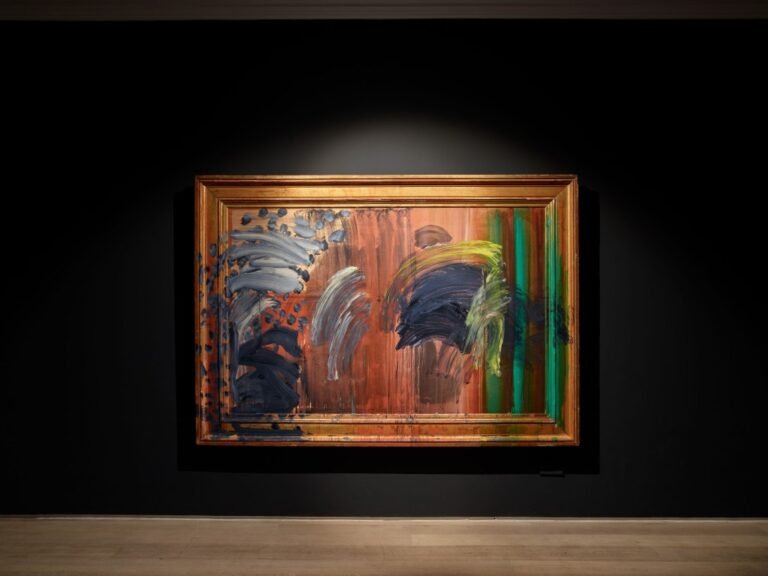

LONDON — An exquisite rhythm rolls across the sheer mass of Emily Kam Kngwarray’s paintings, produced in prolific bursts of creativity between 1980 and 1996, the last decade and a half of her life. As she worked at the forefront of a movement that sought to translate millennia-old Aboriginal cultural traditions onto media such as acrylic, canvas, and batik, much of her oeuvre is marked by a strong visual cohesion. Colorful fields of dots and linear motifs in earthy tones proliferate across the entirety of each picture plane, often covering the edges of the canvases, creating an impression of an expansiveness that seems to incorporate both microcosm and macrocosm, landscape and human, ancestral time and contemporary pressures.

Kngwarray was an Anmatyerr woman born in Alhalker, in what is now known as the Northern Territory of Australia. An important Elder within her community, she is credited with breaking down the distinctions between fine art, craft, and cultural practice, gaining international recognition for her contribution to contemporary art. Her paintings and batik silks are inextricably rooted in the lands on which she was born, which in her earliest years were untouched by White settlers. However, when she was a child, they colonized Alhalker, and their introduction of sheep, cattle, and fences irrevocably changed her people’s Country.

This concept of “Country” is key to understanding Kngwarray’s work and the culture in which she developed her practice. As an explanatory wall text puts it, “For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, the concept … encompasses the lands, skies and waters to which they are deeply connected, over countless generations. Country is a shared place of spiritual, social and geographical origins.” In Kngwarray’s paintings, such as “Ankerr (Emu)” (1989), this manifests as a map-like depiction of emu footprints emerging from a web of patterns and dots, charting the routes taken by the birds between underground water sources.

Kngwarray’s work also draws closely on Dreamings: ancestral beings who manifest in the plants, animals, and natural phenomena of Country. Dreamings are intrinsic to Kngwarray’s worldview and practice, with a focus on animals and plants which are special to her, including the ankerr (emu) and anwerlarr (pencil yam). Yet in Western contexts, such traditions have too often been exoticized, flattening their complexity and cultural significance. The Tate show doesn’t openly refer to previous Western cultural or curatorial practices in relation to art by Aboriginal peoples, but it does take pains to explicate the respectful approach used throughout this show, using terms like Country and Dreaming without romanticization, and applying spellings of Anmatyerr words deemed appropriate by Kngwarray’s family and community. In addition, the exhibition texts use Aboriginal place names alongside English ones, as well as Anmatyerr words for the plants and animals Kngwarray depicts.

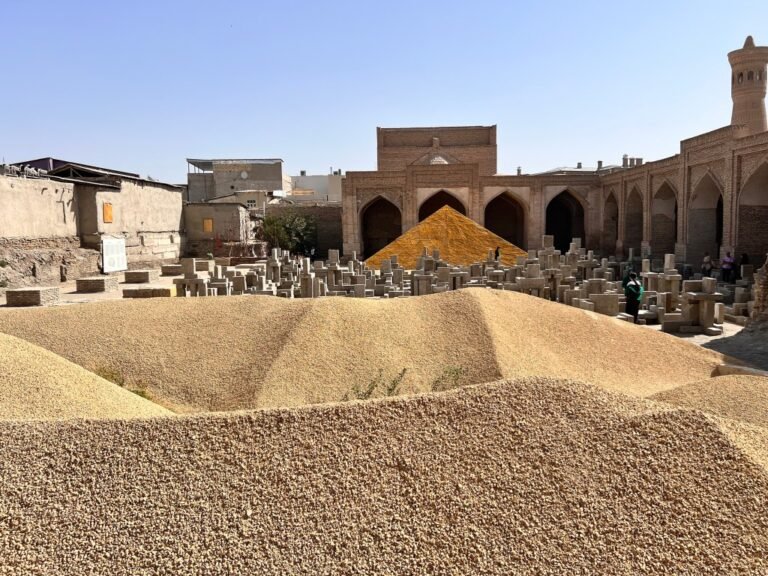

Some of Kngwarray’s paintings relate to Awely, women’s ceremonies celebrating certain animals or plants, in which they grind pigments to paint dots and patterns on each other’s bodies. Included in the exhibition is a video in which Kngwarray’s family members perform one such ceremony; they also contributed to the curating and textual interpretation of the exhibition. The show draws convincing parallels between these rituals and the texture, techniques, and patterning of some of the large-scale works displayed nearby, such as “Alhalker – My Country” (1992), a heavily layered tall panel dotted with shades of rust and ocher. Swirling patterns emerge and fade before the viewer’s eyes, recalling the cyclical verses of ceremonial songs, or the tradition of temporary sand drawings made by women to tell stories.

The corridor connecting Kngwarray’s earlier works with some of her later experiments is wallpapered with an aerial photograph of Alhalker Country, which at first glance could be a blown-up reproduction of one of Kngwarray’s paintings. The next gallery features “The Alhalker Suite” (1993), a huge composition made up of 22 panels offering a similar aerial perspective on the landscape. This work moves away from her previous characteristic earthy palette, instead embracing a collection of red, purple, and blue tones to capture changing light and seasonal transformation. Rejecting the Western art historical (and implicitly colonial) tenet of the single viewpoint, this work uses iteration and patterning to explore the multiplicitous identities of a place, drawing on a notion of layering that is key to her entire oeuvre.

While many Western viewers might dismiss subjects like emus, yams, or seeds as trivial, Kngwarray and her kinswomen approach these beings with profound seriousness. Through the dedication with which she meticulously renders layer upon layer of these motifs, she reveals an alternative vision of art that centers the nonhuman ecologies at the heart of Aboriginal life, spiritual practice, and creative culture. An intimate knowledge of the growth cycles of plants and the movements of animals is essential for survival on Country, while the concept of the Dreaming suggests an essential ongoing continuum between human and nonhuman inhabitants of these places. Kngwarray’s work encourages us to take these worldviews and ecologies seriously too; in an era of climate breakdown and extinction, our future may depend on it.

Emily Kam Kngwarray continues at Tate Modern (Bankside, London), through January 11, 2026. The exhibition was curated by Kelli Cole.