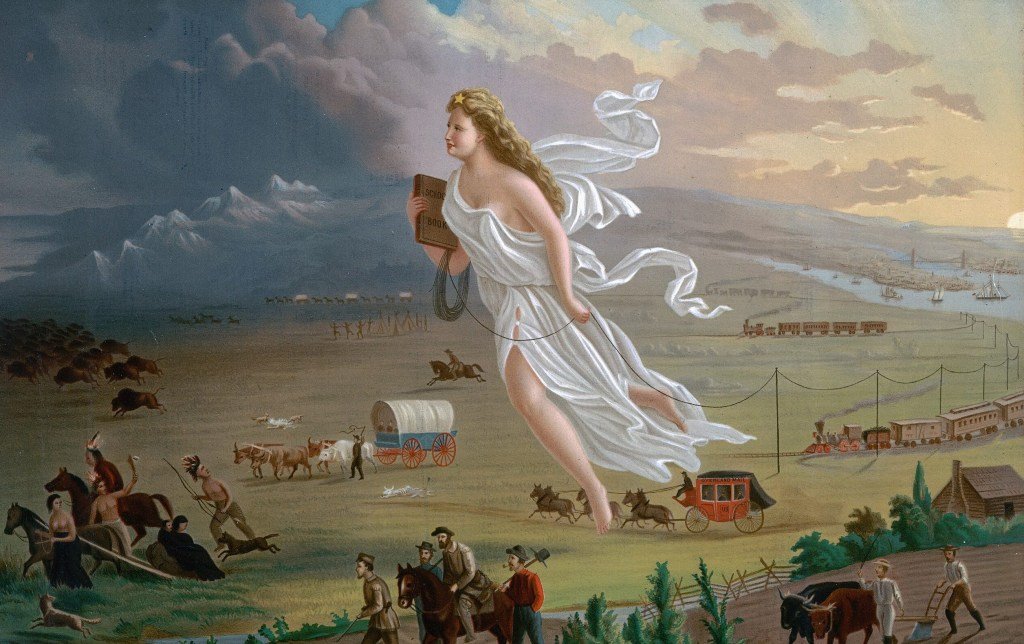

Prussian painter John Gast’s 1872 composition “American Progress,” now held by the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, isn’t very good. An unsubtle celebration of Manifest Destiny, the 19th-century American mania for westward expansion at the expense of Indigenous peoples, Gast’s painting features a zaftig blonde-haired and blue-eyed avatar of Progress aloft in the sky, moving from a civilized east of ships, locomotives, and telegraph lines towards a wild west. White settlers in Conestoga wagons and stagecoaches follow her; a group of horse-bound Indigenous people flees into the finality of darkness towards the dusky horizon behind her. Beyond the horrific politics, the perspective is amateurish and the sense of color awkward, not to mention that the wonky proportions of the eponymous toga-clad incarnation of Progress herself are more a signifier of beauty than an actual example of it. Considering the painting’s relative lack of technical skill and its deserved disregard within the American artistic canon, there must be some reason beyond aesthetics that, on July 23, the social media directors at the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) saw fit to post the painting on outlets such as Facebook along with the caption: “A Heritage to be proud of, a Homeland worth Defending.”

The same year that Gast finished “American Progress,” a contingent of 130 soldiers of the 5th Calvary Regiment arrived at Skeleton Cave in Arizona’s Salt River Canyon, where a group of Yavapai people had been sheltering. In under an hour, the army slaughtered almost a hundred of the Yavapai, including many women and children. Within the ugly history of the so-called American Indian Wars — from the Puritans perpetrating what a contemporaneous historian called a “great and notable slaughter” of the Nipmuc Indigenous people in Turner’s Falls, Massachusetts in 1676 to local White settlers “consummat[ing] a most inhuman slaughter” against the Nasomah people in Randolph, Oregon in 1854 — the bloody events at Skeleton Cave can fade into the background. For while the stylized Indigenous people of Gast’s composition are rendered in red and black paint on canvas, the actual story of genocide on the frontier was colored in spilled blood and burnt flesh. As Lenore A. Stiffarm and Phil Lane Jr. maintain in their essay in The State of Native America: Genocide, Colonization, and Resistance (1992), “there can be no more monumental example of sustained genocide … anywhere in the annals of human history.” Most references and considerations of Gast’s painting are illustrative of Stiffarm’s point — the majority of scholars would admit that “American Progress” is an ugly bit of colonial propaganda, making the DHS’s extolling of the painting even more ominous.

The social media imbroglio around Gast’s painting isn’t the only controversy that DHS has generated in recent weeks. On July 14, it posted the schmaltzy “A Prayer for a New Life” (2020) by contemporary painter Morgan Weistling, under the incorrect and chilling title “A New Life in a New Land.” It is a picture of a young settler couple on the frontier, surrounded by provisions within their Conestoga wagon, cradling their newborn (White) infant as a craggy western vista absent of any pesky Indigenous people yawns out in the background. DHS’s caption of Weistling’s painting reads “Remember your Homeland’s Heritage”; the unusual double-H capitalization led some commentators to argue that the post might be a dog whistle for the White supremacist code of “HH” for “Heil Hitler.” Whether or not that aspect of the post was intentional, its presentation of “New Life in a New Land” itself is meant to be understood in the most obvious way. Whatever group of people are manning the social media feeds at DHS (and there are more than enough creepy weirdos gestated in the fever-dream of online alt-right meme speak who fit the profile) the message is clear: Genocide of Indigenous people was no big deal, contemporary (White) Americans need not feel ashamed about Manifest Destiny, and Trump’s DHS is more than willing to enact similar policies today.

To Weistling’s credit, he has emphasized that the post was made without his approval, while the estate of Thomas Kinkade, whose work was used in a similar post, has also disavowed the DHS’s appropriation of his work. Whatever the former’s intentions may have been, however, his painting is also not good — but it is interesting, in part because its operative mode concerns a violence of invisibility. Unlike Gast’s painting, with its fleeing Indigenous warriors, this idealized Western frontier is truly a virgin land, absent of people; colonists may thus acquire it without guilt.

“A Prayer for a New Life” evokes, albeit in a less grandiose manner, German-American painter Emanuel Leutze’s massive patriotic mural “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way,” which was unveiled in 1861 in Congress. In that composition, the Western frontier is settled by hardy men in coonskin caps and women in bonnets traveling on Conestoga wagons through a rugged and empty landscape where there are no Indigenous people to be found. Three years after Leutze’s work was installed, the 3rd Colorado Cavalry may have murdered as many as 600 Cheyenne and Arapaho people, the vast majority of them women and children. In a moment of devastating irony, during congressional testimony about the massacre in 1864, both witnesses and perpetrators would have walked by “Westward the Court of Empire Takes Its Way” as they entered the chamber. During said testimony, a witness named John Smith confessed to seeing “women cut all to pieces … with knives; scalped; their brains knocked out,” while reporter Robert Bent of the New York Tribune wrote that he saw a woman “cut open, with an unborn child lying by her side,” while other journalists recorded Indigenous children being used for target practice or severed body parts being collected by soldiers to be worn as jewelry. The House committee condemned the soldiers, but no charges were brought. Until recently, some memorials still had the temerity to call the Sand Creek Massacre a “battle.”

Mere decades later, American Manifest Destiny would offer eerie parallels to Nazi Lebensraum across the Atlantic. James Q. Whitman, in Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (2017), notes that despite Nazi misgivings about supposed Yankee cultural decadence, “in Mein Kampf Hitler praised America as nothing less than ‘the one state’ that had made progress toward the creation of a healthy racist order of the kind the Nuremberg Laws were intended to establish”; indeed, the fascist code was in part inspired by Jim Crow and anti-Indigenous legislation. Hitler himself once said, “One thing the Americans have and which we lack … is the sense of vast open spaces.” Timothy D. Snyder quotes that line in Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning (2015), in which he describes how the heretofore relatively middling European colonial power of Germany drew from the American example of genocide against Indigenous people as a model for how Jews, Roma, and Slavs were to be treated in the east. “Where was Germany’s frontier,” writes Snyder, “its Manifest Destiny?” As the Nazis blitzed into eastern Europe during Operation Barbarossa, Snyder argues, they were in part inspired by the exact sort of romanticized rhetoric that one sees in the novels of Karl May, a German who wrote popular Westerns when Hitler was a boy, or indeed in the kind of imagery represented by a Gast or a Leutze.

Or, for that matter, a Werner Peiner. A professor at the Düsseldorf Art Academy and an officially sanctioned painter of the Third Reich, Peiner exulted in the sort of sentimental vistas that recall American 19th-century art of western expansion. “German Soil,” painted in 1940 and now owned by the Museum Würth in Künzelsau, Germany, depicts a Teutonic farmer tilling his fields of orderly wheat, moving towards a blackening horizon in the distance, his fields bathed in an eerie, immanent light. The work’s advocacy for lebensraum is more subtle than an out-and-out propaganda piece, such as the 1939 poster encouraging ethnic Germans to settle in recently conquered areas in Czechoslovakia and Poland, a swastika-emblazoned knight’s shield superimposed over those territories. Rather, as with the violence of invisibility in Leutze’s work, there is a conceit of plausible deniability for Peiner. In composition, the latter is superior to both Gast and Leutze, but he evokes the same feeling of providential ownership over land itself, of the supposed significance of blood and soil. More than just a bucolic pastoral, it should be noted that with the light setting behind the farmer, it seems clear that Peiner’s figure is moving — as the Reich itself did — towards the east.

Nazi art also predictably traded in the enshrinement of the normative family unit as surely as Weistling’s depiction of the settler couple does (or that’s at least the clear ideological intent of the DHS’s posting of the latter). Adolf Wessel, frequently exhibited in the state-sanctioned Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung, does as much in his 1939 “Kalenberg Peasant Family,” which presents three generations of a stolid rural Aryan family: a mother, father, grandmother, and three children who with grim determination stand in for the future of Hitler’s state, the same connection between blood and soil made by the artists of American Manifest Destiny. As the Nazi theorist Richard Walther Darré claimed, the “German soul with its warmth is rooted in its agriculture and in a real sense always grew out of it.” Citizenship is defined thus not by commitments, but by the land itself, or as Vice President JD Vance said at a July 5 speech at the conservative Claremont Institute, citizenship “is not just an idea,” but rather something defined by being from a “particular place with a particular people and a particular set of beliefs and a way of life.”

Indeed, conflations of an (anonymous and invented) individual with the regime frequently took on an erotic cast, as if endorsing the propagation of a defined racial type. Look no further than the exposed leg of Gast’s Progress or Leopold Schmutzler’s circa 1940 “Working Maidens” (held at Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin) wherein four hale and healthy, coquettish and comely Teutonic peasant women walk smiling through a field — which was presented at Munich’s Great German Art Exhibition only a year after German tanks crossed into Poland to expand the “living room” of the nation. Sexualization of White supremacist tropes is increasingly mainstream today, as with the controversial American Eagle ad featuring blonde-haired and blue-eyed actress Sydney Sweeney making a homophonic pun on her “great jeans,” which, even if unintentional, speaks to the way in which fascism has become trendy.

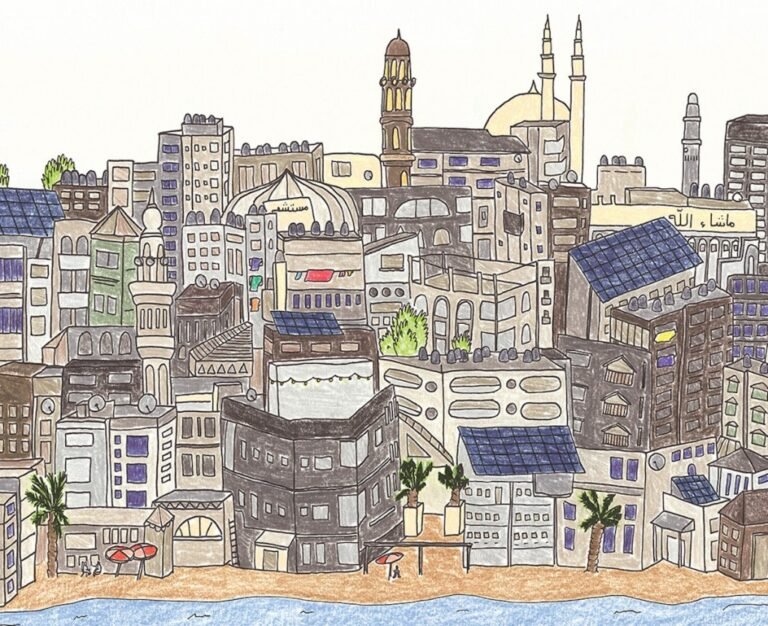

Americans may blanch at comparisons of the multi-century process of genocide of Indigenous people to European examples, even while historian David E. Stannard in American Holocaust: Columbus and the Conquest of the New World (1993) described the former as the “worst human holocaust the world had ever witnessed … consuming the lives of countless tens of millions of people,” but it is an uncomfortable reality. The DHS posts may be hokum and kitsch, pablum and camp, but it also evidences a very dangerous current situation, particularly as the budget for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), already operating several concentration camps throughout the United States, will increase to larger than the militaries of Canada, Turkey, Mexico, Iran, and Spain. This isn’t even to mention the US’s active support of Israel’s current genocide and famine in Gaza.

In such a context, resistance must be as much aesthetic as material. Four years ago, when many pundits thought that Trump’s return was unlikely, Native-American artist Charles Hilliard revised Gast’s “American Progress” in the 2021 composition “Reversing Manifest Destiny.” Here, the incarnation of Liberty has been replaced with the sacred Lakota figure of the White Buffalo Calf Woman, brown-skinned with long, flowing black hair, moving from a bright West towards a pollution-darkened, smoggy east whose horizon is punctuated with belching exhaust, bringing with her Indigenous warriors and bison as the continent’s ecological devastation is erased behind her. A fantasy, of course — there are no easy escapes from our brutal history. But it’s an alternate vision to the future drawn by the twin specters of genocide and ecocide. The possibility of making a better world first necessitates dreaming it.