Ford wants a do-over. The automaker invested billions of dollars bringing out its first long-range EVs, the Mustang Mach-E and F-150 Lightning only to wind up taking a $19.5 billion hit last year scrapping that program.

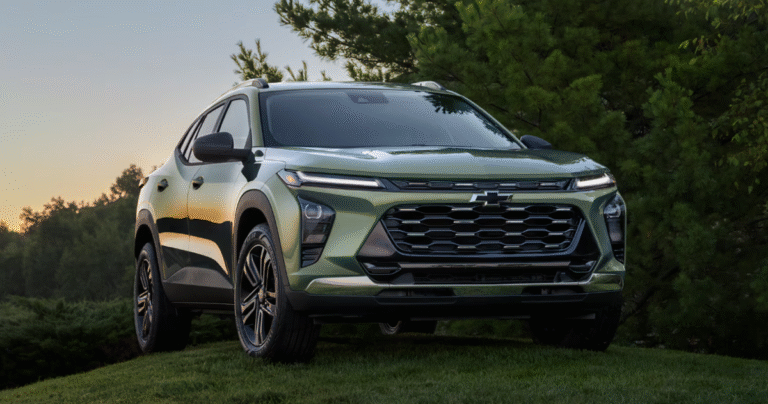

While it’s pulled Lightning from production and abandoned work on a pricey 3-row SUV, Ford is getting ready to take another shot at the battery-electric market with the “Universal EV” program set to debut next year. The goal is to deliver the sort of low-cost, long-range, fun-to-drive products that can give it a leg up on competitors like General Motors, Volkswagen, Toyota – and even Tesla.

To pull it off, Ford quietly launched a skunkworks program based out in Long Beach, California, well away from its main corporate product development operations. It gave its new team a mandate to rethink just about everything that goes into automotive design, engineering and manufacturing. While we won’t get to see the first product – a Maverick-sized all-electric pickup – until later this year, Autoblog did get a chance to talk to some of the Universal EV team leaders about what they’ve come up with.

Starting From Scratch

When Ford rolled out the Lightning four years ago it switched to an all-electric drivetrain and got some neat features, like its massive frunk, but it didn’t stray all that far from the formula that had made traditional versions of the pickup best-selling vehicle in America for more than three decades. Despite tooling up to build as many as 150,000 of the EV trucks annually, sales were little more than an asterisk on the F-Series chart.

Related: Ford Updates Plans: 5 New Affordable Vehicles by 2030

The automaker isn’t playing it safe this time around. The Universal EV team is intent on touching every element of EV design, engineering and manufacturing. And, in the process, they’ve set some aggressive targets for themselves. Alan Clarke, the project leader sums it up this way. His goal is to “Build electric vehicles that are not just fun to drive but which can compete on price with the best, including gas vehicles.” That starts with a Maverick-sized all-electric pickup set to begin rolling out in 2027 at a base price of under $30,000. In the years to follow, he said during a background briefing, we can expect a variety of additional body styles, from 2- and 3-row SUVs to commercial vans, perhaps even an all-electric sedan.

Attacking the EV’s Biggest Problem

If you’re starting from scratch, the best place to begin is the battery pack which typically accounts for about 40% of the cost of an EV, noted Clarke. Where Ford initially turned to the most high-density batteries available for Lightning and Mach-E, the Universal EV family will with lithium-iron-phosphate. While it can store quite as many electrons in a given mass, the chemistry has some key advantages: it’s cheaper, far less likely to suffer “thermal runaways” – read: fires – and doesn’t rely on costly metals like nickel and cobalt largely sourced from China.

Related: 5 Game-Changing Batteries That Will Change Your Life

To make up for that lower energy density, Ford approached things like “a puzzle,” explained Clarke. “We’re trying to fit the most cells possible inside the pack.” That, in itself, can save a substantial amount of weight, helping offset any advantage of lithium-ion chemistry. In turn, the new pack becomes a part of the Universal EV platform’s structure, further reducing weight while also enhancing the vehicle’s rigidity.

Casting a Wide Net

To further enhance the structure, the team lifted a page from the Tesla playbook. The underlying, skateboard-style platform is Ford’s first use of aluminum unicasting technology – the Texas-based rival calls them “megacastings.” Compared to the similar-sized Ford Maverick, the all-electric pickup will replace 146 separate steel parts in the front and rear chassis structure with just two huge aluminum castings, noted Vlad Bogachuk, who oversees vehicle structure efforts. That has a number of advantages, starting with mass – which is “one of the biggest efficiency robbers” in any vehicle. The unicastings are 27% lighter than the collective parts they replace, while eliminating 27% of the fasteners that otherwise would be needed.

Related: Tesla Quietly Cut 400 Pounds From the New Model X — Here’s How

Large-scale aluminum castings are beginning to be used around the industry – but they do have a potential disadvantage when repairs are needed after a crash. To make things easier, noted Clarke, the front and rear structure will literally feature dotted lines showing mechanics where to make cuts, when needed, to minimize work at the body shop. And that should mean substantially lower repair costs.

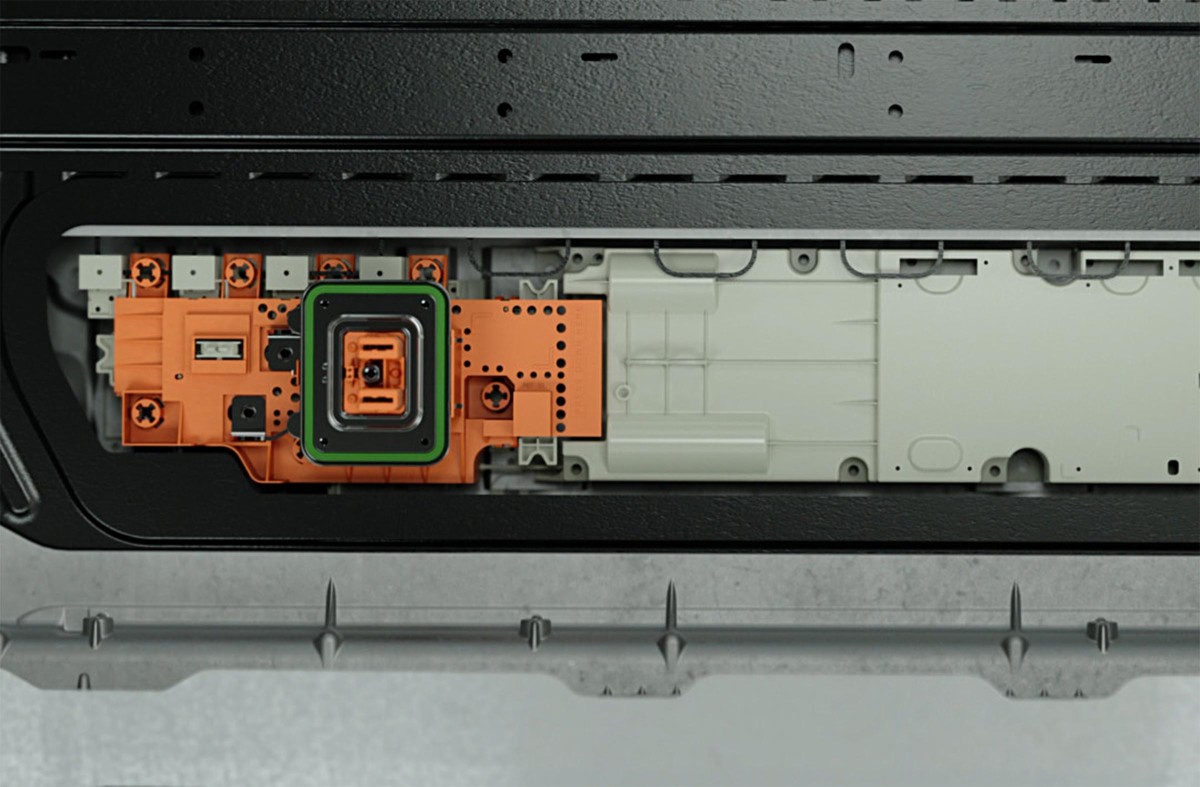

E-Box

Battery-electric vehicles are complex, to put it bluntly. One of the key goals of the Universal project was to simplify things, wherever possible. Part of the approach, said Clarke, was finding ways to make one part do the job of two in traditional EV designs. One example: the light, flexible, multi-layered circuit board used to control the powertrain replaces the scores of parts used on Mach-E and Lightning. And the high-speed DC and lower-voltage AC chargers now share many components. The process was further enhanced by migrating from 12 to 48-volts for many ancillary electrical and electronic components.

Again, learning from Tesla, Ford’s engineers also migrated to a “zonal” electrical architecture. Modern vehicles use seemingly countless numbers of electric and electronic components: from seat heaters to the sensors used for advanced driver assistance systems. Normally, each has its own microprocessor scattered around the vehicle. Instead, Universal EVs will consolidate that down to five centralized processing systems. And it will use an “E-box” to oversee everything, a system constantly monitoring how the vehicle operates and adjusting things on the fly, as necessary.

One of the benefits? A less complex wiring harness. Compared to some of Ford’s earlier EVs, the new electrical architecture will require about 4,000 feet less copper wire, shaving another 22 pounds of range-stealing mass.

Cheating the Wind

When it comes to an EV, weight is clearly the enemy. But so is the wind. Optimizing aerodynamic design is essential, said Saleem Merkt, the team’s aerodynamic lead. Even the subtlest tweaks can have big consequences. By lowering the roofline of the electric pickup, for example, designers were able to improve its aerodynamic “count,” enough to save about $1.30 in battery costs. And by redirecting air coming off the back of the rood they were able to eliminate the normally buffeting around the truck’s bed. “To the air, it’s no longer a pickup.” The sideview mirrors were downsized and a sealed underbody pan helped further reduce turbulence. One side benefit: less drag around the half-shafts should improve their durability, Merkt noted.

The payoff has been substantial, he added. “If the same battery were married to the aerodynamics of the most aerodynamically efficient midsize gas truck in the U.S. we believe our new truck would have 50 miles, or 15% more range.” And, at highway speeds, where drag increases exponentially, the data shows a 30% improvement. This allowed Ford to downsize the battery a bit more, even while retaining a target range of at least 300 miles, saving about $100 in parts costs in the process.

Redesigning the Assembly Line

It’s been more than a century since the automaker’s founder, Henry Ford, switched on the first movable assembly line. There’ve been a number of updates since then, notably the high-efficiency Toyota Production System that other carmakers – including Ford – have struggled to match. Now, however, the Detroit automaker plans to play leapfrog. Fewer, simpler parts should translate into a more efficient assembly process, team members suggested. The unicasting system will require fewer robots in the body shop, said Bogachuk.

That would be significant in a traditional plant. But Ford is set to make even more dramatic changes after completing a $2 billion makeover of the Louisville (Kentucky) Assembly Plant where Universal EVs will be assembled. Instead of having a single, moving assembly line, each EV will be assembled sandwich-style. There will be three adjacent sub-assemblies – one for the front of the vehicle, one for the rear, a third for the battery pack – they will be married together near the end of the line. During the original announcement of the Universal EV project last year, Ford officials estimated they could roll out new vehicles 40% faster than on a traditional assembly line.

A Big Bet

That $2 billion investment in Louisville is just part of the investment. Ford is pumping another $3 billion into its Blue Oval Battery Plant in Marshall, Michigan. And there’ll be hefty investments in other parts and components plants. Considering what Ford wrote off last year, it can’t afford to blow things again. CEO Jim Farley has promised this time Ford will deliver. It won’t happen overnight. But he’s confident the automaker will be able to begin to lower its EV losses this year and, once the operation in Louisville is fully up to speed, turn a profit starting in 2029.

While the Universal EV project will launch with a compact pickup, we’ll start seeing more body styles start to roll out a year later, with insiders hinting a 2-row EV is likely next to follow.

As for hard details on the pickup? Ford will keep us waiting for range and performance numbers until closer to its formal debut. Expect to see at least two battery pack options, with a main 300+ mile pack and a lower cost alternative that could be closer to 200 miles. We may see both 2- and all-wheel-drive options as well.

Meanwhile, Clarke said some of the technologies developed for the Universal EVs could also wind up helping Ford deliver more efficient and affordable hybrids in the years to come.