If you sit on the terraced steps at the newly-rebuilt Wagner Park on the Manhattan waterfront, looking out at the Statue of Liberty, you probably won’t know that there’s an 18-foot-tall flood wall hidden under your feet.

The small park, which just opened after an 18-month renovation, is one piece of a larger, $1.7 billion system of flood protection being installed in New York City.

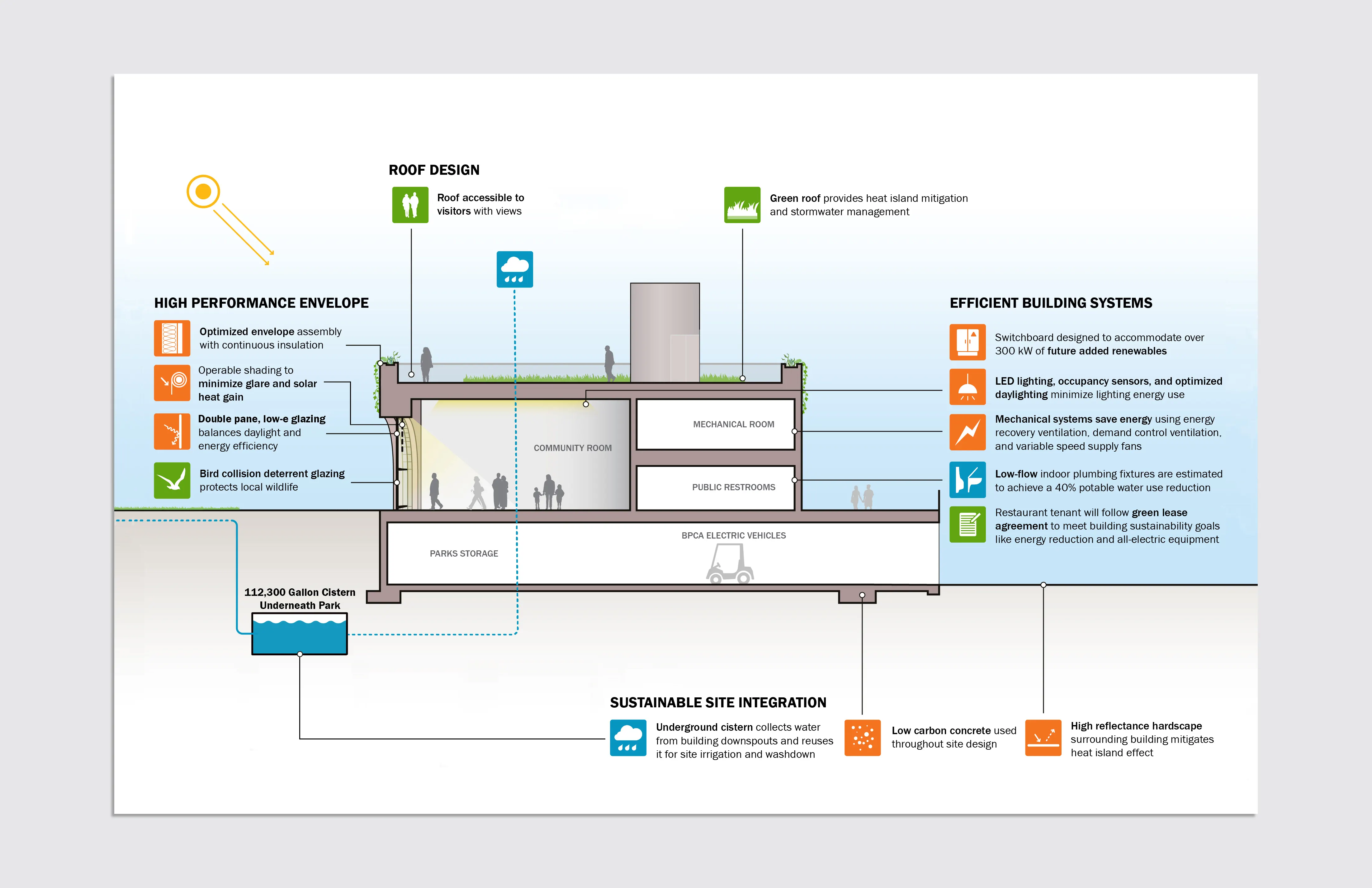

Most of the park now sits around 10 feet higher than it did in the past, with the hidden wall high enough to hold back water in a storm surge. Under the central lawn, a 63,000-gallon stormwater cistern holds rain in heavy storms, then recycles the water to irrigate the park. On the other side of the wall, near the Hudson River, rain flows through gardens and into an infiltration system that releases it slowly to help avoid floods.

“You can engineer these solutions with large floodwalls everywhere,” says Raju Mann, president and CEO of Battery Park City Authority, the public benefit corporation that manages urban planning in the area. “But here, we took a more careful approach. How do we have a great open space that also has flood protection in it—not how do we just build a flood protection project?”

From the beginning, the design team knew that they wanted to avoid exposing the floodwall as much as possible. In a few spots in the park, tunnels underground meant that it wasn’t possible to go down to the bedrock, and the wall is exposed. But most of it is completely hidden. In other parts of the park, flood gates integrated into pathways can pop up in an emergency, but otherwise aren’t noticeable.

“It’s a beautiful waterfront,” says Gonzalo Cruz, vice president and principal for landscape architecture and urban design at AECOM, the engineering firm that worked on the design. “We want people to feel very connected to its experience and how to navigate the park, he says. “Back in the day, when mechanisms for flood protection were put into place, they were erected without any consideration for how people use these spaces. We’re rethinking the way we think about open space and how we design around infrastructure.”

The redesigned park feels larger than it previously did, Mann says, with more outdoor “rooms” and space for concerts and other performances. It will also have a new energy-efficient pavilion with community space where nonprofits can have classes, and a rooftop terrace.

Gardens through the park are designed with native plants. The paving materials were chosen to help reduce the urban heat island effect. The solar-powered lighting in the park is DarkSky compliant to reduce the impact of light pollution on wildlife.

The plan for the transformation started more than a decade ago, after Hurricane Sandy devastated lower Manhattan. The storm surge reached 13 feet at Battery Park, at the southern tip of the island. Streets and subway tunnels were flooded. The power went out for days. Some offices closed for weeks. A hospital had to evacuate patients. Two residents drowned in a basement apartment in the East Village.

Wagner Park sits next to the Battery, but at a higher elevation. It avoided flooding during Sandy. But it’s in the 100-year flood plain.

The city recognized that major storms are becoming more likely because of climate change—both storm surges and heavy rain. And it knew that the park needed to be better protected. The new design is based on flood levels that are possible in the 2050s as the sea level rises.

The floodwall will connect to other projects to the north and south. Collectively, the new infrastructure will help make it less likely that the surrounding neighborhoods flood. That’s especially important now, Mann says, as the federal government is pulling back from climate action.

“As we’re getting less serious as a country about managing our greenhouse gas emissions, then we need to get more serious about how we actually adapt to a change in climate, he says. “I think it’s going to put more and more pressure on places to think about how do we actually grapple with the reality that increasingly looks like. And with some optimism, meaning, can we actually design better places? I think that this project, and other projects getting delivered now, provides some optimism that climate change adaptation doesn’t need to be just taking your medicine. It can actually be better space.”