When it comes to famous holes in the ground, northern Arizona has two: Grand Canyon and Barringer Meteorite Crater.

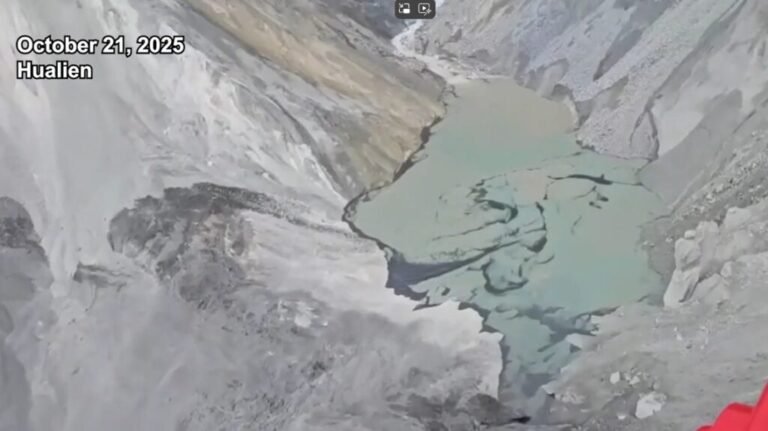

New research now suggests that these famous depressions might, in fact, be linked—the impact that created the crater roughly 56,000 years ago might also have unleashed landslides in a canyon that’s part of Grand Canyon National Park today. Those landslides in turn likely dammed the Colorado River and temporarily created an 80-kilometer-long lake, the team proposed. The results were published in Geology.

Driftwood Then and Now

“These are two iconic features of Arizona.”

Karl Karlstrom, a geologist recently retired from the University of New Mexico, grew up in Flagstaff, Ariz. Grand Canyon and Barringer Meteorite Crater both were therefore in his proverbial backyard. “These are two iconic features of Arizona,” said Karlstrom.

Karlstrom’s father—also a geologist—used to regularly explore the caves that dot the walls of Grand Canyon and surrounding canyons. In 1970, he collected two pieces of driftwood from a cavern known as Stanton’s Cave. The mouth of Stanton’s Cave is more than 40 meters above the Colorado River, so finding driftwood in its recesses was unexpected. Routine flooding couldn’t have lofted woody detritus that high, said Karlstrom. “It would have required a flood 10 times bigger than any known flood over the last 2,000 years.”

The best radiocarbon dating available in the 1970s suggested that the driftwood was at least 35,000 years old. A colleague of the elder Karlstrom suggested that the driftwood had floated into Stanton’s Cave when an ancient landslide temporarily dammed the Colorado, raising water levels. The researchers even identified the likely site of the landslide—a wall of limestone in Nankoweap Canyon.

But what had set off that landslide in the first place? That’s the question that Karl Karlstrom and his colleagues sought to answer. In 2023, the researchers collected two additional samples of driftwood from another cave 5 kilometers downriver from Stanton’s Cave.

A “Striking” Coincidence

Modern radiocarbon dating of both the archival and newly collected driftwood samples yielded ages of roughly 56,000 years, with uncertainties of a few thousand years, for all samples. The team also dated sand collected from the second cave; it too had ages that, within the errors, were consistent with the sand having been emplaced 56,000 years ago.

The potential significance of that timing didn’t set in until one of Karlstrom’s international collaborators took a road trip to nearby Barringer Meteorite Crater, also known as Meteor Crater. There, he learned that the crater is believed to have formed around 56,000 years ago.

That coincidence was striking, said Karlstrom, and it got the team thinking that perhaps these two famous landmarks of northern Arizona—Meteor Crater and Grand Canyon National Park—might be linked. The impact that created Meteor Crater has been estimated to have produced ground shaking equivalent to that of an M5.2–5.4 earthquake. At the 160-kilometer distance of Nankoweap Canyon, the purported site of the landsliding, that ground movement would have been attenuated to roughly M3.3–3.5.

It’s impossible to know for sure whether such movement could have dislodged the limestone boulders of Nankoweap Canyon, Karlstrom and his colleagues concede. That’s where future modeling work will come in, said Karlstrom. It’s important to remember that an asteroid impact likely produces a distinctly different shaking signature than an earthquake caused by slip on a fault, said Karlstrom. “Fault slip earthquakes release energy from several kilometers depths whereas impacts may produce larger surface waves.”

But there’s good evidence that a cliff in Nankoweap Canyon did, indeed, let go, said Chris Baisan, a dendrochronologist at the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona and a member of the research team. “There was an area where it looked like the canyon wall had collapsed across the river.”

An Ancient Lake

Using the heights above the Colorado where the driftwood and sand samples were collected, the team estimated that an ancient lake extended from Nankoweap Canyon nearly 80 kilometers upstream. At its deepest point, it would have measured roughly 90 meters. Such a feature likely persisted for several decades until the lake filled with sediment, allowing the river to overtop the dam and quickly erode it, the team concluded.

“They’re certainly close, if not contemporaneous.”

The synchronicity in ages between the Meteor Crater impact and the evidence of a paleolake in Nankoweap Canyon is impressive, said John Spray, a planetary scientist at the University of New Brunswick in Canada not involved in the research. “They’re certainly close, if not contemporaneous.” And while it’s difficult to prove causation, the team’s assertion that an impact set landslides in motion in the area around Grand Canyon is convincing, he added. “I think the likelihood of it being responsible is very high.”

Karlstrom and his collaborators are continuing to collect more samples from caves in Grand Canyon National Park. So far, they’ve found additional evidence of material that dates to roughly 56,000 years ago, as well as even older samples. It seems that there might have been multiple generations of lakes in the Grand Canyon area, said Karlstrom. “The story is getting more complicated.”

—Katherine Kornei (@KatherineKornei), Science Writer

Citation: Kornei, K. (2025), An asteroid impact may have led to flooding near the Grand Canyon, Eos, 106, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025EO250391. Published on 22 October 2025.

Text © 2025. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.