliers.

Yet, these gains are still sector-driven and not yet a pan-industrial turnaround.

FDI: Increasing Inflows, But with Exceptions

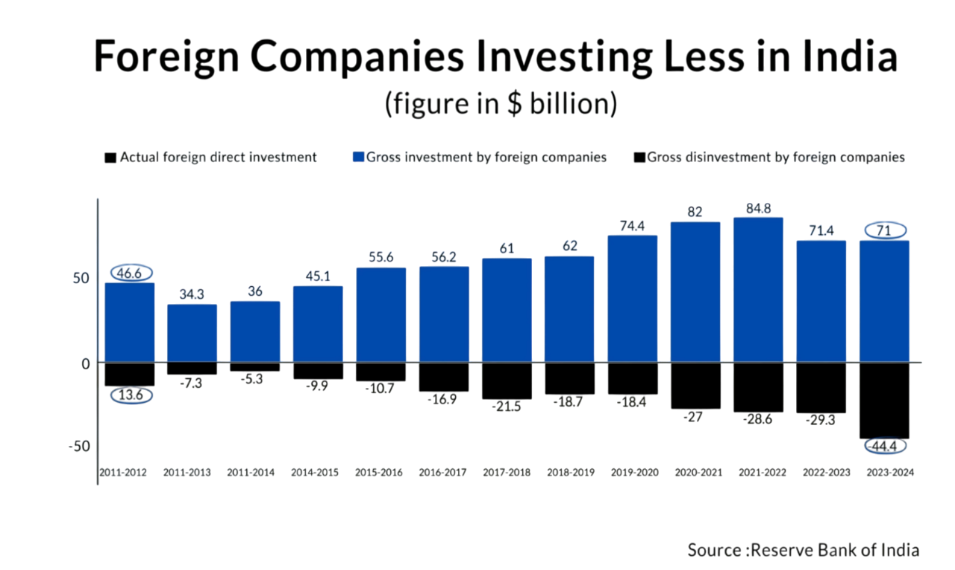

FDI inflows have, in fact, increased from $46 billion in 2014 to $71 billion in 2023. Yet, disinvestments also jumped from $13.6 billion to $44.4 billion, reducing net gains (180DC SRCC, 2024).

Furthermore, most of the FDI has gone into services and technology sectors, rather than the core manufacturing. The government’s intransigent attitude, as evidenced in the Tesla case, has at times killed flexibility that overseas investors anticipate (Scroll, 2024).

Trade Balance: Exports Up, But Imports Too

Exports have more than doubled from $375 billion in 2014 to $776 billion in 2023 (India Today, 2025). However, import growth has surpassed export growth, leading to a wider trade deficit of $54.5 billion in 2024, up from $32.4 billion in 2014.

Structural and Policy Bottlenecks

1. Red Tape & Ease of Doing Business

Despite communications on single-window clearances and ease of doing business, the ground reality is different. Establishing operations (ranging from company registration to land acquisition) involves interministerial approvals and bureaucratic layers. File movement delays, topped by absenteeism or procedural stickiness, can keep industrial projects stuck for years (The Hindu Op-Ed, 2020).

For example, even company registration could be done in 15–30 days, but obtaining land, environmental clearances, and commencing construction would take 1.5 to 5 years, while in Vietnam, it would be only 6 months.

2. Import Tariffs That Dissuade Entry

India’s steep import tariffs have been a strong disincentive for international players, particularly in high-tech areas. India imposed 100% import duties on electric vehicles (EVs) in 2021, making foreign brands like Tesla uncompetitive in entering the Indian market before establishing manufacturing operations.

3. Environmental Clearances: A Systemic Roadblock

Environmental clearances have been another bottleneck. More than 1,000 projects in Gujarat alone were held up as of mid-2024 due to the delay in green clearance. What ought to be a speedy process for essential infrastructure takes years, undermining investor sentiment and increasing the costs of the project.

4. Land Acquisition: The Achilles’ Heel

Land acquisition continues to be one of India’s most long-standing policy failures.

Consider South Korea’s POSCO, which had planned to invest $12 billion in a steel plant in Odisha, the single largest FDI proposal at the time. Despite memorandums being signed in 2005, the project got entangled in protests, bureaucratic delays, and clearance roadblocks. After a 10-year stalemate, POSCO officially withdrew in 2017 (Think School, 2024).

And it is not only foreign players. Domestic infrastructure projects are stuck in land-related limbo, too.

- Bharat Mala Project: Initiated in 2017 to construct 34,800 km of national highways, it was to be finished by 2022. By 2024, just 23% of the work is done, and the Ministry has now extended the deadline to 2027. Cost per km has risen to ₹32 crore, more than doubling the total spending from ₹5.35 lakh crore to ₹10.63 lakh crore.

- Mumbai–Ahmedabad Bullet Train: Earlier touted as India’s new infrastructure crown jewel, it was to be finished in 2023. Land acquisition delays, particularly in Maharashtra, have now pushed the deadline to 2028, and the cost has escalated to ₹2 lakh crore.

Such delays not only cause cost escalations but also cascade through the generation of jobs, inflows of investment, and public opinion.

4. Skills Deficit

Just 2% of India’s workforce possess certified technical skills, as opposed to 96% in South Korea and 40% in China (Skill India Report, 2024).

The Skill India mission has tried, yet just 5% of India’s workforce has been formally trained so far. Most B.Tech, ITI, and polytechnic graduates are jobless.

What Needs Fixing: Urgent Reforms

- Ease of Doing Business: Change the processes, not the laws. Empower local government, simplify digital clearances, and cut unnecessary paperwork.

- Land Banks & Acquisition Reform: Scale Gujarat’s land bank model. Ensure community participation and transparent compensation schemes.

- Infrastructure Upgrade: Expand freight corridor development, port updates, and last-mile logistics. Shorten turnaround times with investments in smarter technology and process automation.

- Skilling at Scale: Connect skilling initiatives to industry needs. Scale up apprenticeship models, vocational training, and public-private partnerships in technical education.

Future Outlook

Make in India was not an all-out failure. It did spur discussions and policy focus towards manufacturing. But the program has mostly underachieved due to structural rigidities, bureaucratic resistance, and sluggish infrastructure expansion.

With India’s goal of becoming a $5 trillion economy, manufacturing should take centre stage, not merely in GDP contribution but also in job creation and import substitution. The subsequent phase needs to be bold, multi-stakeholder, and reform-oriented.

The vision is still deserving. But the implementation now must catch up.

Written by – Krishna Murugappan Edited by – Neelambika Kumari Devi

The post Make in India: The Reality of Where We Stand appeared first on The Economic Transcript.