I’m a staunch believer that Lorna Simpson is one of the most important photographers of her generation, so I’m pained to report that Source Notes — a monographic exhibition of the artist’s paintings at The Met — is a mixed bag. Conceptually, the work is just as strong as ever: The painted screenprints collage together archival images from Ebony and Jet magazines, fusing these touchstones of Black culture with images of Arctic glaciers and, more recently, the rocky forms of meteorites. Simpson grounds this combination in riveting historical fact, including the story of the African-American Arctic explorer Matthew Henson, who was potentially the first person to reach the North Pole in 1909. She thus positions Black history squarely in the Romantic painterly tradition of the Burkean sublime, which sought to capture the combined sense of fear and awe that one feels in the face of an immense, unvanquishable landscape — think Caspar David Friedrich’s “The Sea of Ice” (1823–24) or Peder Balke’s “From Nordland” (c. 1860–69), to name just two other artists with recent Met exhibitions. Art history nerds, in other words, will love this.

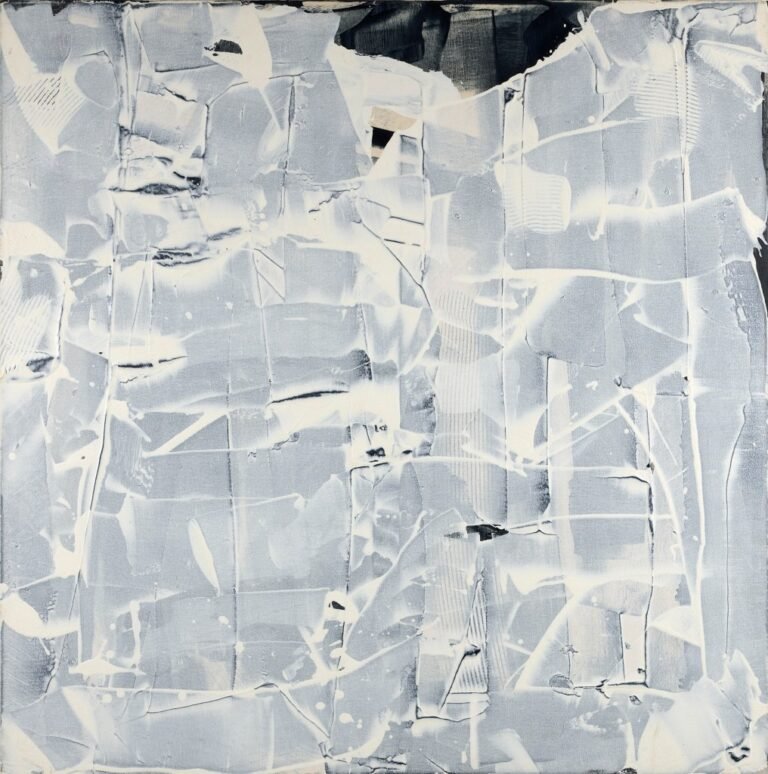

The problem is that this monumental move does not always hold up at the paintings’ monumental scale. Seriously, these works are enormous: 12 by 8 1/2 feet (~3.7 by 2.6 meters) in some cases. But while every square inch of Simpson’s photographic work packs a compositional punch, these paintings sometimes feel like JPEGs that have been blown up beyond their optimal resolution. (In keeping with this, the work photographs better than it looks in real life, as the composition comes into focus at smartphone size.) Owing in part to the flatness of the canvas’s surface, certain works can feel deflated by large stretches of space that just aren’t doing that much when you get up close to them. Paintings like “Ice 8” (2018) or “Vanish” (2019) lack visual density in person and, I’m sorry to say, don’t reward deep looking the way Simpson’s other work does. Though the scale reflects the immensity of the subject matter, I wonder whether it was partly determined by the incessant market pressure for artists to go bigger and bigger. Either way, the smaller photo collage pieces — relegated to sitting flat under a glass case — are some of the best-articulated works in the show.

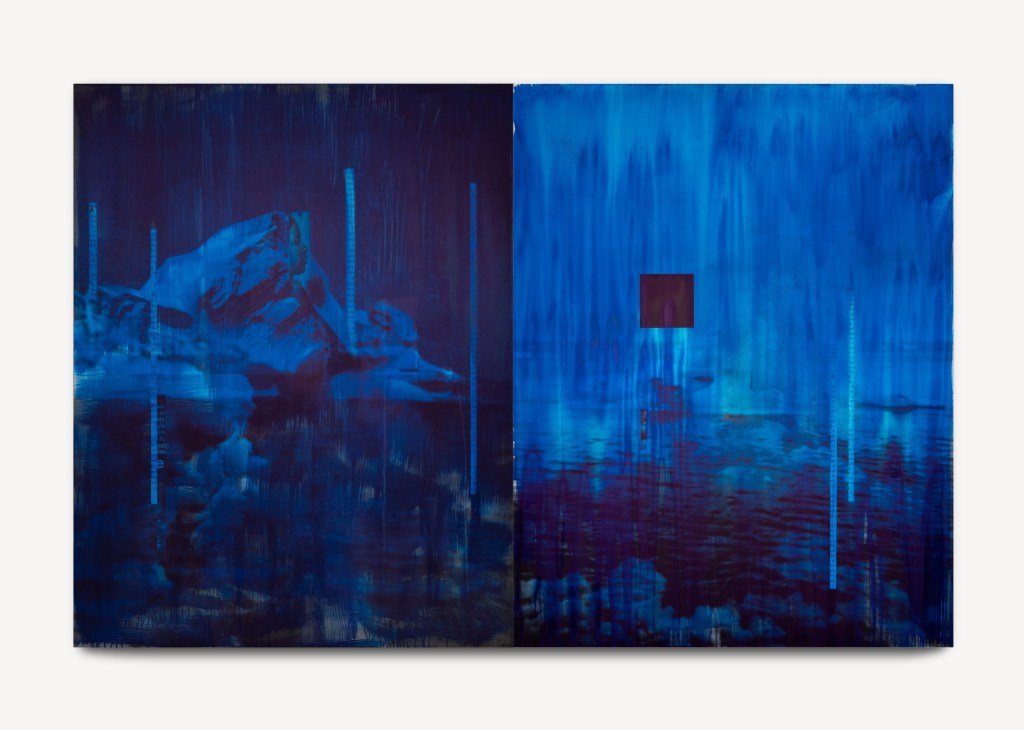

But don’t take this as an invective for photographers to “stay in their lane” or other such nonsense. Two paintings in particular speak to Simpson’s potential within the medium: “Night Fall” (2023) is the icy portrait of a woman superimposed over an upside-down waterfall, the paint tumbling and twisting from her chest like blue dye through a glass of water. The craggy lines of the rocks that frame her face unfold like the wings of a blue morpho butterfly. Just stepping into the room feels like a cold plunge. It’s a tremendous work, and kudos to whichever “private collection” managed to snag it. (Please, leave it to a museum!) “Detroit (Ode to G.)” (2016) also feels firmer than the other paintings on view, perhaps because its modular components give it more internal compositional pressure, like the literal combustion it depicts.

Perhaps the unevenness of Source Notes is a result of The Met pushing the show out before the work was fully gestated. Whatever the reason, it left me yearning for an alternate version of the exhibition in which a tighter painting selection hung side-by-side with her brilliant photo collages, showcasing the full power of Simpson’s artistic punch.

Lorna Simpson: Source Notes continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through November 30. The exhibition was curated by Lauren Rosati.