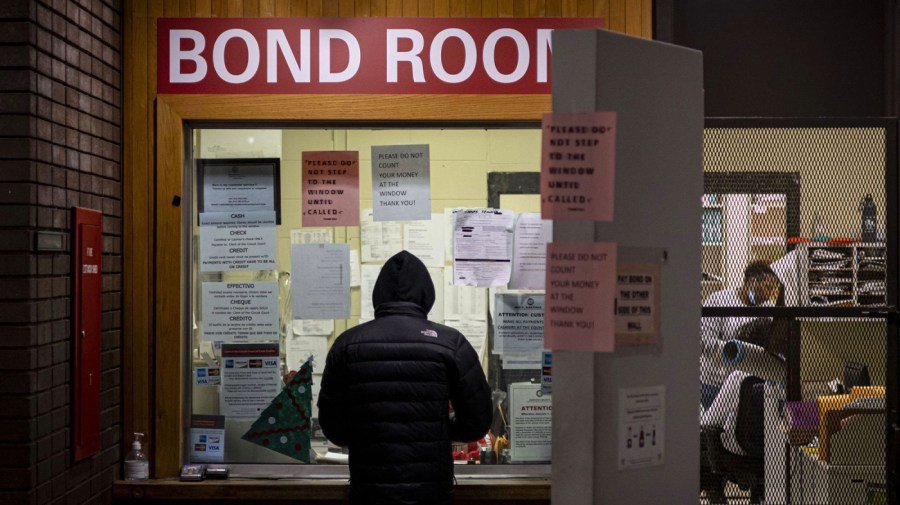

President Trump’s executive order wields a cutoff of federal funds as a threat to pressure jurisdictions like Washington, D.C., to stop releasing defendants without forcing them to post a payment, typically through a bail bondsman.

In D.C., 1 percent or fewer of defendants on pretrial release are rearrested for a violent offense. Yet the president is right about one thing: Even if it’s relatively rare, it’s galling when defendants freed prior to trial are rearrested for serious crimes.

The president’s action is largely symbolic, since the Constitution leaves bail policies in non-federal cases to state and local governments.

But his engagement has reignited debate over how to improve pretrial justice. Accomplishing this requires avoiding misconceptions about the purpose of bail and aligning policies with the best available evidence.

Our system insists that suspects are innocent until proven guilty. And forcing defendants to buy their freedom until trial does not prevent them from committing other offenses. Rather, it means that wealthy high-risk people can pay to go home, while those who pose little safety risk but happen to be poor are likely to languish in jail.

A key misconception is that paying bail disincentives criminal activity. It is important to understand that even defendants who stay clean and show up in court do not recover the non-refundable 10 percent of the bail amount that they typically give a bondsman.

A related misconception is that the purpose of bail is punishment. That would be unconstitutional, since at the stage of bail the defendant’s case has yet to be adjudicated. Dating back to colonial times, the lawful purpose of bail is to provide some guarantee of the defendant reappearing for trial.

Although the executive order bows to these misconceptions, policymakers can take several steps to curb new crimes committed by defendants released pretrial.

First, we must empower judges to deny bail in serious cases after due process.

Some 41 state constitutions contain a right to bail, and in some instances its scope has been overly broad. Consequently, states from New Jersey to New Mexico have adopted amendments carving out exceptions for the most serious cases.

Similarly, Texas voters are expected in November to approve a bipartisan constitutional amendment that makes commonsense changes, such as allowing denial of bail for defendants charged with ordinary murder, not just capital murder.

Notably, these amendments provide extensive due process protections, including the right to a hearing with counsel and an expeditious appeal.

Just as importantly, a judicial decision to deny bail altogether, unlike a court setting an unaffordable bail amount, has the same effect regardless of the defendant’s wealth.

Second, we must equip courts with better tools. People charged with the same crime often vary widely in risk level. Factors such as age and prior violent convictions, for example, are highly predictive of re-arrest, and they are part of risk assessment instruments that can help judges make more informed pretrial decisions.

Kentucky is a longtime leader on pretrial justice, having banned commercial bail in 1976 and in 2013 adopted a risk assessment tool that effectively predicts both pretrial appearance and arrest rates. Research indicates that such actuarial assessments can help ensure release decisions are based on objective factors, not extralegal ones such as wealth or race.

This is especially true when these instruments exclude minor drug possession arrests (driven largely by a person’s proximity to law enforcement), account for the recency of prior convictions and consider whether a failure to appear in court was promptly corrected.

Finally, we should strengthen pretrial supervision and services. In Virginia, just 5 percent of defendants supervised by pretrial services agencies are rearrested for a new offense.

Although requiring defendants to pay for their release does not reduce the risk that they will commit a serious crime, enforcing conditions attached to their release can make a difference. So can interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy and supportive services linked to the defendant’s individualized assessment.

In some cases, a pretrial services agency may connect a mentally ill defendant with needed treatment. In others, it may use electronic monitoring.

Pretrial defendants being monitored may be deterred from committing new crimes by the knowledge that their movements are tracked and even cross-referenced with crime reports.

In contrast, requiring all defendants to pay for their pre-trial freedom could lead to more costly jail beds consumed by low-risk defendants.

For example, before New Jersey’s comprehensive reforms under Gov. Chris Christie (R), which largely ended the use of cash bail and bolstered pretrial services and supervision, some 800 defendants remained jailed because they could not come up with 10 percent of their $500 bail.

Not only have taxpayers saved millions on unnecessary incarceration that often disconnects defendants from supports like family, employment and housing that reduce re-offense risk, but research also shows that reforms have not led to more gun violence.

Pretrial decisions often require balancing the values of individual freedom and public safety, but using a defendant’s wealth to tip the scales of justice fails to advance either.

Instead, policymakers can make their communities safer by giving judges sufficient discretion to deny bail in serious cases, enhancing the use of individualized risk assessments and ensuring that those who are released receive the right interventions to maximize their chance of success.

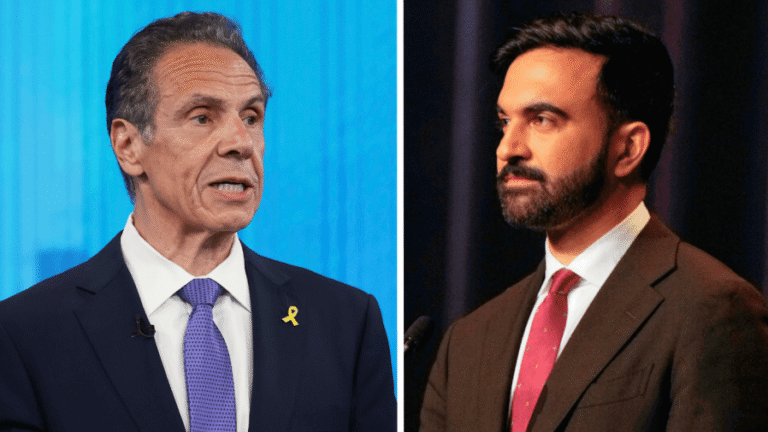

Marc A. Levin, Esq. and Khalil Cumberbatch co-lead the Centering Justice Initiative at the Council on Criminal Justice, where Levin is chief policy counsel and Cumberbatch is director of engagement and partnerships. They can be reached at mlevin@counciloncj.org and khalil@counciloncj.org.