Somewhere around the turn of the 20th century, archaeologists in Heerlen, Netherlands, came across an odd-looking smooth white stone. They knew the territory was once the Roman settlement of Coriovallum, but had never seen anything like it and had no idea what it was for.

For the better part of the next 100 years, it sat in a storage unit at the Thermenmuseum, a mystery taunting researchers. Then, six years ago, archaeologist Walter Crist spotted the stone while wandering the museum. Crist specializes in ancient board games and recognized it as one, though not one he had ever seen before. That sparked his curiosity. Now, with the help of artificial intelligence, he thinks he has figured it out—and even knows how to play.

The stone isn’t much to look at. It’s an eight-inch piece of white Jurassic limestone. Lines etched into it form an oblong, diamond-like shape within a rectangle. But in a paper published Wednesday in the journal Antiquity, Crist and his team discuss what happened when they programmed two AI agents from the AI-driven play system Ludii to try to solve it.

Playing Ludus Coriovalli

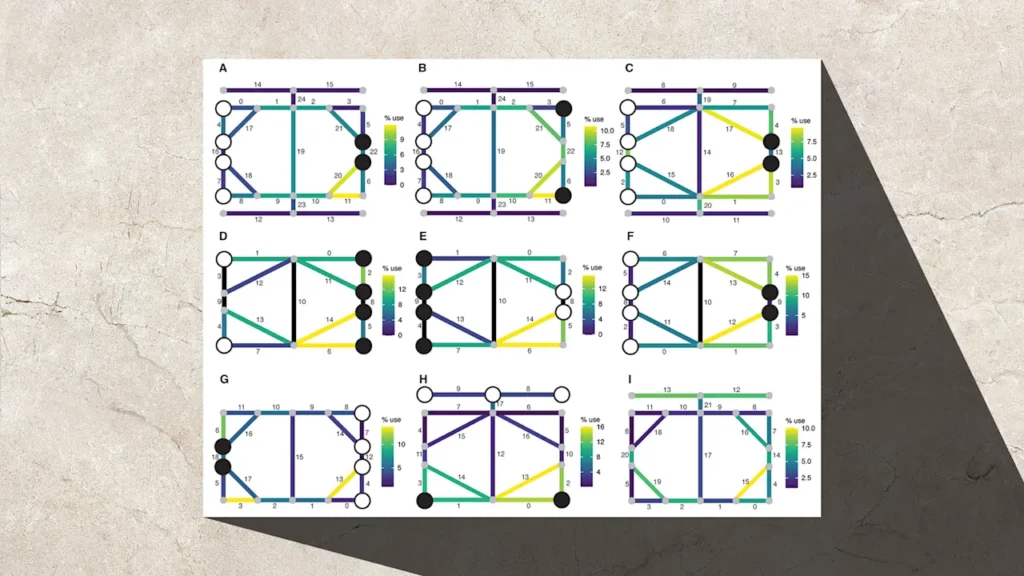

The researchers had the AI play the game against itself thousands of times, testing more than 100 different sets of rules drawn from other known European games, both modern and ancient. They compared the AI’s moves with patterns of wear on the board, tracking which gameplay styles most closely matched the grooves on the stone.

The board, it appeared, was used for a blocking game—a type of board game in which the goal is to prevent your opponent from moving. (Think of modern titles like Go or Blokus.) Blocking games were rare in ancient Europe and, before this, had only been dated to the Middle Ages. This discovery suggests they were played several centuries earlier.

In the end, the AI and the team identified nine sets of rules consistent with the board’s wear. Crist and his team named the game Ludus Coriovalli, “the game from Coriovallum.”

“By combining AI simulation with use-wear analysis to identify and model traces of game play, it is possible to not only identify potential game boards, but also to rebuild playable rulesets that may provide indications regarding the ways that people played games in the past,” the paper reads.

So what were the rules? Here’s what researchers determined:

- One player controls four “dogs.” The other controls two “hares.”

- The dogs start on the four leftmost points; the hares start on the inner two points on the rightmost side.

- Players alternate turns moving a piece to an adjacent empty spot on the board.

- The dogs attempt to block the hares, while the hares try to remain unblocked for as long as possible. If the hares are blocked, players swap roles and play again.

- The player who lasts the longest as the hares wins.

Got it? Good. Because this isn’t just a theoretical reconstruction. It’s a game you can actually play online now. Crist and his team uploaded a simulation of Ludus Coriovalli to Ludii, and it’s available to anyone who wants to give it a try.

So why study the games ancient civilizations played? Beyond simple curiosity, Crist notes, they offer a clearer picture of everyday life in the past—and a connection to history that isn’t just dry numbers or broken pot shards.

“The ability to identify play and games in archaeology strengthens the understanding of our ludic heritage, and makes ancient life more accessible to people in the present, as the act of playing a board game is fundamentally the same today as it was in past millennia,” he writes in the paper.