Few of Japan’s great photographers had a career as bold and multifaceted as Masahisa Fukase. Though largely defined by his black and white magnum opus Ravens (1986), a book of photographs in which the photographer casts himself as the grim black bird, Fukase managed to express facets of himself through many different proxies. He shot photos of his wife in a slaughterhouse and of himself in the tub. He returned frequently from Tokyo to his family photo studio in Hokkaido to shoot his family members in various poses and states of undress. His autobiographical approach contrasted with his more voyeuristic peers like Daido Moriyama and Nobuyoshi Araki; as the critic Nada Inada wrote in the introduction to his book (Yugi) Homo Ludens (1971), Fukase “prefers to stand in the light and expose himself to others.”

In Japan, Fukase is still a legend decades after a drunken fall rendered him comatose (he died in 2012). Nami, the bar in Shinjuku’s Golden Gai district where he suffered his accident, still displays one of his raven photos on the wall. And this year has seen increased interest in Fukase’s work thanks to a new biopic: Ravens (2024), starring Tadanobu Asano of Shogun (2024–26) and Ichi the Killer (2001) fame.

On paper, a movie about this mysterious and erratic artist sounds interesting, a chance to ramble through the shadowy thicket of Fukase’s life. But director Mark Gill, who helmed the Morrissey biopic England is Mine (2017), hinges the film on the utterly baffling decision to personify the photographer’s darkness in the form of an anthropomorphic raven.

I don’t mean an actual talking bird. Instead, a young Fukase, locked in his father’s photo studio as punishment for daring to apply to art school, begins seeing a top-hatted man-bird in a gothic raven costume. Wearing a beaky mask and all, and speaking in Spanish-accented English, this ridiculous character follows Fukase throughout the film, whispering sweet nothings that bid him to act on reckless and violent impulses.

It’s all too absurd. Fukase was a real person, not a Haruki Murakami short story protagonist. Instead of really engaging with why he was so drawn to morbid subject matter and how he could make such great art while living so chaotically and behaving so badly, this ridiculous magical-realist flourish completely cheapens his story and flattens the film’s engagement with his art. It implies that he was simply driven by a supernatural force of malevolence. Worse, it makes a joke out of the very real mental health struggles that drove the photographer to alcoholism and attempted suicide.

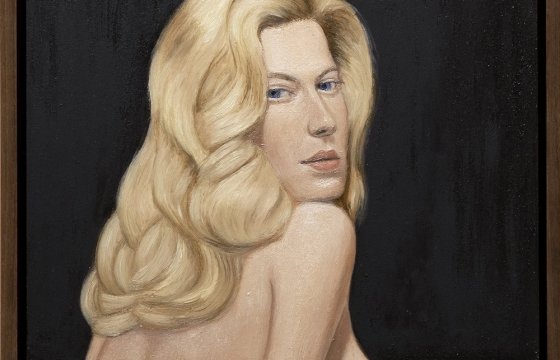

It’s not the only bad decision made by the director — the incredibly on-the-nose musical cue that ends the film is another — but the imposition of this devil-on-the-shoulder hallucination is especially confounding considering how well Gill manages to pathologize Fukase’s close relationships. The photographer’s marriage to Yoko Wanibe, a model who aspires to become one of the very few female performers in Noh theater, is marred by sexism and jealousy. He uses her as his muse but resents having to take commercial work to support her training. And when the photos he takes of her end up in a 1974 show at the Museum of Modern Art, his jealousy at being upstaged by his female subject further destabilizes the relationship.

That insecurity is shown to have roots in family. The film depicts Fukase as a man living forever in the shadow of his rigid and abusive father, the source of both his photographic vocation and his self-doubting nature, to whom he’s always trying to prove the validity of his artistic pretensions. We see their relationship shift over the years from spiteful distance — Fukase scandalizes his parents when he marries Yoko without informing them — to, eventually, a begrudging mutual respect. When his father dies, he even takes photos of his cremated remains. Not all of us can simply cut our toxic family members out of our lives, not even artists. It goes to show that Fukase was such a fascinating, complicated person and artist that Ravens can only give us a taste of his world.

Ravens (2024) is screening as part of the New York Asian Film Festival at Walter Reade Theater (165 West 65th Street, Upper West Side, Manhattan) on July 20.