As Israel’s assault on Gaza rages on and residences across the 140-square-mile strip continue to be bombed and razed to the ground, a museum installation in New York City combines journalism, oral history, art, and architecture to pay an immensely personal tribute to homes destroyed in Palestine, Iraq, and Syria by weapons manufactured in the United States.

Visitors at the Patterns of Life exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum are invited to look into the former homes of three families —one in Gaza, a second in Mosul, Iraq, and a third in Manbij, Syria — each demolished by military operations over the past decade. The show is one of the centerpieces of this year’s Smithsonian Design Triennial, titled Making Home and on view through August 10 at the Manhattan museum.

Among the three civilian residences in the exhibition is Basim Razzo’s former family home in Mosul, which was reduced to rubble by an airstrike in September 2015 after the American-led coalition fighting the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria wrongly identified it as a car-bomb factory. Razzo lost his wife, daughter, nephew, and brother in the strikes on their side-by-side homes in the city. “My house was my kingdom,” Razzo told Hyperallergic. Upon walking into the Cooper Hewitt show, which he visited last November, Razzo recognized the distinct marble entrance and large windows of his former home.

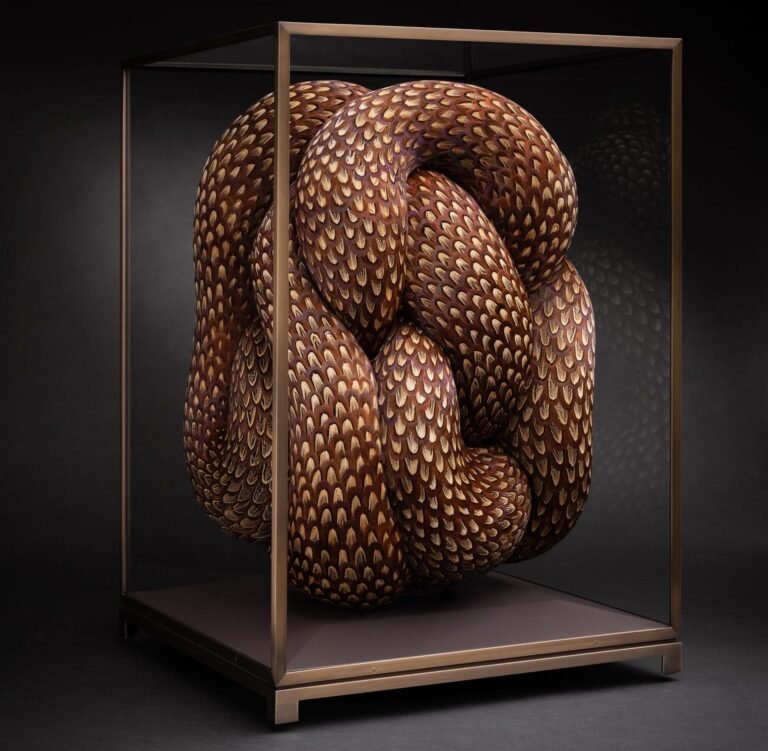

Through interviews with the survivors of the airstrikes, images and videos they provided of their homes, and archival satellite imagery, data journalist Mona Chalabi and visual investigators at SITU Research collaborated to create architectural models of the homes that were. The installations were then furnished with miniature models of household objects replicating material memories from the lost homes: family paintings on the wall, intergenerational crafts, and curtains that a husband was often reminded to clean by his wife.

“These places are represented in the Western media through the lens of destruction, rubble, and tragedy,” Gauri Bahuguna, a visual investigator and open source researcher at SITU who worked on the project, told Hyperallergic. “But these were homes full of very normal lives. That very mundane core humanity gets washed out in most representations.”

When he was first approached about the project, Razzo, whose own tragic experience made him become an advocate for the rights of other airstrike survivors and victims, said he was excited that the show “would be something that Americans could see — how the house was, what the airstrikes did, the loss of life and property.” For Chalabi, a British journalist of Iraqi descent, including Razzo’s home in the exhibition was an effort to prevent the United States’s war on Iraq from being forgotten.

Upon viewing the exhibition, Razzo was struck by the attention to detail that Chalabi and her team had managed to achieve. He said that many of the elements of his home were displayed in a near-identical fashion in the model, such as a small radio from the 1950s in his bedroom, on a dresser that had originally adorned his parents’ home. He praised the striking similarity of the signature green chandelier, a centerpiece of his former home, hanging from the ceiling of the model. Razzo laughed, recalling the bi-annual cleaning routine that he and his wife, Mayada, would undertake.

The process adopted by the creators of the exhibition merged long-form qualitative interviews and open source intelligence (OSINT) methodologies, such as inspecting satellite imagery to recreate the exteriors of the models as accurately as possible, both in terms of the interiors and the overall structure of the homes.

The objects within the homes were portrayed through illustrations by Chalabi on a semi-transparent silk fabric. “The memories have a kind of fragility. They live on in the survivors, and they’re able to relate them to us, but there is something that’s lost,” Chalabi told Hyperallergic. “For me, one way to capture that was by using a kind of sheer material, something that can kind of be seen through, that has a porous quality.”

“You cannot erase memories,” said Mohammed Osman, whose home in Manbij, Syria, was destroyed in an airstrike by the US-led coalition in 2016, and is one of the three homes modeled in the exhibition. What touched him most was the display of the hand-crafted piece of woodwork built by his father that sat in the middle of the living room table. He recalled having spotted it lying in the rubble after his home was destroyed. The model of Osman’s residence also included colorful family portraits and a painting of Islamic verses.

The experience of participating in this project, he said, allowed him to reminisce about the little details that made his house a home. He remarked that his treasured bookshelf is displayed in the installation, and recalled how each of the shelves had housed different areas of Arab and Islamic literature he had collected over time.

The artists attempted to recreate some of the smells of the homes, too. Chalabi said that Razzo, for example, had spoken about how he had planted roses all around his house, “and so you could smell flowers all the time.” Osman recalled that when he opened the door of his house, he would be greeted by a fragrance of jasmine. Chalabi said they used scented oils on the silk to evoke these olfactory memories.

A third home, that of a mother and her son in Gaza (whose identities were left unnamed to ensure their safety), represents the thousands of Palestinian homes destroyed by Israel since October 7, 2023 — 92% of housing units in Gaza, according to a Doctors Without Borders report from January. Illustrating that reality was just as important to Chalabi, Bahuguna, and their team.

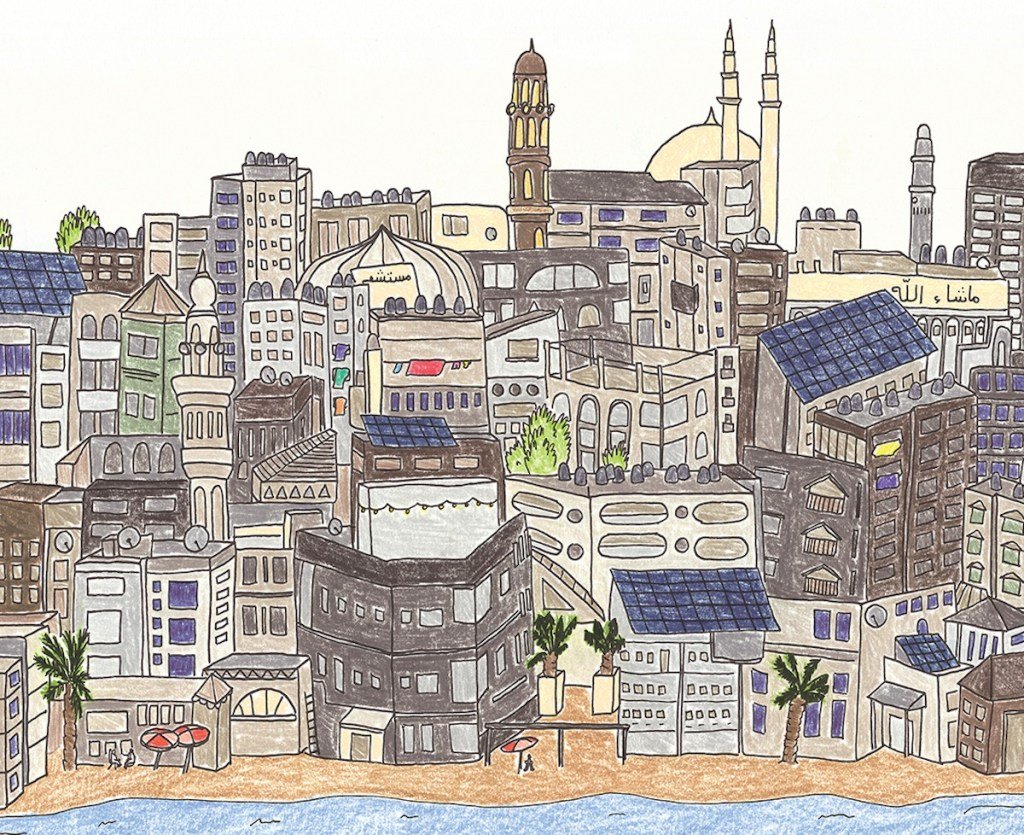

Chalabi’s sketches of the towns — Gaza, Mosul, Manbij — adorn the walls surrounding the exhibition. Alongside a drawing of Mosul featuring the Tigris river that runs through the city, a piece of handwritten text reads, “65% of homes in Mosul have been damaged or destroyed, including Basim’s. Source: Minority Rights Group, January 2020.” Similar details accompany the depictions of Gaza and Manbij, recalling Chalabi’s recognizable, award-winning visualizations of eye-opening statistics. The buildings painted in a lighter shade on the walls represent the proportion of homes destroyed in those cities.

Yet, despite the adherence to hard facts in the numbers on the walls and the detailing of the models, Chalabi took a few artistic liberties with the homes themselves. “It’s a piece of art as well, and there were assumptions I was making,” she said. For instance, in the model of Razzo’s home, Chalabi added a little framed piece of calligraphy of his daughter’s name, Tuqa, as a way to commemorate her.

“The exhibition is a testament to how much homes matter, but also, to honor the memories and people that lived in them,” Chalabi said.