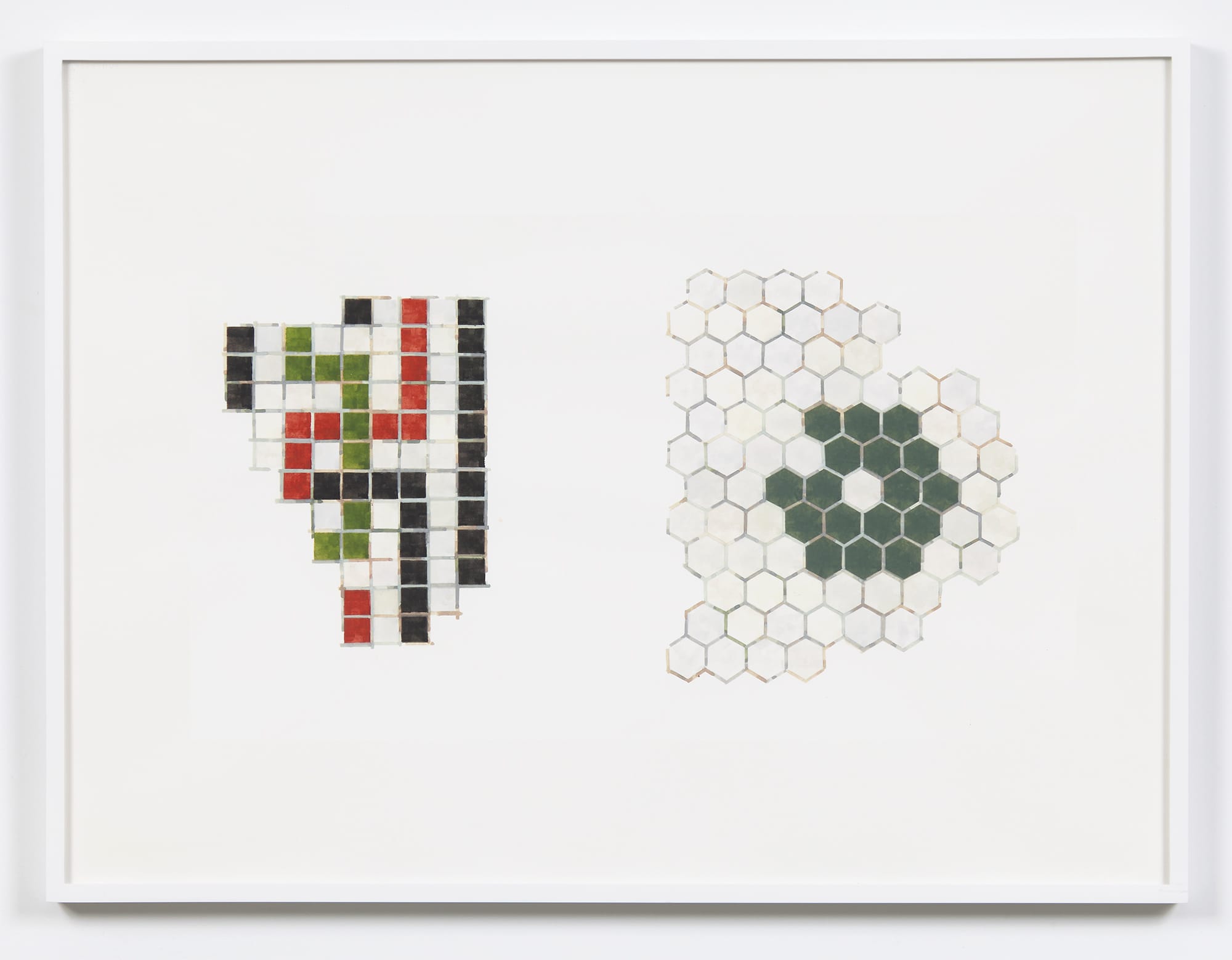

In 1992, Julia Fish and her husband, the sculptor Richard Rezac, moved into a two-story brick storefront on Hermitage Street in Chicago. That same year, she began reflecting on the particulars of the home, designed by Theodore Steuben and built in 1922, starting with the hexagonal tiles in the foyer area connecting the interior to the street. Since those first works, Fish has further transformed the act of looking into an intricate modality that visualizes the interplay of geometry and architecture, wood grain patterning and Johann Sebastian Bach’s fugal compositions, prismatic light and musical notes.

While I have followed Fish’s work as closely as possible over the years, and written about it a number of times, I cannot always say that I know what she is trying to do, nor does it matter. It is similar to how I feel when I view the paintings and drawings of Alfred Jensen or read Louis Zukofsky’s long poem A or his homophonic translations of Catullus: You go wherever they lead you, not because you immediately know what is going on, but because of the deep, inimitable pleasure of connecting your self-reflective thinking to the external experience of looking or, in Zukofsky’s case, reading.

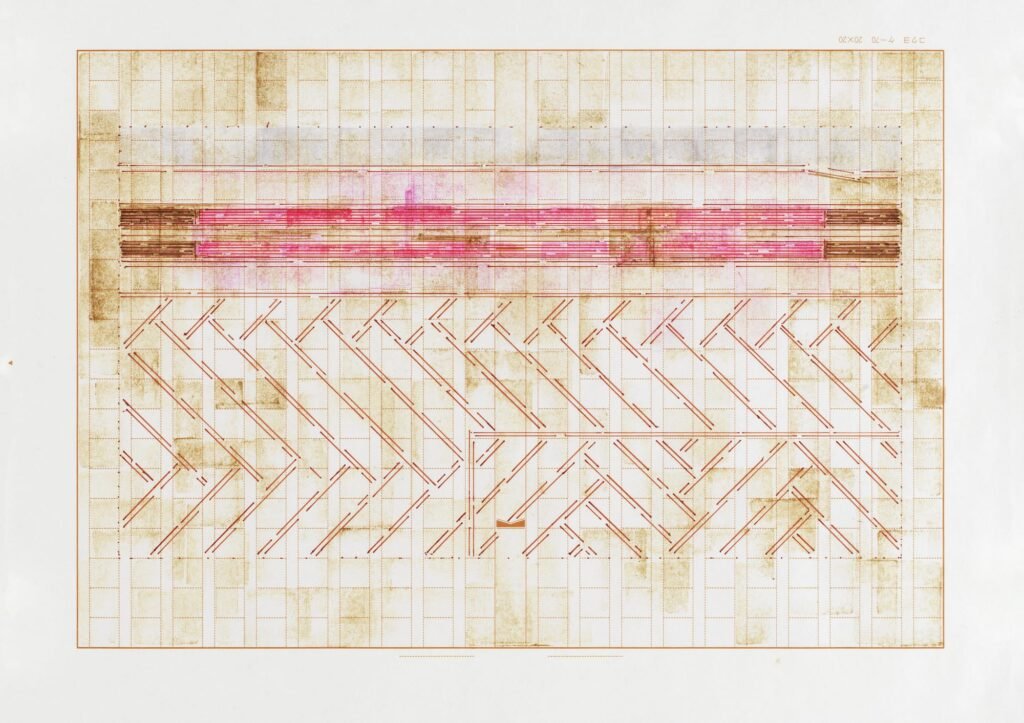

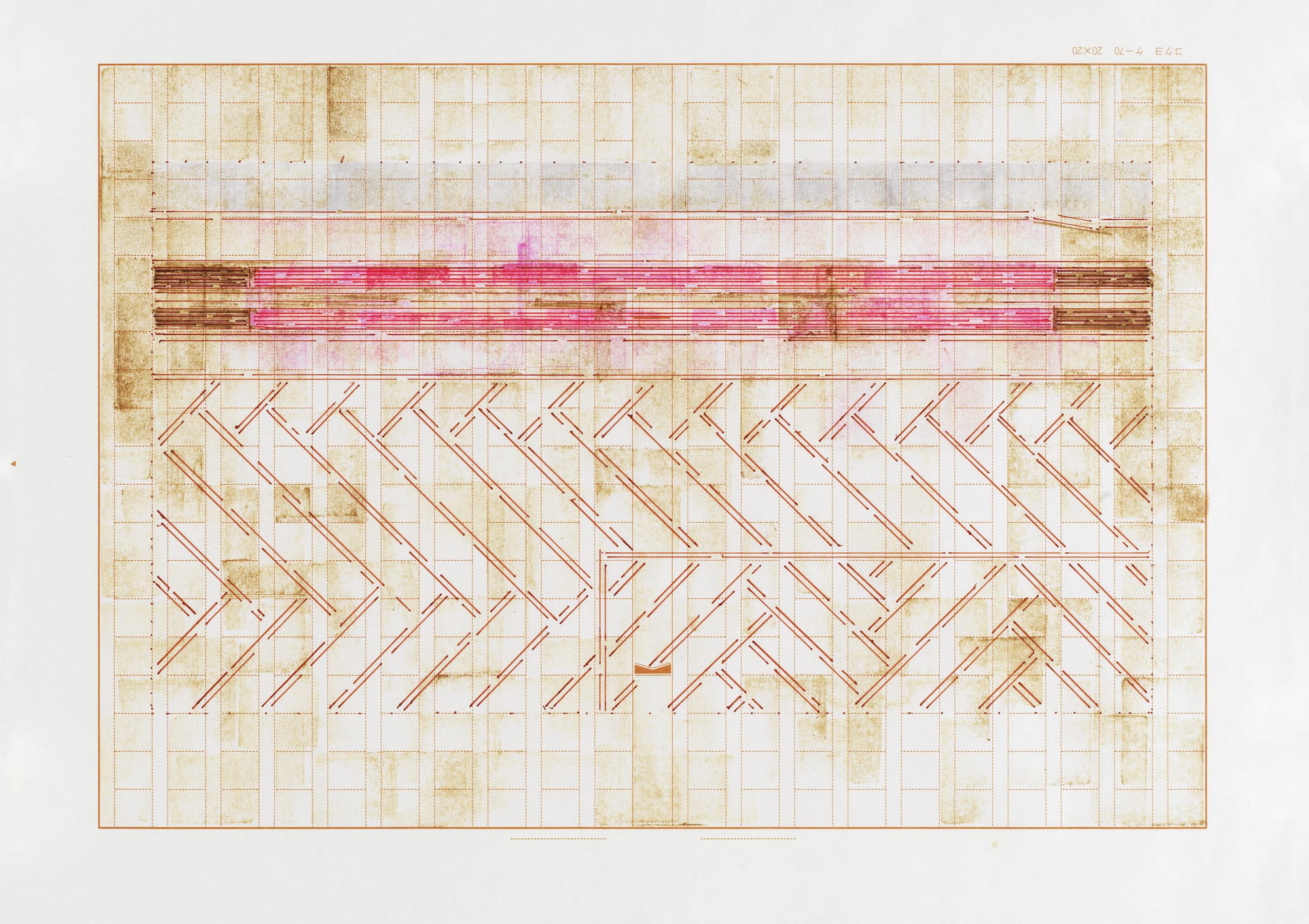

This pleasure, which I can find in few artists other than Fish, led me to her current exhibition, Transcriptions, Apparitions, at David Nolan Gallery. The 25 works on view include a painting, a dye-sublimation print on metal mounted on wood, unique hand-stamped drawings, gouaches, ink on paper pieces, and interventions around the Upper East Side townhouse gallery’s fireplace, in the seams of the woodgrain, and where the wall meets the floor.

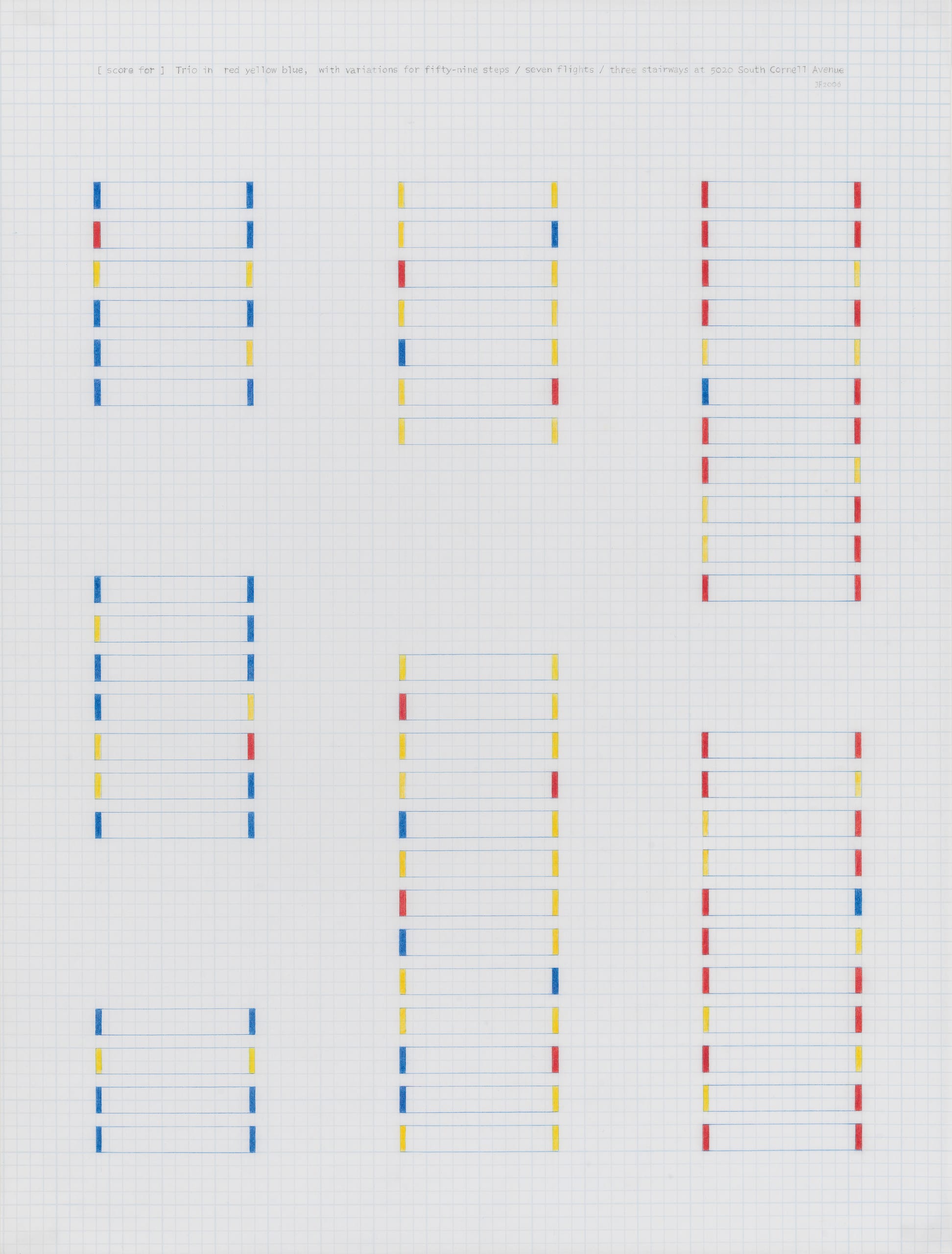

One work that caught my attention in the exhibition was “[ score for ] Trio in red yellow blue, with variations for fifty-nine steps/seven flights/three stairways at 5020 South Cornell Avenue” (2006), which Fish made in response to the new location of Chicago’s Hyde Park Art Center. Founded in 1939, it was the site of many famous exhibitions organized by artist and curator Don Baum in the late 1960s, including three titled Hairy Who? (in 1966, ’67, and ’68).

Looking at the work, which is about history, memory, and time, I asked myself, how do all of these elements connect? The colored pencil and graphite drawing on graph paper is composed of seven stacks of equally sized horizontal rectangles arranged in three vertical rows that add up to the title’s 59 steps. Each step is bookended with a primary color. While I am sure there is a logic to her color choice, I could not deduce it from the work itself and ultimately it did not matter. At once visual and intellectual, the delight is in the looking. The combination of rigor, austerity, simplicity of means and material, and the joy of making that comes through was enough to send my mind spinning in various directions — including realizing that I see stairs as serving a single purpose, but seldom think of them musically as a kind of score.

Fish’s rigorous, nuanced, and materially delicate transcriptions of the intersection of light, physical place, and historical exhibition memorialize the apparitional nature of time passing through the unique architecture of a site. Sure, the place is tied in with art and artifacts (exhibitions, announcements, guestbook, and posters), but her interest isn’t in the nostalgia of recreating or recapturing the past. She slows time down by homing in on a manifestation of its overlooked presence.

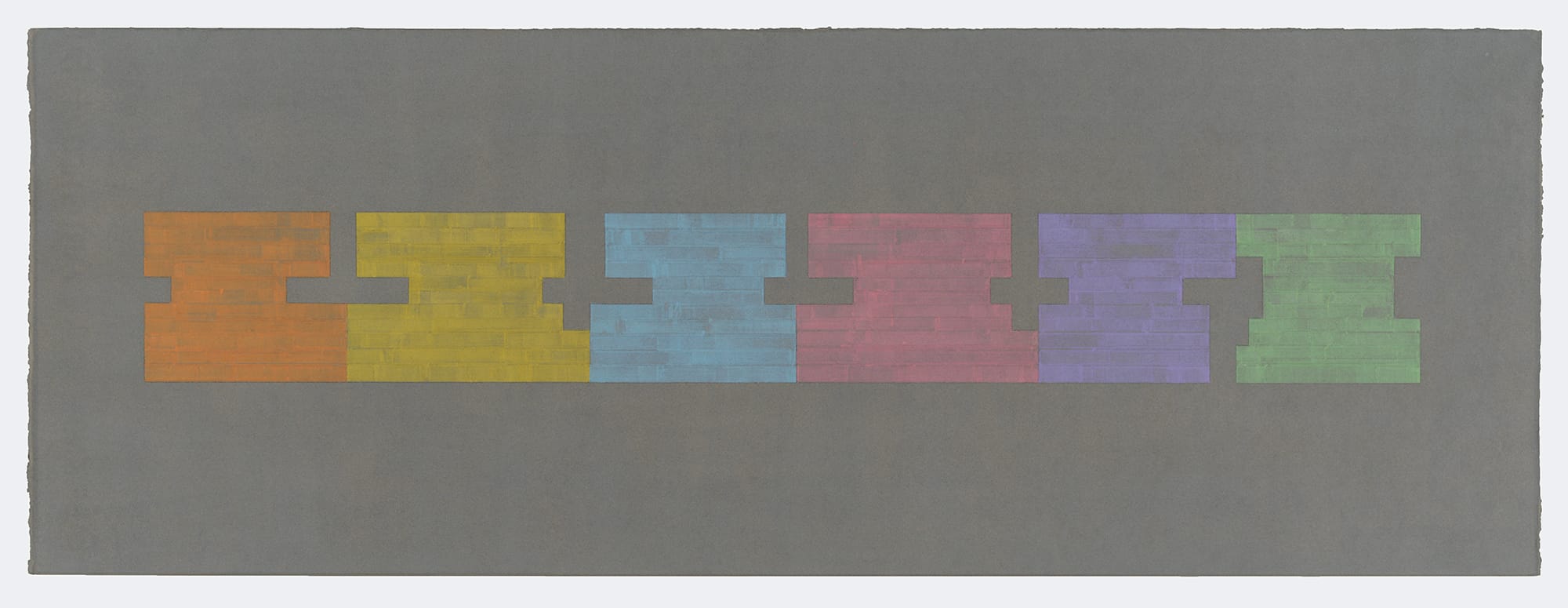

In “Study for Threshold – Plan : [ las meninas ] [ spectrum : east to west over grey ]” (2018), Fish applies pale gouache across the color spectrum on gray paper, connecting architectural thresholds to the shape of the dresses worn by the five-year-old Infanta Margaret Theresa and her entourage of maids of honor in “Las Meninas” (1656) by Diego Velasquez. By link these architectural features with Velasquez’s painting, which is arguably the greatest depiction of a particular moment in time in art, Fish invites us to contemplate how we engage with a work of art as well as reflect upon our own mortal passage. Rather than making a literal association between her work on paper and “Las Meninas,” she encourages us to contemplate the wider implications of the visual and tactile subtlety of the piece. Art is never solely about art, no matter how abstract. We are always crossing thresholds, entering a new and changing world.

Although Fish never makes any grand claims about her work, there were times during the exhibition that I felt she was after something mystical. Her devotion to seeing the magical in the ordinary is unrivaled. Like Bach, Fish believes that art is a medium capable of acknowledging divine presence — things seen and not looked at, Jasper Johns said about his choice of ordinary subjects. Fish focuses in on things on which the light has landed or brushed by, at once momentary and prolonged, and unseen by many. She sees auras and apparitions.

Julia Fish: Transcriptions, Apparitions continues at David Nolan Gallery (24 East 81st Street, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through February 14. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.