A year ago, direct air capture—technology that pulls CO2 from the air—seemed ready to quickly scale in the U.S.

Project Cypress, a massive undertaking in Louisiana designed to capture more than a million tons of CO2 each year, won $50 million in funding from the Department of Energy in early 2024. In Texas, another major direct air capture hub also won funding. Together, the projects were eligible for as much as $1.1 billion from the DOE, part of $3.5 billion Congress set aside for DAC hubs in the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

Climeworks, a pioneer in the industry and one of the partners on the Louisiana project, was hiring a U.S. team, scaling up a new plant in Iceland, and signing large deals to sell carbon removal to companies like British Airways and Morgan Stanley. Heirloom, another tech company working on the Louisiana hub, closed a $150 million Series B round of funding. CarbonCapture, another startup in the space, raised $80 million. Multiple other DAC projects also won DOE grants.

The situation is different now. In one round of cuts, according to a leaked list, the DOE might revoke around $50 million in grants to 10 different direct air capture projects. (The cuts are part of more than $7.5 billion in cancellations for what the administration calls “Green New Scam” funding.) A second leaked spreadsheet suggests that the flagship hubs in Louisiana and Texas might also be at risk. Earlier this year, Heirloom laid off some workers and reportedly canceled a planned project. Climeworks also had a round of layoffs.

At the same time, a few projects are moving forward, and one key tax credit is still in place. Government support isn’t the only thing keeping the industry afloat. But the technology is still in the so-called valley of death—the stage when it still hasn’t reached large-scale commercial deployment—and funding cuts would be a major blow. Even as other countries offer incentives, it could slow down the industry globally.

“I think it could slow down substantially,” says Eric O’Rear, associate director at the economic and policy research firm the Rhodium Group. “If you look at it from a policy perspective, the U.S. was really dominating this space.”

From boom to uncertainty

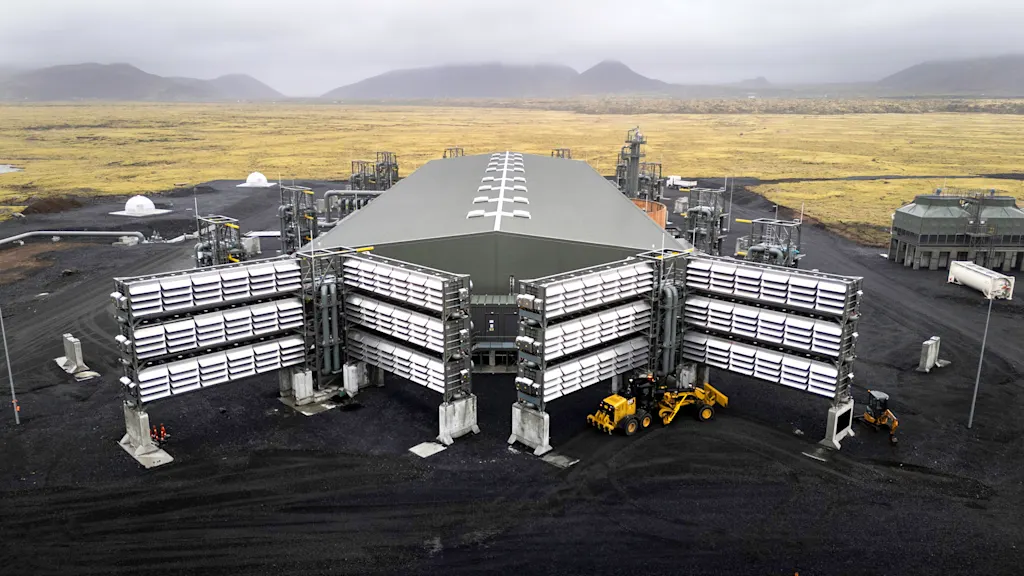

As an industry, direct air capture is still in its infancy. The technology was proven in a lab 26 years ago, but the first commercial plant, run by Climeworks in Iceland, didn’t open until 2021. It was a milestone, but tiny compared to what’s needed: It captures 4,000 tons of CO2 a year, or roughly as much as driving 930 gas cars over the same period. To deal with climate change, the world may need to capture 10 billion tons of CO2 a year by the middle of the century, according to one National Academy of Sciences estimate. (That’s on top of radically cutting emissions, not as a replacement.)

Critics have argued that the technology is too expensive to be a realistic solution. But the companies developing it say that scaling up will bring costs down, both because of economies of scale and because engineers can learn by doing, improving materials and processes as they go.

“Our approach, ‘deployment-led innovation,’ involves running DAC plants in the field for rapid, real-world learning,” Climeworks CEO Christoph Gebald told Fast Company in 2024. Now the company says that one key component of its tech, the sorbent, lasts 10 times longer than before, and it’s working on cutting its energy use in half, which would also cut costs in half.

The company aims for a cost of $250 to $350 per ton captured by 2030. Ultimately, the industry aims to achieve $100 per ton—a tipping point that would make it affordable enough to be deployed at a very large scale. The first corporate buyers are early-stage adopters willing to pay much higher prices to help the technology grow.

The two large planned DAC plants in Louisiana and Texas could help accelerate that process. But the future of those projects is still not clear.

In a statement after a leaked spreadsheet listed the projects, the Department of Energy said that “no additional projects have been terminated,” and that the DOE “continues to conduct an individualized and thorough review of financial awards made by the previous administration.” Both projects have bipartisan support from state leaders, and when they were on a DOE “hit list” earlier in 2025, Republican leaders helped keep Project Cypress alive, at least temporarily. But it’s possible neither project will continue.

Smaller direct air capture hubs that had planned on DOE funding may also struggle to continue—or possibly move. CarbonCapture, a startup that planned to install its tech in Arizona this year, has already relocated that project to Canada, to a site called Deep Sky that’s designed to help multiple companies scale up their technology in one place. Deep Sky announced last week that it plans to build a second large facility in Canada. The Canadian government offers strong incentives for DAC companies to build new plants. Some other countries, from Denmark to Japan, also have incentives for DAC projects.

“Globally, we are seeing carbon removal continuing to scale,” says Ben Rubin, executive director of the Carbon Business Council. “I think the big question is, who will be home to those economic benefits and who will be home to those jobs?” Project Cypress, for example, was expected to create 2,300 jobs and bring billions of dollars to Louisiana’s economy.

For the climate, it doesn’t matter if direct air capture happens in the U.S. or Iceland or Kenya. But the U.S. government, under President Joe Biden, started to take a leadership role in helping the tech grow faster. The political changes could slow global progress.

What’s moving forward

Some DAC projects are still underway, with or without government support. In Texas, 1PointFive, a subsidiary of the oil giant Occidental, is building a sprawling facility that could capture up to 500,000 tons of CO2 a year. 1PointFive told Fast Company that the facility is on track to start running this year—at which point it will be the largest direct air capture operation in the world.

Some of the captured CO2 could be injected underground to help get more oil out of old oil wells, a controversial move from a climate perspective. But some of it will also be permanently stored in deep rock formations or depleted oil or gas wells. Earlier this year, the Environmental Protection Agency granted the company permits to inject millions of tons of CO2 in storage wells over the next 12 years. The captured CO2 could also be used to make everything from plastic to jet fuel.

The project, called Stratos, doesn’t have any DOE funding. Microsoft, one of the project’s customers, agreed in 2024 to buy 500,000 tons of CO2 removal over the next six years, with the caveat that the CO2 won’t be used in oil production. BlackRock invested $550 million; the total cost may be more than $1.3 billion.

Others are moving forward with smaller pilots. Avnos, a California-based startup, is nearing completion on a pilot called Project Brighton that was funded by the U.S. Office of Naval Research, and plans to begin operation before the end of the year.

The company has an unusual hybrid approach that could potentially reach low costs earlier than others like Climeworks. Along with capturing CO2, it also captures water. The tech’s design means that it can cut energy use in half or more, dramatically cutting the overall expense. (At its first large project, it expects to capture CO2 for less than $250 per ton; as it scales up, CEO Will Kain says, it has a “good line of sight” to $100 per ton.)

Because the technology produces water from the air, it also has the opportunity to potentially be used at water-hungry data centers, or at facilities that want to use CO2 to make products like chemicals and need water for those processes as well. Avnos is involved in DAC hub projects with DOE funding, and hasn’t yet heard what the ultimate fate of those projects will be. But it also has deliberately looked for a variety of sources of funding for other projects. “We’re diversifying our sources of funding,” Kain says.

How the industry could keep growing

Kain is still optimistic about the industry. “The global momentum for carbon removal is very strong,” he says. Even in the U.S., when most of the clean energy tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act were axed by Congress this summer, a tax credit for direct air capture stayed in place and was actually expanded. (Now projects that use CO2 to make other products can get the same incentive as projects that permanently store CO2 underground.) If federal support for new projects wanes, as expected, “it certainly makes it harder for us to deploy first-of-a-kind pilots in the U.S.,” Kain says. “So companies like us have to get a little bit creative in how you fund.”

Some companies are also working on new ways to lower the cost of direct air capture and work without government grants, including a Denver-based startup called Heimdal. The company has an unusual approach: Instead of using large fans to pull in air and extract CO2, it uses calcium oxide, a mineral that naturally reacts with the gas to capture it. “It’s very simple,” says Marcus Lima, cofounder and CEO. “It’s literally just spraying rocks on the ground.” The rocks are later heated up in a kiln to release the CO2 for storage or use. The cost is already low, at around $200 per ton.

The startup opened a facility in Oklahoma in August 2024 that can capture up to 5,000 tons of CO2 per year. To help with costs, it makes some compromises that some competitors wouldn’t—selling the CO2 for use in oil production, and using natural gas as an energy source. But Lima argues that those are stepping stones toward an ideal for future operation. He also believes that companies should focus on bringing costs down without relying on grants.

“My view is, at least for capital projects, federal funding should serve as an accelerant, as an enabler,” he says. “What we’re seeing now with the change of administration and the general cooling in the climate-tech capital markets is kind of a return to earth. Reality now starts to matter a lot more, because you don’t have hundreds of millions of dollars in the venture markets that you can just have like that. Projects need to make money.”

Even companies with lower costs may face more challenges in getting investment now. “With this pullback in federal support, there is going to be increased uncertainty as it relates to how healthy the environment is for investing in the U.S.,” says Rhodium Group’s O’Rear.

It still isn’t clear what will happen in the U.S. But more federal support would also help companies test a bigger variety of approaches to the technology. “We don’t know which of these technologies is going to be best at scale—best economic performance, best technical performance, the right kind of projects that communities want to host,” says Erin Burns, executive director of the carbon removal nonprofit Carbon180. As the world blows past 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming, it makes sense to test as many solutions as possible. Without support, some nascent technologies may be lost completely.