Why China Pulled the Plug on Rock-Bottom Prices

China’s long-running price wars on electric vehicles have officially come to an end, and US buyers will probably never experience the kind of rock-bottom pricing it produced. China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) made the decision to bar all vehicle manufacturers from selling cars at less than manufacturing cost. This puts an end to the brutal homegrown competition that’s projected to have cost the automotive industry $68 billion.

This action will likely provide stability to the auto industry in China. However, this could also impact the way that global EV prices are decided. It comes at a time when other countries are deciding on ways to prevent super-cheap Chinese-made EVs from disrupting home markets.

How Chinese Manufacturers Set Prices So Low

Chinese automakers achieved their price advantage through multiple factors beyond government subsidies. They benefit from economies of scale in the world’s largest EV market, where electric vehicles now represent over 50 percent of new car sales. Manufacturers also leveraged extended payment cycles to suppliers and strategic vertical integration of battery production. Companies like BYD built complete supply chains, allowing rapid innovation, with Chinese firms developing new models in roughly half the timeframe compared to legacy automakers.

The price-war ban is aimed at manufacturers who were using artificially low prices to eliminate competition and gain control of the market. Several manufacturers were pushed to the brink of bankruptcy or disappeared altogether through these price wars, while many auto parts suppliers have been waiting as long as 300 days for payment.

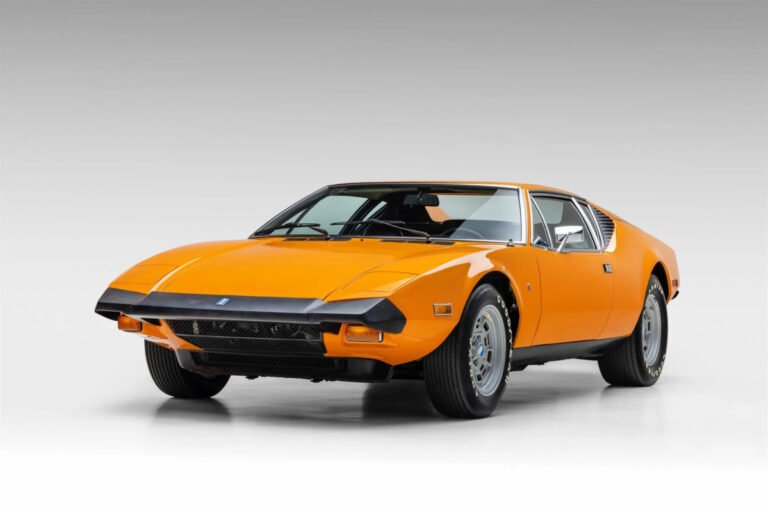

BYD

The Ripple Effect for American Buyers

Despite the current 100% tariffs on all Chinese electric cars in the United States, China’s pricing standards had created an international precedent that put pressure on American manufacturers to create more affordable EVs — ultimately a good thing for car buyers. Chinese EVs like the best-selling BYD Seagull small electric hatchback were being sold at $10,000 domestically, with a slightly tweaked version for European markets retailing at around $25,000 despite the relatively low tariff barriers in Europe.

If the cycle of ever-dropping Chinese EVs had continued (and they were available in the US), it could have saved US consumers between $10,000 to $20,000 in the purchase price of a new electric car. Now that tariffs on a limited number of Chinese EVs have been reduced to 6.1% in Canada, it could create potential pressure points in America. American automakers could now have competitors who have been sharpened through extreme domestic competition and restricted by tariff walls and domestic laws. Ultimately, US buyers will have to pay more for electric vehicles (even with manufacturer discounts), while the remainder of the world gains access to more affordable EVs.