You think you know Patagonia, the apparel brand beloved by crunchy hikers and finance bros alike. But the company is more than half a century old, and it has taken many unconventional turns to become an icon of sustainable business.

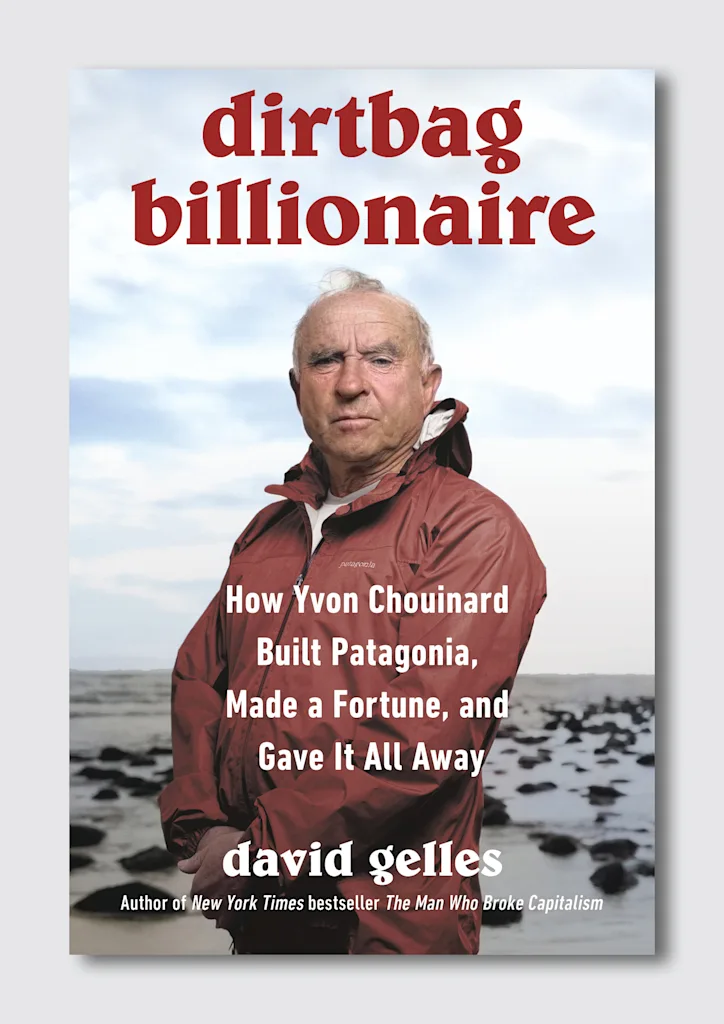

A new book digs into this history, offering lots of untold moments about the company that even die-hard Patagonia fans may not know. In Dirtbag Billionaire: How Yvon Chouinard Built Patagonia, Made a Fortune, and Gave It All Away, author David Gelles provides a behind-the-scenes look at how Patagonia was built. Through in-depth interviews with Chouinard, we learn about the many conflicting pressures the Patagonia founder faced as he tried to create an apparel brand that does more good than harm in the world.

Here are three surprising things that happened along that journey.

Patagonia Once Partnered with the Pentagon

In the 1970s, the U.S. military was one of Patagonia’s biggest fans. It began with climbing gear. Chouinard, an avid rock climber, first came up with the idea of starting his company because he wanted to make better climbing gear. He couldn’t find metal spikes that he liked for wall climbing, or ice axes for ice climbing, so he developed them himself.

When the military got wind of these functional climbing tools, they began buying them for soldiers who would need to scale walls during military missions. In the decades that followed, Patagonia introduced innovative new fabrics that were moisture wicking and thermoregulating. By the 1980s, the military was buying off-the-shelf Patagonia base layers and fleeces for enlisted personnel working in cold climates.

“The [A]rmy’s 3rd Infantry Division was soon handing out full kits of Patagonia off-the-shelf long underwear and dark blue pile suits to its long-range surveillance teams to ward off the cold,” Gelles writes. Then, Patagonia was enlisted to create a custom cold-weather layering system for soldiers.

Today a close partnership between Patagonia and the U.S. military seems odd: Patagonia is associated with hippies and environmentalists, and yet the gear was being used to train soldiers for combat. And indeed, over the years, the brand’s antiwar employees and fans often criticized Patagonia for this collaboration. But Chouinard wasn’t bothered by the complaints, Gelles says, partly because he was a veteran of the Korean War and understood how hard life was for soldiers. In the end, Chouinard argued that Patagonia wasn’t making weapons or ammunition. “Bras don’t kill people,” Chouinard told Gelles. “People kill people.”

Patgonia and Walmart Were Once Unlikely Bedfellows

In 2005, Walmart invited Chouinard to speak to its top executives at its headquarters in Bentonville, Arkansas. Rob Walton, Walmart’s then CEO, had been connected with a sustainability expert who had worked closely with Patagonia, and he was intrigued by how Walmart could potentially be a force for good.

Chouinard, in turn, was intrigued by the invitation: He believed that if he could convince a company of Walmart’s scale to improve its practices, this could create enormous impact. Chouinard and his wife, Malinda, traveled to Arkansas from their home in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, on a private jet sent by Walmart.

In the book, Gelles paints a picture of what happened when Chouinard took the stage wearing a ratty wool jacket with leather elbow patches. He didn’t mince words. He accused Walmart of not using its influence for good. In a striking example, Chouinard pulled out an enormous pair of jeans, designed for a morbidly obese person, with billows of fabric. According to Gelles, Chouinard said, “I have to hand it to you. How do you sell something like this for $8.99? The fabric alone must cost that much!”

Despite the confrontational nature of Chouinard’s talk, Walmart executives were eager to learn more. So they started making regular visits to Patagonia HQ to learn what they could. The two companies collaborated to create the Sustainable Apparel Coalition to develop a common set of standards called the Higg Index for fashion brands to sign on to. But after the index launched, the partnership petered out. Chouinard believed Walmart execs were willing to do a few easy things to improve the company’s supply chain, but not what was required to actually clean up the entirety of that supply chain.

Patagonia accidentally sickened its Boston store employees

In the late 1980s, Patagonia opened a store in Boston. But after a few days in operation, Gelles writes, workers began complaining of headaches—and the symptoms didn’t go away. So Patagonia brought in an expert to see what was going on.

The determination was that the company’s new clothes were covered in formaldehyde. As workers unboxed the merchandise, they were breathing in toxic fumes. (Formaldehyde is a carcinogen.) The expert recommended a better HVAC system as a solution. Instead, Chouinard wanted to rid his product of toxic chemical treatments.

Over a long process aimed at getting rid of toxins that harm both people and the planet throughout the supply chain, Patagonia eventually landed on cotton farms that often use large amounts of pesticides. Cancer rates in regions where cotton is grown were 10 times higher than normal. So Chouinard asked his team to explore sourcing organic cotton. By the mid-1990s, Patagonia was among the first apparel brands to use organic cotton.

By the time Walmart’s executives partnered with Patagonia in the early 2000s, they too became interested in organic cotton, and began placing large orders with farmers. Some Patagonia employees worried that the relationship would harm the former’s business, since organic cotton was part of what differentiated Patagonia from Walmart and other competitors. But over time, Patagonia grew into its leadership role in the apparel industry and realized that when other brands followed its lead, it was a win for all.