There are moments when a single policy proposal reveals the full machinations behind it. The Trump administration’s recent attempt to dramatically expand what foreign visitors must disclose before entering the United States is one of those moments. According to the Guardian, visitors from 42 Visa Waiver countries may soon be required to surrender five years of social media history, 10 years of email addresses, all phone numbers used over the past five years, as well as facial, fingerprint, DNA, and iris biometrics. They would also need to report the names, addresses, and birthplaces of their children and other family members. These requirements apply to ostensibly close US allies, including the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Australia, and Japan. Since 1986, citizens of Visa Waiver countries have been able to stay in the United States for 90 days or less without a visa.

This isn’t just bureaucratic overreach. It’s a signal, one with very real consequences for the art market.

To be clear, the implications of this proposal by US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) stretch across civil liberties, privacy, free speech, diplomacy, and global travel, echoing the agency’s broader repressive and anti-immigrant policies.

Jeramie D. Scott is senior counsel and director of the Surveillance Oversight Program at the Electronic Privacy Information Center, one of several organizations opposed to this regulation.

“DHS has never found social media screening to be good at vetting travelers or immigrants,” Scott told me. “Indeed, a pilot program run by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services that experimented with social media screening for immigration vetting found it borderline useless. What social media vetting is good at is threatening rights to expression, association, and privacy.”

The impact on the art market deserves distinct attention. Markets depend on movement — of people, objects, money, and ideas. When you make movement difficult, the system adapts. Introduce friction, and the people you depend on change their behavior, sometimes drastically.

In 2024, the United States accounted for roughly 43% of global art market sales, according to the recent UBS and Art Basel Survey of Global Collecting. The countries whose citizens would be subject to these new requirements collectively represent 34% of global sales. These are the collectors, gallerists, curators, scholars, and artists who animate the ecosystem. They’re not peripheral. They’re essential.

If entering the United States suddenly requires surrendering your digital life and your family’s private information, how long before people simply choose not to come?

We’ve already seen that when governments implement barriers to travel and commerce, art collectors simply take their business elsewhere. Before Brexit was finalized in 2020, London was a dominant, unquestioned art-market center in Europe. Political uncertainty, customs barriers, and shifting regulations didn’t collapse the UK’s art market, but they did something more subtle and damaging: They made London inconvenient.

Within a few years, Paris surged. Paris+ (now Art Basel Paris) replaced Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain and became a major fair. Galleries like Gagosian, Zwirner, Mariane Ibrahim, and White Cube expanded their Paris footprints. Auction houses shifted marquee sales to the Continent. Collectors redirected their travel patterns. And what began as policy turbulence became a structural realignment.

The lesson is straightforward: When you introduce friction, the market routes around you. If US entry becomes onerous, alternatives are ready and waiting: China, already the world’s second-largest art market; Hong Kong and Singapore, both actively building cultural-financial ecosystems; India, where wealth and institutions in Delhi and Mumbai are growing fast; the Gulf states, especially Qatar and the UAE, investing heavily in museums and fairs; and African hubs, including Nigeria, Ghana, and South Africa, which have become increasingly influential nodes in the global art conversation.

These regions don’t need to replace the United States outright. They only need to absorb the traffic the US pushes away. And like all markets, the art market doesn’t shift through dramatic declarations. It shifts through countless small decisions by people responding to new constraints.

The consequences won’t end at the marketplace. If international artists, curators, and scholars balk at these requirements, the ripple effects will extend to the entire infrastructure of art and culture in the United States.

Artist residencies, co-curated exhibitions, and research partnerships are all enriched by international collaborations and connections. When travel feels risky or invasive, participation declines. And faced with intrusive data demands or visa denials, artists may choose to apply to MFA or residency programs in Paris, London, or Mexico City instead.

Exhibitions will become harder to mount: International loans often require conservators, registrars, and couriers to travel with the work. If those individuals refuse, institutions abroad will be forced to reconsider loaning pieces to US museums.

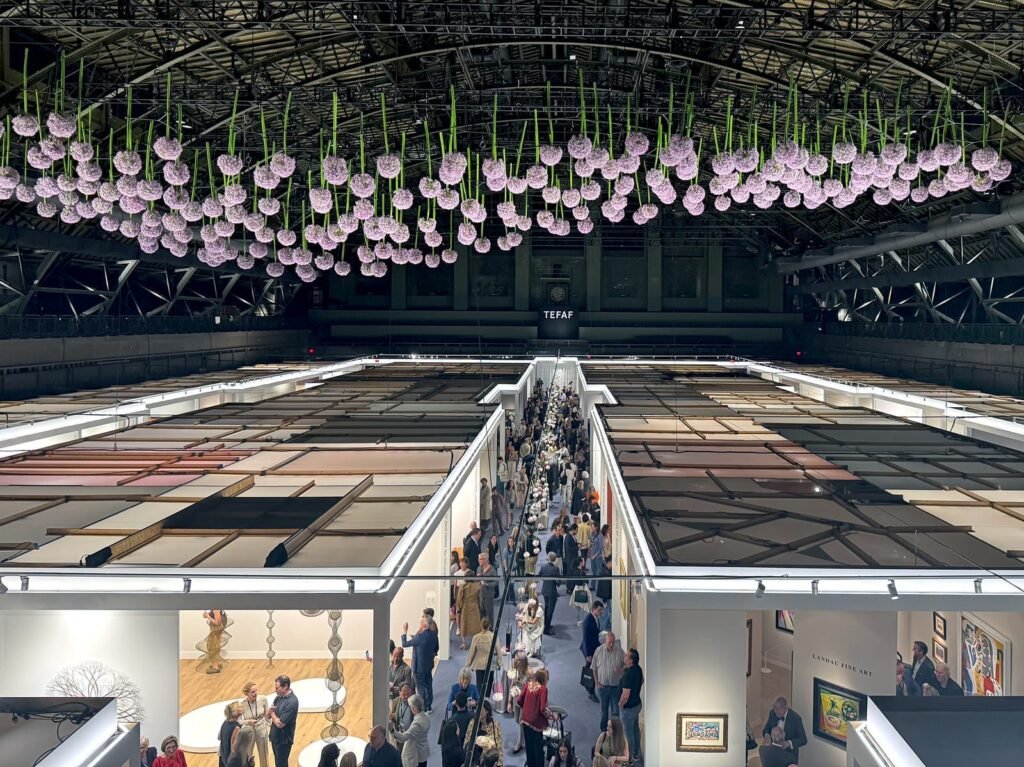

Fairs will lose their wealthiest buyers. Frieze New York, The Armory Show, and others all depend on international collectors. If those collectors avoid the US, the economic foundation of these fairs weakens quickly.

None of this is hypothetical. Brexit showed how quickly a major art-market hub can be sidelined. The US is not immune to the same dynamics.

As someone who has led two New York City cultural institutions, I learned how fragile ecosystems become when trust erodes, whether that erosion comes from funders, partners, or communities. Once trust is lost, rebuilding it requires time, attention, and sustained effort. The US art market is now testing the limits of international trust.

For decades, the United States benefited from a set of assumptions: that it is the gravitational center of the art world, that people will always come, and that the system will bend to accommodate American dominance. But dominance isn’t a birthright. It’s the result of being the easiest, most stable, most predictable place to transact. This proposal threatens the very qualities that make the US competitive in the art market.

The public comment window on this rule ends on February 9. Comments can be submitted to CBP_PRA@cbp.dhs.gov, with “OMB Control Number 1651-0111” in the subject line. Unsurprisingly, the agency is only asking for comments on technical and administrative aspects of the proposal, not the broader cultural implications. Real influence will need to come from elected officials who understand what’s at stake. If these requirements take effect, the global art market will do what it has always done in the face of constraint: It will adapt. And if history is any guide, it will adapt by moving away from the United States.

The real question — the one the US art market, museums, and policymakers all need to confront — is whether we’re prepared for that shift, or whether we will, once again, learn the hard way that the world can get along just fine without us.