Smelting metals and burning coal vaporize small amounts of iron. Some of this iron wafts out of East Asia and into the North Pacific Ocean, where it supercharges phytoplankton growth, a new study found.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, used isotope analysis to estimate that around 39% of the iron in seawater sampled from the North Pacific during the springs of 2016, 2017, and 2019 came from human activities. This added iron is helping phytoplankton consume marine nitrogen faster, causing a long-term northward shift in a North Pacific algal bloom.

“The nitrogen is like a paycheck that they get every year, and when they have more iron, they spend through it faster.”

“The nitrogen is like a paycheck that they get every year, and when they have more iron, they spend through it faster,” said the study’s first author, Nick Hawco, a marine geochemist at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

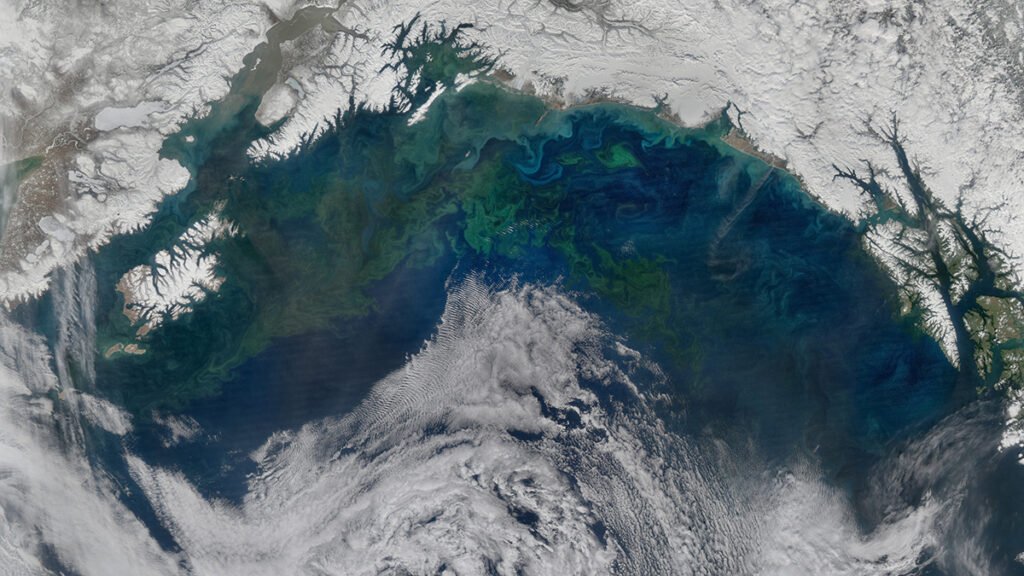

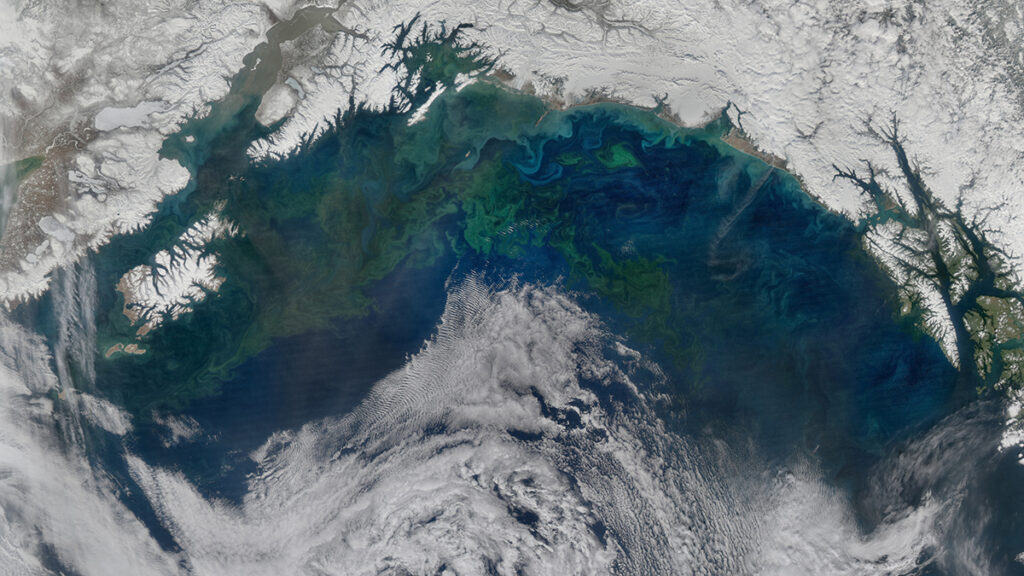

Strong winds churn the waters of the North Pacific every winter, lifting nitrogen and other nutrients to the surface. As ocean currents carry the nutrients south toward a region of mixing gyres called the North Pacific Transition Zone, they fuel a phytoplankton bloom that extends from California to Japan. Tuna, humpback whales, and other sea creatures come to feast on the animals supported by the phytoplankton.

Over the spring and summer, the phytoplankton exhaust the nutrients brought south by currents. This depletion causes the southern extent of the bloom, called the transition zone chlorophyll front, to shift north each year, toward the nutrient-rich subarctic.

Have Iron, Will Travel

Hawco and his colleagues studied the metabolisms of phytoplankton captured from the North Pacific and found signs of iron deficiency. Iron is a limiting factor for phytoplankton growth in the region, the authors argued.

Though desert dust carried long distances by winds historically brought iron to the North Pacific, previous research has shown that industrial activities in East Asia—especially burning coal and melting metals—are a new and growing source of iron.

Between 1998 and 2022, steel production in China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan quadrupled, and coal use more than tripled, according to data from the Global Carbon Project and the World Steel Association. During the same period, the southern edge of the bloom in April shifted north by about 325 miles (520 kilometers), according to satellite measurements of chlorophyll.

“This extra iron is leading to the nitrogen being drawn down earlier in the season, and it’s pushing these waters that eventually become nitrogen limited further to the north.”

In the northern parts of the phytoplankton bloom, chlorophyll concentrations increased, suggesting that the added iron is driving a more intense bloom, according to the authors. As a consequence, the southern edge of the bloom does not reach as far south during the spring, Hawco said. The nutrients that used to fuel it are likely being consumed by the more intense bloom up north, he said.

“This extra iron is leading to the nitrogen being drawn down earlier in the season, and it’s pushing these waters that eventually become nitrogen limited further to the north,” said Peter Sedwick, a chemical oceanographer at Old Dominion University in Virginia who was not involved in the study.

Northward movement of the bloom could have wide-ranging effects. Because the ecosystem supports abundant marine life, many anglers from Hawaii travel there to fish, Hawco said. As it shifts north, that trip is becoming longer and more expensive, he said.

In addition, research suggests that climate change will reduce the amount of nutrients brought from the depths to the surface of the North Pacific. That will reduce the supply of nutrients brought south by currents, causing the southern extent of the bloom to move even farther north, Hawco and his colleagues said. Iron emissions and climate change are having synergistic effects on the transition zone chlorophyll front, they concluded.

Further research is needed to understand the impacts of this extra metal. The phytoplankton bloom sucks up carbon and helps maintain the balance of carbon dioxide between the ocean and the atmosphere, Sedwick said. Any change to the ecosystem could alter that balance, he added.

—Mark DeGraff (@markr4nger.bsky.social), Science Writer

Citation: DeGraff, M. (2025), Iron emissions are shifting a North Pacific plankton bloom, Eos, 106, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025EO250286. Published on 6 August 2025.

Text © 2025. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.