That “hard cases make bad law” is a longstanding maxim among lawyers and judges. It may be time to add to it that celebrity cases often make bad law as well.

Think about O.J. Simpson, Kobe Bryant, or Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs. The media obsession. Massive pretrial publicity. The best legal talent money can buy. The list of things that make celebrity cases hard goes on and on.

Conventional wisdom has it that, in their encounters with the legal system, celebrities are treated better than ordinary people. “Just as there is ‘white privilege,’” according to one commentator, “celebrity defendants possess a supercharged version — one that trumps even race. At every step of the criminal justice process, the rich and famous have ways of avoiding liability which are unavailable to you or me.”

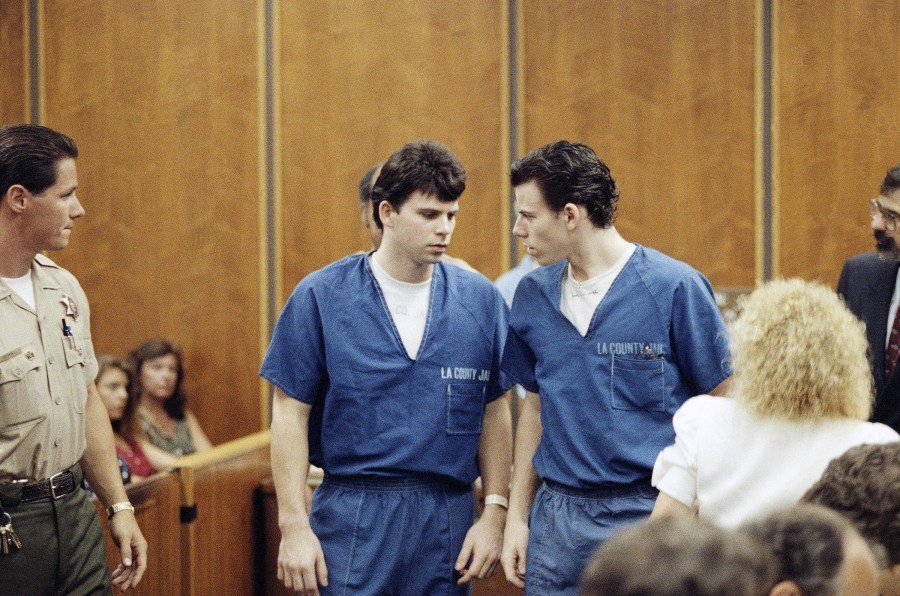

This “celebrity privilege” allegedly results from “the reluctance of an adoring public to admit the object of its affection is flawed.” But the picture is more complicated than is captured by conventional wisdom. Just ask Lyle and Erik Menendez, the brothers who were convicted and sentenced to life in prison without parole for the 1989 murder of their parents.

First, prosecutors may actually be more eager to go after celebrities when they are accused of crimes because the notoriety associated with their cases means that they have more bang-for-the-buck in terms of deterrent. Legal officials know they will be watched closely, and that their every decision will be scrutinized to see if it comports with notions of equal justice.

They may be stricter and more unforgiving as a result. And today, the media environment is much more voracious than it was when the Menendez brothers or O.J. Simpson were put on trial. That means more scrutiny.

Finally, there is celebrity gained before a criminal accusation and celebrity gained as a result of it. Last year, for example, Luigi Mangione attracted a legion of admirers in the wake of his cold-blooded killing of health insurance company executive Brian Thompson.

This brings us back to the Menendez brothers. Like Mangione, they became celebrities because of the crime they committed.

As The New York Times notes, “The case transfixed the country.” But their newfound celebrity did not spare them.

Three decades later, their celebrity got a new lease on life when Netflix released a movie about their case. That helped inspire a social media campaign to convince California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) to grant them clemency.

Last February, the governor directed the parole board to take the first step in the clemency process by investigating whether the brothers pose “‘an unreasonable risk to the public’ if released.”

In May, a judge followed the recommendation of Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascón and resentenced them to 50 years to life. Because of the amount of time they have already spent behind bars, they became eligible to apply for parole.

No doubt their celebrity played a large role in getting them that ray of hope. Even one of their lawyers acknowledged that “There are thousands of people like Lyle and Erik who don’t have the celebrity, don’t have the personality, and don’t have the good fortune of a supportive family, to lift their case up.”

However, last month, we again saw the limits of celebrity privilege.

On Aug. 21, Erik was denied parole. Explaining why, one of the parole commissioners said that when Erik killed his mother, he showed himself to be “devoid of human compassion.” He recounted Erik’s record of violations of prison rules and concluded he continues “to pose ‘an unreasonable risk to public safety.’”

One day later, Lyle was also denied parole. The commissioner who announced the decision said, “We find your remorse is genuine. … But despite all those outward positives, we see … you still struggle with anti-social personality traits like deception, minimization, and rule breaking that lie beneath that positive surface.”

Erik and Lyle got the same result that almost all prisoners get the first time they try for parole.

In the end, we can learn a lot about what has happened to the Menendez brothers by returning to the maxim about hard cases. Many people who invoke it ignore the full quotation in which Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes embedded it.

“Great cases,” Holmes said, “like hard cases, make bad law. For great cases are called great, not by reason of their real importance in shaping the law of the future, but because of some accident of immediate overwhelming interest which appeals to the feelings and distorts the judgment.”

Whatever one’s conclusion about whether judgment has been distorted in the Menendez brothers’ case, it is hard to dispute that, for more than three decades, their celebrity has sustained both the “overwhelming interest” and feelings to which Holmes referred. That fact is a reminder of the challenges celebrity cases pose for the law.

Holmes might have described those challenges as “a kind of hydraulic pressure which makes what previously was clear seem doubtful, and before which even well-settled principles of law will bend.” So far, neither that pressure nor their celebrity privilege has been able to carry the Menendez brothers to freedom, and that’s a good thing.

Austin Sarat is the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Jurisprudence and Political Science at Amherst College.