Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert Kennedy Jr. has said that few medical schools teach their future physicians about how food can be the most optimal option for fighting chronic disease before it begins. He has now indicated he may defund medical schools that do not teach nutrition.

Whether we agree with this approach, the problem is part of a much bigger issue that both sides of the political divide have focused on — the unsustainable downward spiral of health care in the U.S.

The U.S. spends far more on health care than any other country in the world. Yet the average American dies younger than people in 60 other nations, including many with far fewer resources than we enjoy.

The U.S. health care system is less effective and more expensive than many other developed countries. A major reason for this is attributable to the many billions of dollars spent on managing preventable chronic illnesses — a cost that is drowning our health care economy.

Health care that promotes resilience and prevents chronic diseases sounds like a common-sense idea. But it is revolutionary and should be a wake-up call to all our citizens.

Put simply, much of health care in the U.S. is focused on reacting to avoidable problems rather than avoiding them in the first place. Our hospitals and health care clinics are essentially disease response systems, and our health professionals are trained to be disease responders. Our health systems aren’t focused on helping people be resilient before they become ill.

This is why nutrition is part of medical education, but usually doesn’t include the potential of diet to improve our function and quality of life. It rarely addresses food as preventive medicine to boost resilience or emphasizes that healthy lifestyles can reduce most major risks for developing or dying from a chronic illness.

Still, each day, we all make personal decisions about how we live our lives, decisions that directly affect our health.

Health care professionals have an obligation to examine the latest science, conduct new research, look for consensus and then share what we learn with our patients and the public in ways that can be understood and put into practice in a person’s daily life.

We have a duty to help people make decisions that can improve and preserve their health. But preventing disease before it occurs is not what most health professionals are trained to do.

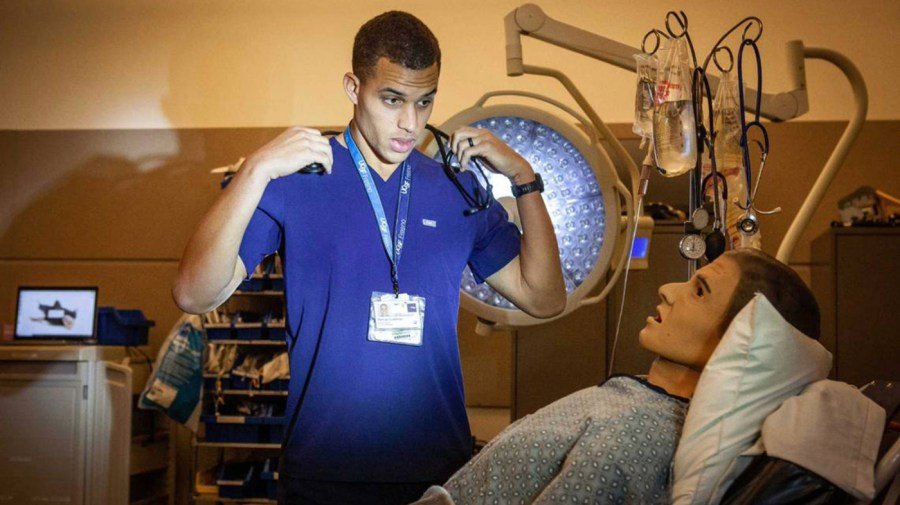

In an era where rampant misinformation drives what, when, and how most people eat, we are now presented with an opportunity to train the next generation of clinicians with practical, evidence-based approaches for patient education and engagement.

Change also means expanding the role of health care to provide reliable information that will help us all eat better, stay physically active and manage stress before it overwhelms us. It means designing communities where people can live longer and happier lives. It means addressing all the things that happen outside of traditional medical care, which influence our health at least as much as what happens inside a doctor’s office or hospital.

Many medical schools and health care systems already offer extensive programs to help their students and practicing clinicians stay well by being mindful of how they eat, move and maintain their mental health. Addressing “burn-out” and keeping our students well is important. But we must also teach them how to pass these lessons on to their future patients.

Once training changes, students can transform into their full role as health providers, rather than disease responders. Medical groups that employ doctors will then be able to insist on preventive whole-person health care as an essential part of the scope of practice for physicians and all health professionals.

Finally, insurance companies will see that reimbursing health care that promotes resilience is a far better investment than chasing preventable chronic diseases.

This change won’t come easily. Our society tends to encourage unhealthy habits. Our food industry relentlessly markets foods that are processed for economics over health. Our communities are built in ways that discourage human-powered travel. Video screens and video games are becoming our favorite ways to spend leisure time. And our jobs too often create more anguish than satisfaction.

Moving from ill-care to well-care will require a massive shift at many levels, but it can at least start with changing how we train our future doctors and health care clinicians. We currently require them to be excellent disease responders; we don’t require them to also become competent disease preventers.

Such profound change will have to start at the fundamental level of how we educate our future clinicians, at the beginning of training, when the seeds of cultural norms are planted.

But the critical first step can happen quickly and with minimal expense if the organizations that accredit medical schools, and all health professional schools, simply require that, in addition to responding to illness, graduates are also competent to address the neglected part of health care that improves well-being and resists disease. After all, that’s what the Hippocratic Oath requires.

Expanding medical education to include food as preventive medicine is a fundamental first step in the right direction. However, removing federal funding from schools should not be necessary. Instead, our leaders are well-positioned to partner with the national accreditors of health professional schools to make these changes through expeditious pathways that lead to far more sustained and profound change.

As a physician, I see U.S. health care facing a critical choice. We can sit back and wait for people to come to us, hoping for repairs after their bodies have broken down. Or health care can embrace the challenge before us: to continue to cure when we can, but also to prioritize health and well-being that promotes resilience.

Scott M. Fishman, MD, is a distinguished professor emeritus of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine and Anderson Endowed Chair in Wellness Education at the University of California, Davis School of Medicine.