What does it mean to love in a time of turmoil? It is an enduring question — and one I rarely hear asked of the medieval world. Looking to the Middle Ages for answers to the perennial puzzles of life can seem quaint, even artificial, a long reach across centuries marked by violence, hierarchy, and exclusion. And yet medieval culture offers a way of thinking about love that still speaks to the present. If love is most urgently tested in moments of strain and upheaval, then it is in those moments — where care is stressed or obscured — that its meaning comes most clearly into view.

In our own moment, we are living amid forms of exhaustion that make sustained attention difficult: humanitarian emergencies reduced to statistics, social care systems hollowed out by austerity, and digital economies that reward speed over responsibility. Care is not absent so much as continually deferred, obscured by scale, distance, and a growing insistence that vulnerability should be managed rather than answered.

Medieval European visual culture returns to moments of strain and trial again and again, often figuring them through blackness: through bodies marked by humility, penitence, and spiritual testing. Images of Black figures in the Western tradition are not rare, but love — in its fullest, most generous sense — is rarely what they seem to offer at first glance. In depictions of figures such as Saint Maurice, blackness often functions as a site of moral recognition, inviting viewers to identify with sanctity by confronting their own sin and insufficiency. Other familiar figures, such as Balthazar, likewise position blackness as meaningful primarily for what it signifies to the viewer — distance, universality, or the far reaches of Christendom — rather than as an interior condition. These images open space for identification and self-scrutiny, but they stop short of imagining blackness as generative: not merely a mirror of sin, but the ground from which love itself might take shape.

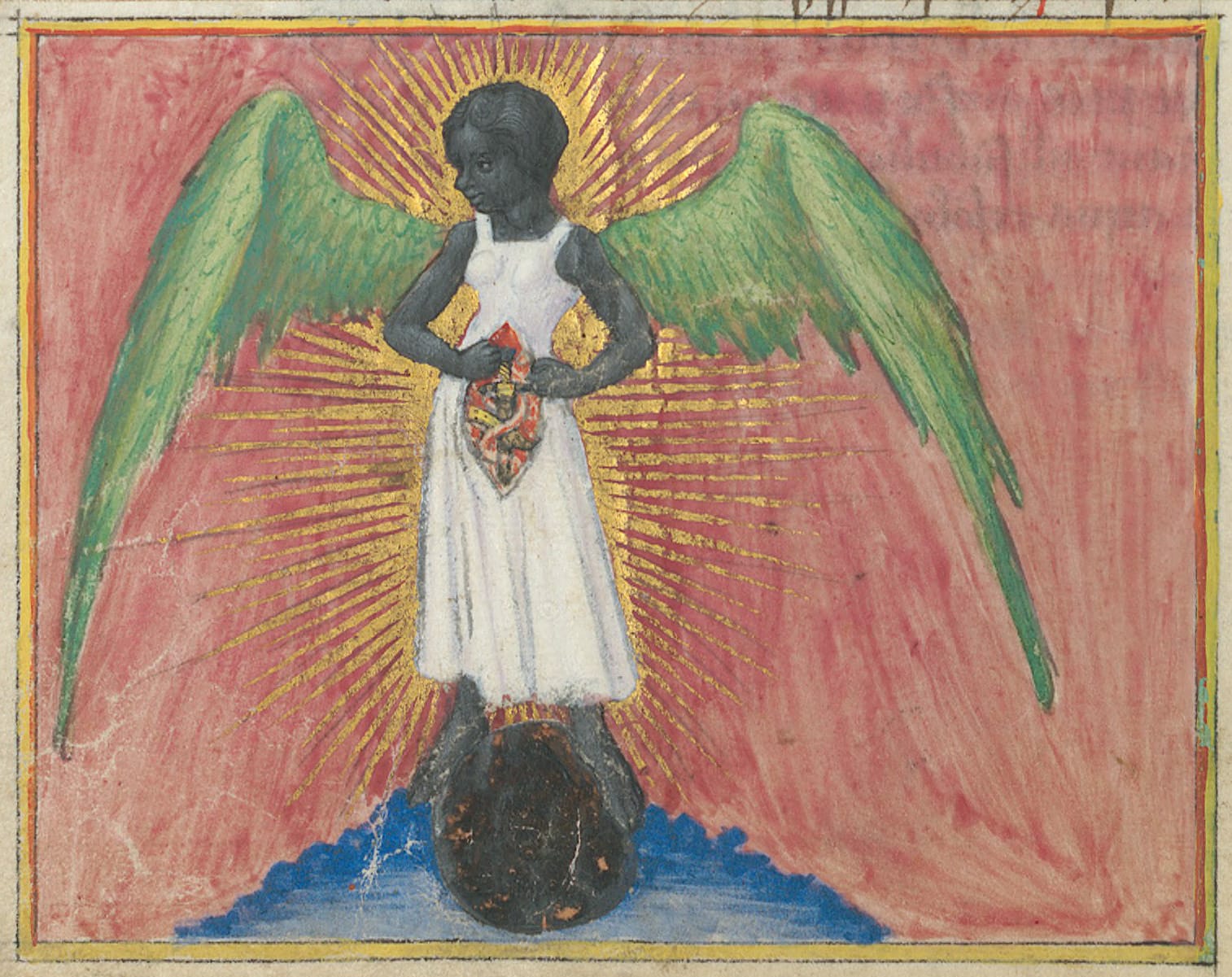

One image, in the 15th-century alchemical manuscript Aurora consurgens (Rising Dawn), complicates this way of seeing: a late medieval angel with black skin, green wings, and a body cut open to reveal a glowing red interior. In medieval theological and devotional writing, moral goodness was conventionally imagined through the language of light and whiteness. As the 6th-century theologian Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite writes in The Celestial Hierarchy, divine goodness overflows with light, illuminating all things according to their capacity to receive it — a formulation that shaped centuries of Christian thought about purity, hierarchy, and visibility. White garments, lightly colored hair, and white luminous flesh became visual shorthand for innocence, obedience, and sanctity.

As an angel, she is meant to embody these virtues. And yet her skin is black. Set against the warmth of the light that radiates from within, her blackness unsettles how goodness is meant to appear. What kind of love could take shape here?

The Aurora consurgens is a late medieval alchemical manuscript that combines dense, allegorical prose with striking images meant to guide the reader through a process of inner transformation. Attributed to a pseudo-Aquinas, the text reimagines alchemy not as the pursuit of material gold, but as a spiritual discipline concerned with humility, self-knowledge, and the gradual reformation of the soul. In the Aurora consurgens, nigredo, rubedo, and albedo are described as distinct stages within the alchemical process of spiritual transformation — but not as a simple ascent from darkness to light. Nigredo names a condition of contrition and unmaking; rubedo intensifies and exposes this state through heat, incision, and inner transformation; and albedo appears as a fragile, receptive condition rather than a final resolution.

Crucially, the text repeatedly warns that whiteness can be false or destructive if severed from what precedes it. Transformation here does not proceed by erasing blackness, but by carrying it forward, integrating it into a changed interior life capable of receiving love.

Angels, planets, and bodies recur throughout the manuscript as allegories for interior conditions, making this black angel not an isolated curiosity, but part of a larger visual system devoted to becoming, rather than achieving perfection.

To envision nigredo — the first stage of the transformation of the soul — as the skin and hair of the angel is to translate a spiritual condition of contrition, brokenness, and humility into the most material and inescapably human surface of the body. In the late Middle Ages, skin was understood as revelatory: it registered character, disclosed interior disposition, and marked one’s place in the world. Though affected by climate, labor, or emotion, it could not simply be shed. By locating nigredo on the skin rather than in atmosphere, shadow, or dress, the illuminator signals that this stage of the soul’s conversion is constitutive rather than peripheral, enduring rather than temporary — not a stain to be erased, but a condition one inhabits. Blackness here becomes visible on the body’s most exposed surface, rendering nigredo not as abstraction but as something shared, embodied, and recognizably human. It was this move — blackness understood as an enduring, human condition rather than a symbolic overlay — that first unsettled me and drew me to the image.

In the Middle Ages, blackness did not function primarily as a marker of identity. As scholars of the Middle Ages have shown, it operated on more than one register: both as a symbolic language rich with meanings tied to repentance and salvation, and as a framework through which racial thinking gradually emerged. As Geraldine Heng has shown in her study of Black holy figures, medieval imagery often used black skin as a surface of moral recognition: a visible sign through which viewers were invited to confront sin and spiritual vulnerability. Yet even within this hermeneutical tradition, blackness is often treated as static — the mark of sin awaiting purification, the darkness meant to be washed into white.

What distinguishes the Aurora consurgens is that blackness is not erased in the process of transformation. It is inscribed on the body itself, redefining transformation not as the removal of blackness but as the condition that makes the soul capable of receiving love.

In the Aurora, love is not imagined as purity already achieved, nor as transcendence beyond the human condition. It appears instead as a capacity, one that becomes possible only after the self has been unmade. The black angel embodies this logic. Her black skin does not signal a condition to be overcome, but the necessary ground through which love takes shape. Stripped of mastery and self-sufficiency, the soul becomes capable of receiving rather than possessing, of recognizing rather than judging. The image does not imagine love as reward or resolution, but as a capacity that follows unmaking — one that becomes possible only once the self has been broken open. The angel does not love despite blackness, but through it.

Taken seriously, this medieval image shows that the soul’s supposed “darkness” — its faltering, its confrontation with its own fragility — is not an obstacle to change but the condition that makes transformation possible. To say that we are all, in this sense, marked by blackness is not to erase racial specificity or historical difference. It is to name a shared movement through unmaking, the breakdown that precedes any genuine capacity for love. In a moment defined by turmoil and a staggering failure of empathy, the image invites us to understand love not as something reserved for the pure or the obedient, but as something that takes root precisely in vulnerability. Blackness here is not an ending, nor a condemnation. It is the space where love becomes possible in the first place.

Editor’s Note: This essay was based in part on a lecture delivered at the Love: A RaceB4Race Symposium organized by Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona, on January 24.