HOUSTON — On April 5, 1968, the day after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, Joe Overstreet began a new painting. The piece that would become “Justice, Faith, Hope, and Peace” (1968) takes its title from King’s impassioned words, which Overstreet interprets as colliding angles, target-like rings, and diamond-shaped central panels, diverging from the rectangular picture plane to form a sort of shield. Spanning some 7.5 by 16 feet, the massive, four-paneled work emits an explosive sense of pressure and upheaval that reflects the moment of its creation.

Two years later, the painting’s two central panels were sent from Overstreet’s New York studio to Houston for a group show organized by Dominique and John de Menil, socially conscious art patrons and future founders of the Menil Collection. The couple invited Overstreet to Houston again in 1972 for two solo exhibitions and purchased a number of his works. But the two panels from his 1968 painting were never shown in the city and remained in storage until the artist asked for their return nearly 10 years later. In his exchange with Dominique (John de Menil died in 1973), Overstreet wrote that he’d “like very much to show my work in Houston again someday.” That day has finally come.

Joe Overstreeet: Taking Flight at the Menil Collection shines a long-overdue spotlight on an astonishingly innovative artist who explored the Black experience in the United States through abstraction. All four panels of “Justice, Faith, Hope, and Peace” have been reunited for the exhibition. Thoughtfully curated by Natalie Dupêcher, the show also features pieces from three of the artist’s major series. Visually, the works’ brilliant colors and inventive forms are breathtaking, but a closer look reveals deeper messages about the complicated political world in which the artist lived.

Born in rural Conehatta, Mississippi, in 1933, Overstreet and his family left the South in the early 1940s and eventually settled in Berkeley, California. The artist joined the US Merchant Marine before establishing his first studio in San Francisco, where Beat poetry, jazz music, and the artist Sargent Johnson were formative influences. A move to the Upper West Side of New York City in 1958 introduced him to an older generation of painters like Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, and in 1960, Overstreet joined Ellsworth Ausby, Sun Ra, and other members of the vibrant Black arts and music scene on the city’s Lower East Side.

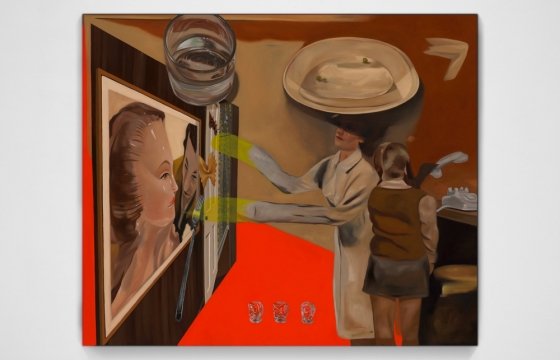

By the mid-1960s, Overstreet was a prominent figure in the Black Arts Movement. He created his paintings “with a message about the time, about Black people and about this country,” he later stated (quoted in the exhibition catalog). A fundamental part of his mission was to break free of the flat, rectangular picture plane that had characterized so much of Western art history; he wanted to forge an alternative to the Eurocentric view of painting that continued to dominate American art. In 1967, he began building elaborate shaped canvases, like those of “Justice, Faith, Hope, and Peace,” and abandoned stretchers entirely just three years later.

Overstreet is perhaps best known for his Flight Patterns works, composed of unstretched painted and stained canvas suspended mid-air by ropes anchored to the gallery walls, floors, and ceiling. The dazzling, seemingly airborne forms resemble kites, sails, flags, or tents that enliven the space with their radiant color. But carefully chosen titles like “We Came from There to Get Here” (1970) and noose-like knots — an intentional reference to the history of race-based lynchings in the United States — allude to more pertinent issues in American society. In each piece, multiple points of tension, caused by binding and pulling, reflect the extreme strain on Overstreet and many other activists and artists as the Civil Rights movement, Vietnam War, and political unrest in the US intersected in the 1960s and ’70s.

“The tension is really key to the comment he’s making about life in the United States in the early 1970s with the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights and Black Power movements,” Dupêcher told Hyperallergic on a recent tour of the exhibition. Overstreet, who died in 2019, indicated that his Flight Patterns could be positioned differently in future installations, so that they change slightly with each exhibition. But he stipulated that they must always be stretched tight, with at least one noose tied to every piece.

The final group of works on view emerged from Overstreet’s pivotal journey to Senegal in 1992. Visiting the country for a group exhibition and biennial, he was inspired by its bright light and glimmering, dusty atmosphere. But the artist was was especially impacted by Gorée Island, a major outpost of the transatlantic slave trade for over 300 years. A trip to a cell block known as the Maison des esclaves, or House of Slaves, prompted him to begin work on a new series of wall-sized paintings shortly after his return to New York.

Overstreet’s Senegal pieces immerse the viewer in lush layers of pastel oil paint and beeswax that give off a quiet, almost impressionistic glow. The works are disarmingly beautiful, and some viewers may only experience them as such — titles reference Gorée subtly, and the Menil does not include didactic wall texts in its galleries. But, like Flight Patterns, these works utilize the pleasures of paint and color to respond to deep pain. Each 10-by-12-foot painting is modeled on the size of the once-crowded cells at Gorée, and feathery, repeated marks suggest footsteps pacing across the canvases. These works have not been displayed publicly for nearly 30 years, so seeing them — along with so much of Overstreet’s complex and stunning art — is a rare and profound privilege.

Joe Overstreeet: Taking Flight continues at the Menil Collection (1533 Sul Ross Street, Houston, Texas) through July 13. The exhibition was curated by Natalie Dupêcher in collaboration with the artist’s estate.

Editor’s Note: Hyperallergic’s standard image policy is to run photographs taken by our reviewers to authentically represent their experience. An exception was made in this review due to the venue’s restrictions on photography.