When I recently moved and needed a new mattress, I originally considered one made from memory foam. Then I realized that I didn’t know exactly what “memory foam” was even made of.

Some mattresses use fiberglass as a flame retardant. Some others include PFAS “forever chemicals,” plasticizers, or other chemicals linked to health issues, like formaldehyde. What’s inside a mattress, it turns out, takes a fair amount of research to determine. Recently, a handful of brands now make cleaner options. But building a better mattress can be complicated—and expensive.

The materials you may want to avoid

When fiberglass is used as a flame retardant, the material can spill out when someone removes their mattress cover or if the cover is torn. The tiny glass fibers can break and settle into dust. If you breathe it in, it can irritate your lungs. It’s often present even when a mattress says that it’s “nontoxic.”

In California, a new law will ban fiberglass in mattresses beginning in 2027. Still, if you buy a mattress now, there’s a chance that it will have the material in it. Fiberglass was supposed to be a replacement for older chemical flame retardants that were commonly used in other furniture and caused other health problems, from endocrine disruption to neurodevelopmental toxicity.

After regulations changed, manufacturers started phasing out most chemical flame retardants. But they still might show up in some mattresses, too. In a recent study in Canada that analyzed cheap memory foam mattresses made for children, researchers discovered flame retardants in almost every sample. In one case, a mattress contained a chemical that had been banned in Canada for more than a decade. The mattresses also contained other chemicals of concern, like plasticizers. Using the mattress can make the problem worse.

“What’s happening is that the body is heating up the mattress, and the chemical comes out more when you heat it up,” says Miriam Diamond, a professor at the University of Toronto and one of the authors of the study.

The study didn’t look for PFAS, the “forever chemicals” known for use in products like nonstick pans. But PFAS chemicals are also commonly used in fabric on mattresses. “I remember when I purchased my last mattress, they said, ‘We’re going to sell you this breathable, water-repellent, stain-resistant mattress protector, and you need to buy it in order to get the warranty,’” says Diamond. “And I thought, no, because those are the code words for PFAS: breathable, stain resistance.”

In some cases, brands might not even know what’s in the product they’re selling. The researchers were surprised to find flame retardants, and speculated that some might be showing up unintentionally because the equipment used to make foam was contaminated from other uses. Foam used in car upholstery, for example, still requires flame retardants, and could sometimes end up on mattress foam by mistake.

Mattresses also sometimes contain formaldehyde, a known carcinogen, in adhesives or bonding agents. Memory foam can emit other volatile organic compounds, including toluene, benzene, and acetaldehyde. If you’ve ever unrolled a bed-in-a-box style foam mattress, you’ve probably inhaled some of these chemicals.

The health impacts are greatest for children and pregnant women; it’s less clear how much long-term impact there might be for most adults. There’s little direct research. (There’s also no equivalent of the children’s mattress study, yet, for mattresses made for adults.)

But there’s also a long list of environmental reasons to avoid foam, beginning with the fact that foam is made from petrochemicals derived from crude oil. Workers in factories that make foam can have an increased risk of cancer. At the end of a foam mattress’s life, it typically isn’t recycled. At a landfill, it breaks down into microplastics that can contaminate soil and water.

A better mattress

With all of this in mind, I looked for alternatives. Some are much pricier than others. (If you have tens of thousands of dollars to drop on a mattress, you can buy a handmade Swedish option made from horsehair, cotton, wool, and traditional springs for $34,000.) But there are several other brands now making more sustainable options, including Avocado Green, Savvy Rest, and Naturepedic.

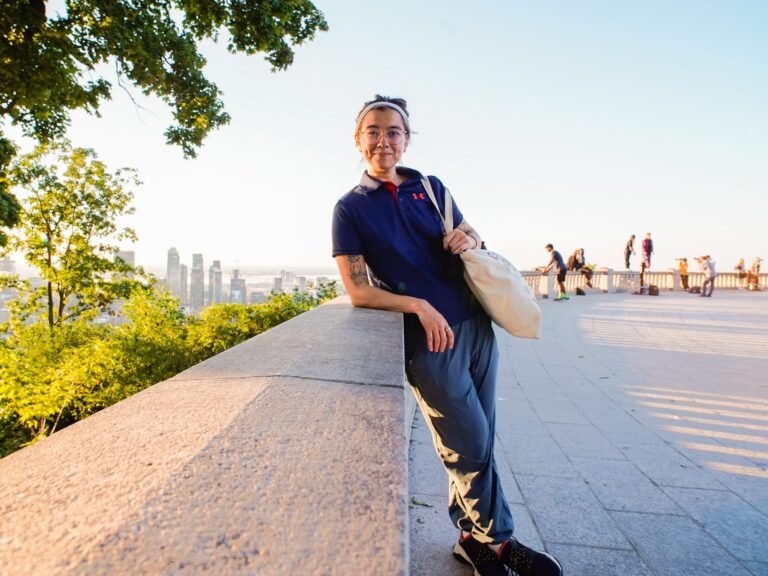

I decided to try a wool-and-latex mattress from Birch (currently $1,968), a brand that spun off from Helix, a popular decade-old mattress brand, because it had particularly good reviews for comfort. Birch sent me a sample to test.

The mattress has a layer of individually wrapped coils, two different layers of latex, a layer of wool (wool is naturally fire-resistant), and a cotton cover. The design took time to develop.

“Most beds in the industry are made from polyurethane foam that have a variety of different thicknesses and densities and firmness levels where you can mix and match certain things and to kind of get to a really great bed,” says Jerry Lin, one of Helix’s cofounders. “Those options aren’t as available in the natural and organic world. So honestly, it took a very long time for us to find the right mix of latex and organic wool and cotton to layer up a mattress that would be appropriate for the customer and the brand that we were serving.”

The wool, for example, comes from a supplier with machinery that made the wool “a little more bouncy,” he says, with more airflow than wool would typically have. The company similarly had to find the right suppliers for each component.

The latex is certified by GOLS, the Global Organic Latex Standard, as being made from organic, raw material and meeting standards for worker health and safety. It’s also certified by Greenguard Gold, a label that screens for more than 15,000 volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that can pollute indoor air.

When I unrolled the mattress from the box, there was no chemical smell—just a faintly sweet scent that seemed to come from the wool before it faded. Over the months that I’ve been testing it, it’s held up well; the mattress also has a 25-year warranty. It’s also very comfortable when I’m lying on my back. But as a side sleeper, it isn’t exactly the right fit for me. (That’s not to say it might not work for other side sleepers, but it’s a little more firm than I’d like, and I’ve been waking up with a sore shoulder.)

That’s the final environmental challenge: the brand is primarily online, though it’s growing its partnerships with physical stores. Like many consumers, I couldn’t try it out in person first. When I find a new mattress, I’ll likely have to ship another very heavy package across the country. And when I donate this one, I’ll have to hope that it doesn’t eventually end up in a landfill.