Following the Trump administration’s May announcement that all international students at Harvard University — fully 27% of the student body — must either transfer or face deportation, Attorney General Pam Bondi delivered an address justifying the government’s actions. There were eerie historical echoes to her statement blaming so-called anti-American radicalism at the nation’s colleges and universities; Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini made a comparable remark about Iran’s institutions of higher education in 1980. Similarly, it would be easy to imagine Iranian Minister of the Interior Mohammad-Reza Mahdavi Kani’s 1980 declaration that there should be a ban on “activities of all political groups in universities” being uttered today by Stephen Miller, White House deputy chief of staff for policy. Khomeini, in a 1981 radio address following his order to purge Iranian universities of “heretics,” thundered that “It is incumbent on both teachers and students … to do their best to identify corrupt elements and to cleanse schools of the dirt of these people.” And though it’s better composed than most Trump Truth Social posts, it wouldn’t be a stretch to imagine that appearing on the president’s social media page.

The similarities between the sentiments of extremists in Iran’s government 45 years ago and the United States today are obvious, so much so that the chilling statement by Kevin Roberts, president of the right-wing Heritage Foundation — that “we are in the process of a second American Revolution, which will remain bloodless if the left allows it to be” — is perfectly in the spirit of Khomeini.

Whether Otto von Bismarck’s Prussian Kulturkampf from 1871 to 1878 or Chairman Mao Zedong’s Chinese Cultural Revolution of 1966 to 1976, governments of both the right and left have occasionally implemented sweeping, oppressive, and frequently violent state-mandated social rebellions. Rather than simply altering political arrangements, a cultural revolution sees a nation go to war with itself. Under such a state, the government targets universities and media, museums and memorials. Marked by the negation and destruction of a nation’s institutions, such a process is by definition nihilistic. It is by nature anti-tradition, even if pursued by those on the right, whose conservatism has traded conservation for fervent authoritarianism. Finally, despite being controlled by a central power, cultural revolutions are inevitably chaotic. Though Trump and Mao are on opposite sides of the political spectrum, and few would confuse the United States president with the supreme leader of Iran, there are certainly leadership similarities. In The Cultural Revolution: A People’s History, 1962–1976 (2016), Frank Dikötter described Mao as “erratic, whimsical and fitful, thriving in willed chaos,” a leader who governed by instinct and improvization and who relished a “game in which he could constantly rewrite the rules … [where] people scrambled to prove their loyalty.” Sound familiar?

But Dikötter also writes that Mao was “cold and calculating,” as indeed the mavens of the Trump administration are, whether Bondi, Miller, or Roberts (or any number of others). Such disarray serves a purpose: A radical restructuring of all elements of America’s cultural life from higher education to the media. As legal battles are fought over words, so are cultural revolutions fought over aesthetics and imagery, over art. This is a noted departure from Trump’s first administration, wherein American cultural institutions, at least, functioned largely unhampered. The second Trump administration has an even more apocalyptic orientation. The 900-page Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 labels those who disagree with its sweeping proposals to expand draconian laws policing individual liberties at the expense of welfare, including assaults on women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights, labor rights, and free speech as “anti-American.” Its primary author, Russell Vought, the current and inordinately powerful director of the Office of Management and Budget, has bragged about how he wants those who fall under that label to feel “trauma.” The difference between this cultural revolution and those in Germany, China, or Iran, is not of kind, but of degree, and only so far.

The full litany of attacks on cultural institutions in particular should dissuade anyone from thinking that recent events are just more Trumpian randomness, as opposed to a concentrated, coordinated, and intentional multi-pronged effort. Take, for example, Trump’s elimination of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts’ nonpartisan board and his instating himself as chairman, as well as his ongoing assaults on higher education, from the withholding of promised funding for arts institutions to the recent attacks on Harvard. In May, Trump signed an executive order canceling federal funding for both the Public Broadcasting System and National Public Radio, referring to the organizations that, among other functions, fund the documentaries of Ken Burns, Ira Glass’s This American Life, Terry Gross’s All Things Considered, and Sesame Street as being “RADICAL LEFT ‘MONSTERS’ THAT SO BADLY HURT OUR COUNTRY!”

That same month, Trump fired the respected Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden — a patently unconstitutional move, since the institution is under the purview of the legislative branch, and one that has been challenged in court and bravely resisted by employees. White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt claimed that Hayden, director of a non-lending research library that collects all published material in the United States, was fired because she had put “inappropriate books in the library for children.” The latest proposed budget released this month requests the elimination of both the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts. Most recently, he attempted to fire the director of the National Portrait Gallery, citing her support for DEI initiatives.

Already allocated funds for both have been diverted to Trump’s “Garden of Heroes” memorial, a site that Gal Beckerman of The Atlantic perceptively compares to the monuments of Benito Mussolini, while applicants to the NEA have discovered that the organization will now prioritize projects that “celebrate and honor the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.” The little-known but crucial Institute of Museum and Library Services was forced to cancel millions of dollars in grants to organizations throughout the country, while the administration pressured the world-class National Gallery of Art to close down their offices committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion. Meanwhile, a March executive order with the Orwellian title of “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History” attacked the Smithsonian, eliminating positions and exhibitions with the intent to “remind Americans of our extraordinary heritage.”

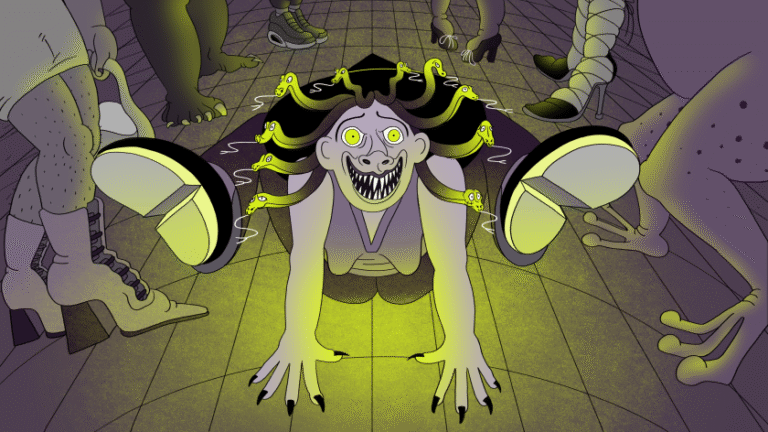

Predictably, Trump has replaced or is attempting to replace much of the leadership at surviving institutions and offices with lickspittle lackeys, middling non-experts who will devote what programs remain to pablum and kitsch, something obvious in the appointment of Siggy Flicker, a star of the Real Housewives of New Jersey, to the board of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Even if grifting were this administration’s only transgression, that would be bad enough. But the results of this cultural revolution will be entirely darker. A variety of different factions are involved in the Trumpian moment, from the Christian Nationalists of the so-called New Apostolic Reformation to the Dark Enlightenment movement in Silicon Valley, but a certain operative aesthetic seems to have emerged out of this mélange. Amanda Marcotte, in an astute March essay in Salon, examines the visual idiom of MAGA from the hyper-attenuated plastic surgery that she calls “Mar-a-Lago face” to the Tesla cybertruck, hideous right-wing AI memes to Elon Musk’s sartorial choices. “In theory, we all prefer beauty over ugliness,” she writes. “[That] last proposition … has been seriously challenged in the era of Donald Trump.” Examining the uncanny valley effect of the bizarrely similar facelifts of Matt Gaetz and Kristi Noem, to the odd AI memes that feature Trump and Musk as rugged cowboys, Marcotte describes how “Fascism, especially the 21st-century version practiced by the MAGA movement, is at war with reality. The hyperreality of the MAGA aesthetic is about power.”

I’d argue that AI art provides the perfect fascist aesthetics for MAGA, precisely because it’s so inhuman. That it slickly corresponds to the ideological commitments of the Silicon Valley supporters of Trump is an added bonus. Previous propaganda was still the creation of actual human beings. Even the most hinged of contemporary right-wing propaganda, such as the paintings of Jon McNaughton, who imagines Trump in a variety of heroic poses, whether surrounded by historical figures praying over him in the Oval Office or riding on a motorcycle with Melania holding on behind him, was still produced by an actual human being. Ultimately, McNaughton reads as more schmaltzy than truly ominous, whereas work made by artificial intelligence is truly of this current techno-fascist moment, not necessarily just because of what it depicts, but also because of how it was created. Images such as Trump riding upon a lion or triumphantly surveying the Canadian wilderness from the top of a mountain are fascist as a matter of course, but what’s most disturbing is that MAGA has achieved a kind of humanities-without-the-human, a true death of the artist themselves.

“The old world is dying,” wrote the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci in Prison Notebooks (1929), considering the implications of Mussolini. “Now is the time of monsters.” Certainly, ample digital monsters are on display in the video simulacra defined by this new MAGA aesthetic. Witness the perverse video that Trump shared which reimagines Gaza into a resort and where the residents supplicate before a golden statue of the president or the many slick productions of the mysterious Dor Brothers, whose algorithms create short films of a vaguely Goodfellas-adjacent Trump counting money, brandishing weapons, and surrounded by models, all of it animated with a propulsive hip-hop score. Such imagery, which is replete on platforms like TikTok and Instagram Reels, is conceived not by a mind but a computer, and is thus the perfect encapsulation of an era that’s now beyond aesthetics — and apparently, beyond politics. A form of fascism where the leader is less important than the image — indeed, where there is scarcely any relationship between the two. Focusing on the ample deficiencies of Trump’s character has always been a liberal’s category mistake, for the president scarcely matters as much as what he represents. One could imagine a dystopia governed by a hologram of Trump that wouldn’t differ much from the present. Which is to say that actual art, which is made by real people in circumstances divorced from this burgeoning monoculture, is now all the more subversive and all the more crucial. A return to community art, of face-to-face interaction, of work that isn’t reliant on the official channels of power. For there to be genuine resistance, it becomes all the more important that it’s local, and all the more crucially, that it’s human, with all the connotations of that word.