At the end of November of 2011, I saw my dad take his last breath. I came back to the United States after participating in all the death-related rituals that helped organize my pain in México. New York City was not a place to live my mourning, and right around December of the same year, I felt an intense longing to become small again. I needed to work with children. Another time, around 1990, I’d had a similar urge after finishing my own cancer treatment. I was seeking life.

I felt dizzy and disorganized working those first jobs with children. I went to art school and did not have an official training in childhood education, so I learned on the go. The children didn’t respond to logic, or at least not the logic that I was used to, like “up is up and not down,” like “a fork is for eating and not for drumming.” I ended my days feeling spellbound and inspired.

From all the ages that I worked with, my favorite were the two-year-olds. One child in my classroom had only a handful of words and a finger for pointing. With those minimal tools, she knew how to speak to the world. I didn’t notice shame or frustration, just presence.

I say that my accent makes me feel self-conscious. I know I should not feel that way — I know why I should not — but it still happens. Sometimes I identified with pre-verbal children, a term I learned in the Early Childhood Education Professional Development trainings. I kept the term with me to honor the bridge that I built with those children. When I was stumbling in my pronunciation of the wr sound in “writing” or “wrong,” the children in the classroom had a plethora of other non-verbal languages. When I stopped and studied the way children were using their mouths, I was mesmerized. Biting and a menu of different screams, yippings, and tootlings were common in the class. Bites were highly effective at communicating discomfort and the need for a kind of grounding, a feeling of being in the body. I saw children taste clay, lick plastic toys, and sample the classroom tables. I took that intimacy and revelation with me and brought it into my art, performances, and studio works. I carried it around in my head during subway rides, as well.

Eventually I stopped working full-time with children, but two years ago, during the cowardly named “migrant crisis,” I was asked to assist a sanctuary church with a children’s program. The church was welcoming recently arrived families, mostly from Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. The grown-ups were applying for asylum and the children needed something to do. My former training was in developing an “emergent curriculum,” a child-led approach where teachers eavesdrop and take notes on what the children are saying and doing, what materials they ignore, and which ones are irresistible. I planned to use the same system here.

Children of all ages came; we even had young adults wanting to join the activities. I chose clay and cardboard as our core materials, because I needed an adaptable material that would appeal to multiple age groups. I had experience presenting clay to my former preschool students, so I tried to replicate and edit some of the activities. The volunteers and I were getting ready to work, but as soon as we showed the clay to the group, one of the children said, “La selva” — “the jungle.” We were unsure what jungle she was talking about. She looked scared until other children seconded the message: “La selva, la selva!” Soon we realized that they were talking about the journey through the Darién Gap rainforest on the Colombia-Panama border.

We were unsure how to respond. Did we need to change the material because it was triggering the children? Or was it better to redirect the conversation? We let the children tell us their stories, and while they narrated the trauma of the crossing, they also rolled and pinched the clay, transforming it into mango trees, kittens, fruit baskets, snowmen, and other creatures. The children were holding two stories in their bodies: one that narrated a harrowing experience, another that cultivated fantasy and joy.

I kept with me the intimacy that the children shared during those years. It is a reminder that my entire body is an extension of my art and making. My mispronounced words, my Mexican accent, and my non-sequiturs come with me to the studio and the streets.

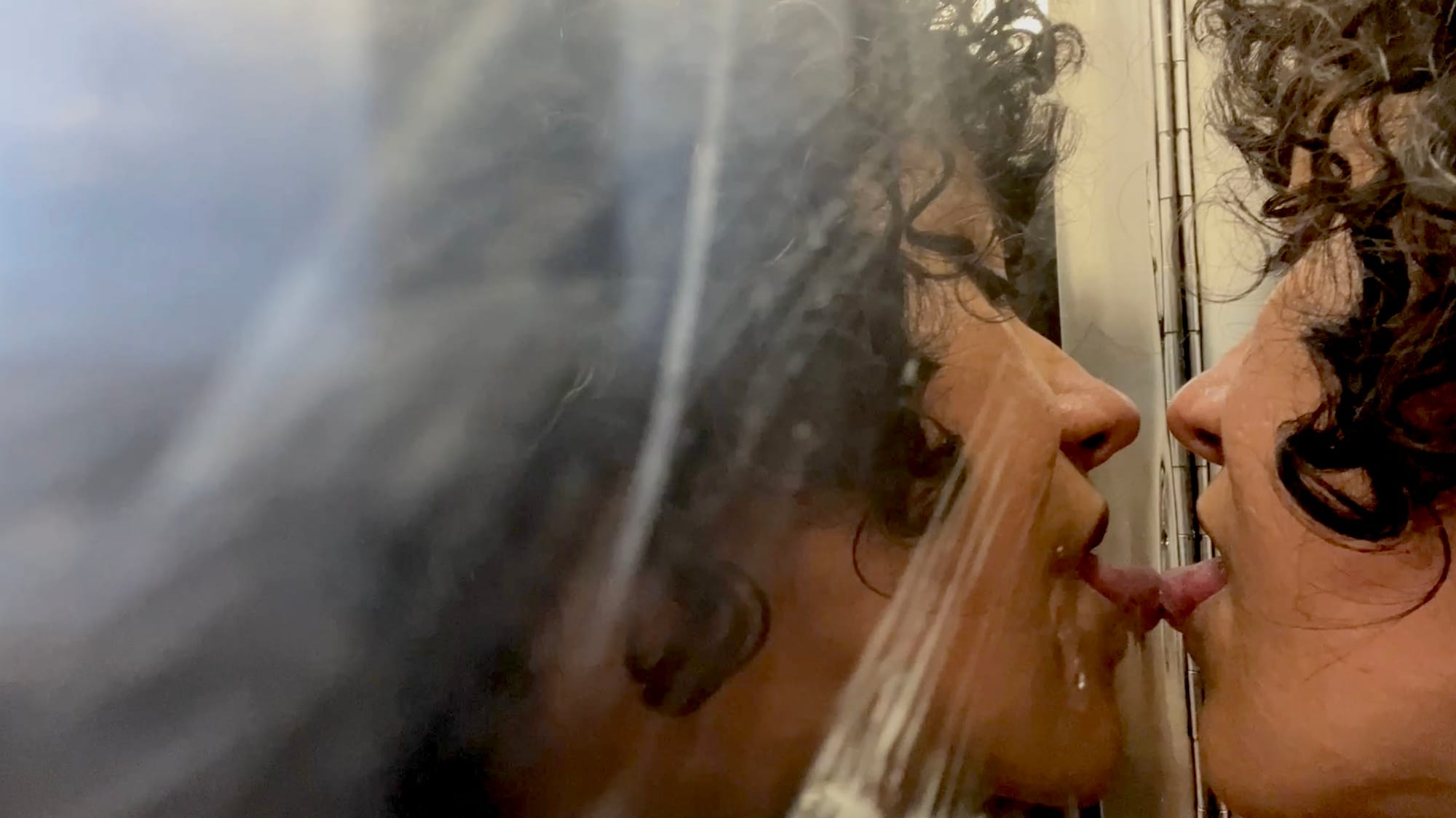

In 2016, I declared a corner dotted with round sewer covers in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, my neighborhood, my temporary theater, where I presented a series of 10 performances. Among other actions, I made my own ink, chewing and spitting activated charcoal and burnt tortillas into a bowl. Later, during the COVID-19 pandemic, my friend Jenny Nichols from the now-closed Soloway gallery in Williamsburg invited me to perform. The gallery had a small front window display where I installed a plexiglass coated with activated charcoal and other concoctions. From inside, I wrote on the panel with my mouth. Like a radio, I was channeling the songs, prayers, political slogans, and poems that I memorized in my childhood and adolescence in Mexico City. My face was glued to the plexiglass while licking and removing sections of the charcoal mixture. The audience was outside listening to my singing and declaiming through an amplifier.

More recently, during my subway commutes, I developed a close relationship with the punched metal panels on the R46, R62, and R68 trains. I noticed that, when sitting close to the last seats next to the car doors, one’s own reflection on the steel appears manipulated or injured. For the commute’s length, I carried those wounds. I sanitized the panels, then I kissed them and licked them as if I was loving myself. I was caressing and soothing whatever rage was responsible for the craters.

I’ve been remembering that when I was a child, and my dad was driving us to visit our grandparents in Guanajuato, México, I licked the mist on the windows generated by our breath; I was then able to better see the night.