MIAMI — The first time Bex McCharen tried to photograph their extended biological family in the mountains of Virginia, something felt off. The camera created a distance rather than a connection; the intimacy wasn’t there. But in Miami, waist-deep in the Atlantic Ocean with their queer and trans friends, the opposite happens: Images arrive with ease. Bodies drift toward the lens without self-consciousness. Water softens everything.

“The ocean is like church for us,” McCharen said. “It’s where we go to feel accepted, held, and whole.”

The photos that emerge from these gatherings, depicting friends floating and laughing, form the raw material for Queer Atlantics, their newest body of work. On February 20, McCharen will host an evening at Green Space Miami as part of Women Photographers International Archive’s monthly Image Readings series, a community gathering where image-makers share and discuss works in progress.

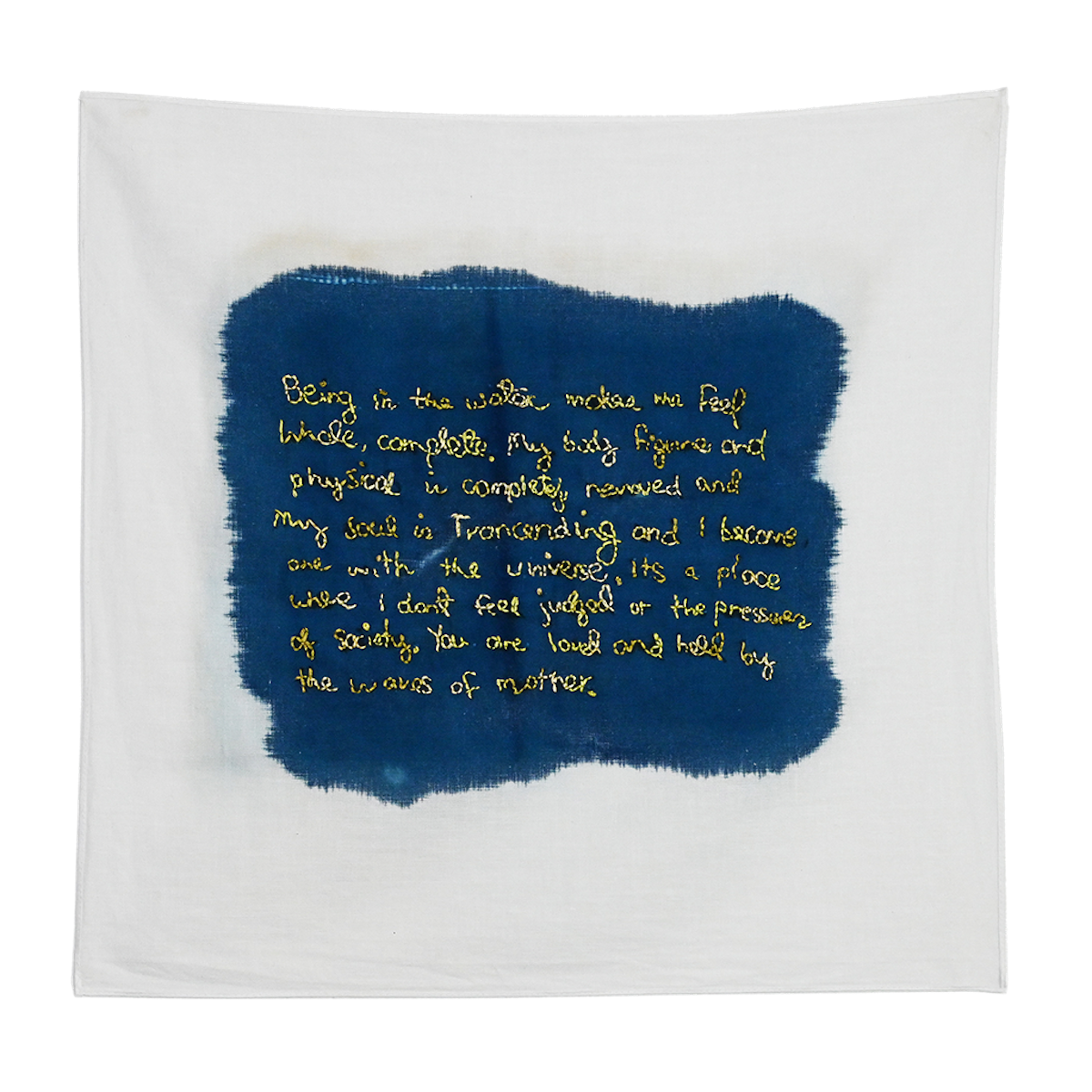

The event offers a rare chance to encounter the thinking behind McCharen’s newest body of work, a series of ocean-soaked photographs and quilts that transform Miami’s waters into a site of refuge, memory, and belonging.

Best known as the founder of Chromat, the body-inclusive fashion label now on hiatus, McCharen has spent the past several years shifting toward textile, cyanotype, and photography. In December, they debuted these works publicly in a solo presentation at Untitled Art Fair in partnership with Oolite Arts and Dot Fiftyone Gallery. The move into quilting marked a significant evolution, the language of swimwear and performance reconstituted into artworks that treat water as refuge in a moment when the state tries to legislate trans presence out of public life. From restrictions on gender-affirming care to attacks on drag and Pride, Florida’s recent legislative blitz has sought to render trans and queer people precarious, invisible, or gone.

McCharen has lived in Miami for nearly a decade, after first arriving for Swim Week in 2013. What started as seasonal work became permanent once they fell in love with local queer and activist communities. The water, they said, changed them.

“I went into the ocean as one person and came out another,” McCharen said.

It became the site of their gender transition and the place where their closest community gathers in the face of political hostility. Quilting, for McCharen, is the medium that can hold that transformation.

“Quilting is love and care and legacy,” McCharen explained.

It’s what swaddles infants; it’s what families pass down. They learned the craft from their mother, who learned from her mother, part of a long lineage of Mennonite quilters in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. Recently, relatives began mailing McCharen unfinished quilt tops and scraps from decades-old projects. Those fabrics, already soft from handling, form part of this new work.

But McCharen doesn’t see themselves as “modernizing” quilting.

“I’m doing what people have done for centuries,” the artist said.

When they’re unsure of a shape, they consult old quilting pattern books. One major piece in the Untitled presentation borrowed directly from a historic Mennonite design, but here, instead of calicoes and florals, the geometric structure holds cyanotypes of bodies underwater, digital prints of shoreline light, and the electric blues of Miami’s coastline. Quilting becomes a technology for preserving sensation: the drag of a wave across a back, the warmth of a friend pressed against your shoulder in the surf.

In their Oolite studio, a draped textile of blue photo-strips slumps off the wall like a towel just shaken out after a swim. It feels like a small sanctuary. Most of the images in the work come from casual days spent in the ocean, rivers, and springs with queer friends. Many were shot with a small GoPro.

“Photographing people is intimate,” McCharen said. “I have to feel comfortable with them, and they have to feel comfortable with me.”

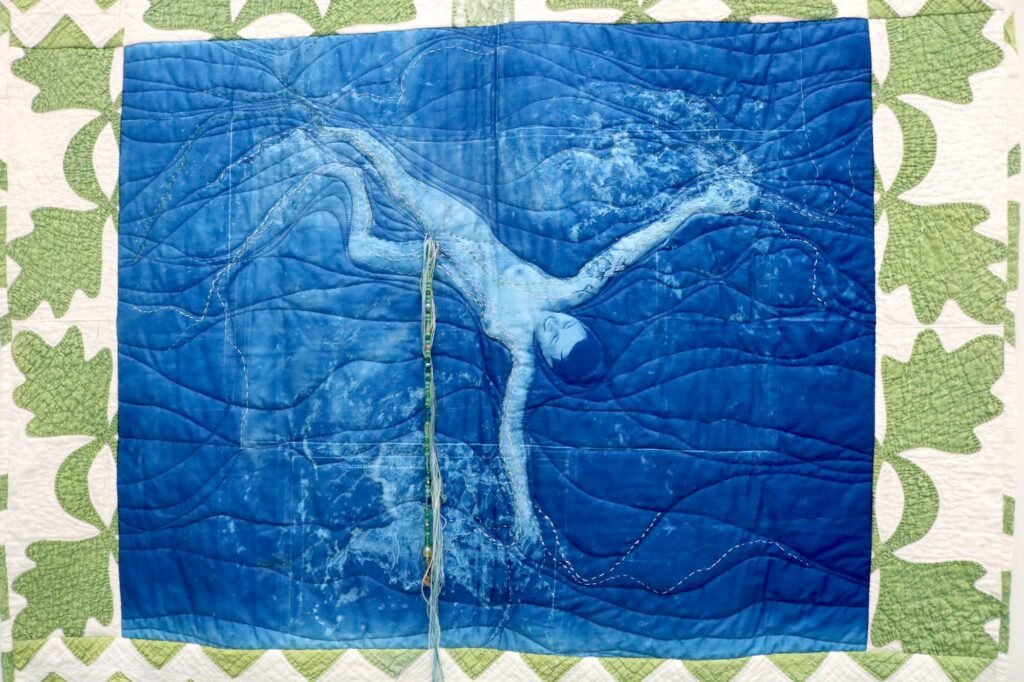

To translate these images into textile, McCharen creates negatives and prints cyanotypes on fabric, or uses Oolite Arts’ large-format printer to produce full-color panels. In “I am a river and my ancestral tributaries flow through me” (2025), a nude figure seems to dissolve into the water itself. Their limbs stretch across a field of deep blue. Hand-stitched lines radiate from the figure like veins emptying into an ocean. A long braid of beads and embroidery hangs down the quilt’s center, as if the river running through the body has breached the frame and continues its course into the world. It’s a quiet reminder, stitched into every seam, that we are all water.

In these works, pleasure and joy act as a form of survival. Florida’s legislative climate remains openly hostile to trans life, but McCharen refuses the logic of exile. Laws shift, but the ocean stays open when institutional doors close.

“Our relationship to the ocean is much deeper than whoever is in office,” McCharen said. “We’re not going to leave just because of whoever’s in power.”