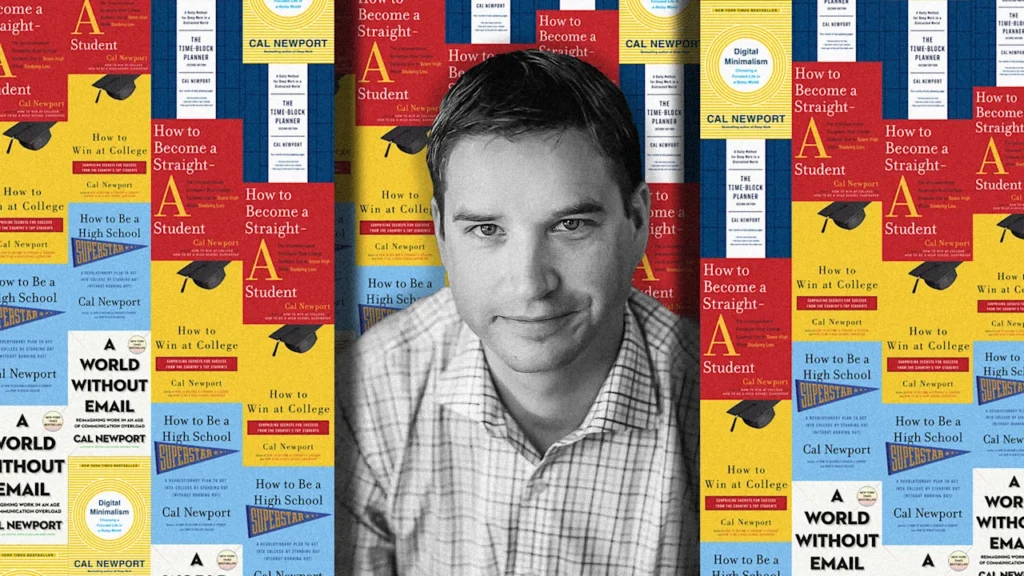

Much of author and Georgetown University computer science professor Cal Newport’s work is about preparation. His books Deep Work and Slow Productivity, among others, make the argument for intention around productivity, creativity, collaboration, innovation, rest, reflection, and recovery.

In fact, Newport’s literary focus is to figure out the best circumstances and cadence for perpetuating creativity. Thatʻs what allows him to do his own writing, maintain his coursework, and generally feel available for new ideas.

Heʻs cultivated an “empire of ideas,” he says, which have helped him sell more than 1.5 million copies of Deep Work alone. It’s also why much of what Newport writes about is so resonant for CEOs and college students alike.

Even scheduling a call with Newport required a purposeful balance of timing. In the summer for a few weeks, Newport flees his home base in the Maryland suburbs of Washington D.C., to New England, where he writes, enjoys quiet, brainstorms, and spends more time in nature and with his family. I caught him one morning while he was in Vermont, post camp drop-off, baseball cap on, in full summer mode.

My day is very seasonal. I believe in having variation throughout the year. The summertime: This is a period thatʻs very idea-focused. In the summer, we go up north. My summer schedule prioritizes two things: long stretches for deep work (typically dedicated to writing), and relief from a busy calendar requiring me to jump rapidly between meetings and calls.

To accomplish this, I try to dedicate every weekday morning, until lunch time, to uninterrupted writing. On Tuesday through Thursday, I’ll schedule meetings, interviews, and other appointments in the afternoon, but I leave Monday and Fridays, if possible, completely devoid of appointments, so I can ease back into the work week more gradually and have longer periods of deep work. These are, at best, targets I hope to hit, but often fall short.

When I get to a busy part of the school year, during a semester I’m teaching or taking care of administrative responsibilities, I try and keep the mornings free for ideas and writing, and know from midday to afternoon I’m teaching class or in meetings.

To think and write: It’s the only thing I want in life. To me, it’s the most precious resource. What I do for a living is generate ideas. That is my top priority. It’s what puts food on the table. That is No. 1: an empire of ideas. The spinning of a good idea; one that captures attention and generates positive impact—I’m building a craft to express ideas. The core hardest talent is ideas training. The secondary skills are to convey those ideas.

The sense that temporarily slowing down requires permission, or is somehow negative, comes from our culture’s embrace of “pseudo-productivity.” This is a term I introduced in my book Slow Productivity that describes the common heuristic of using visible activity as a proxy for useful effort.

We fall back on pseudo-productivity because it’s a shortcut for evaluating people that’s much easier than actually trying to understand what they are doing and why it’s useful. In a culture of pseudo-productivity, any move toward slowing down is read as unproductive and suspicious. The problem is that this measure is deeply flawed. In cognitive work, visible activity can be a poor predictor of how much value someone is actually producing in the long term.

I was a good writer growing up and a precocious reader. I thought writing was hard, though, and being in computers made more sense to me. I went to college to study computer science and started writing in college. I sold my first book after my junior year, and that’s where I said, “I’m going to grad school; it’s flexible enough that I can be writing at the same time.” In fact, I wrote a New York Times op-ed about how I made that career decision. I knew at that point I was going to write and be a professor. I had a job offer in the tech industry, but I knew I wouldn’t be able to write as much as I wanted.

I love movies. Studying movies and trying to get into the details of how a particular movie was made and what makes it a classic . . . I find it a kind of creativity cross-training. When you’re learning about a director none of those stresses are there. I can feel how hard that would have been. It’s all abstract because it’s not in my field. I get a lot of benefit from studying other creative fields. You can operate creative risks. You can think about the writing process and editing process.

I read all of the time; it’s an influx of raw material. I try to read five books a month as a general commitment to cognitive fitness. I mainly read nonfiction as it’s more directly useful to what I do as a writer. I often find inspiration in biographies of professional thinkers and creatives; you gain insight into their process. Just this morning, for example, I finished reading Alec Nevala-Lee’s biography of the Nobel Prize-winning physicist and polymath Luis Alvarez. It had some great material about how Alvarez sifted through potential ideas to find the few that might work.

When you create ideas for a living, you’re looking for what sticks. I don’t use complicated idea tracking systems. I have notebooks. There are a lot of opportunities to try ideas out on the fly. You get a sense that it connects or seems interesting. If there’s a spine tingle, that’s a good one. I think, “There’s something here.”

For idea generation, I’ve got to be walking in nature. That’s by far my 10x. I have to be moving. I can clarify my thoughts better when Iʻm moving. I don’t want extraneous stimulation. If Iʻm working on a book chapter, I’ll drive over to the nearest park—Rock Creek Park or whatever trail is nearby. For writing, though, I’ve got to be quiet. I don’t write with music.

I have multiple offices. I have my podcast studio office/creative playhouse here. I have a library at my house, which we separate from the home office. There is no technology in my library. I have a small upstairs office where you go to, like, pay taxes. The library is analog. There’s a record player, a curated book collection in there. We had our desk custom made by a company in Maine. I have spent my entire adult life in academic libraries so I created a library just for writing.

I like to test out new ideas on my newsletter and podcast to see if they have legs. This is partially about receiving audience feedback, but also partially about just seeing how I feel about the idea once I’ve had a chance to stretch it out and fill in the details. I have a pretty good sense, honed through experience, about what ideas in this seem promising and which are fool’s gold.