Editors’ Vox is a blog from AGU’s Publications Department.

Meteorological tsunamis, or meteotsunamis, are long ocean waves in the tsunami frequency band that are generated by traveling air pressure and wind disturbances. These underrated phenomena pose serious threats to coastal communities, especially in the era of climate change.

A new article in Reviews of Geophysics explores all aspects of meteotsunamis, from available data and tools used in research to the impacts on coastal communities. Here, we asked the authors to give an overview of these phenomena, how scientists study them, and what questions remain.

In simple terms, what are meteorological tsunamis or “meteotsunamis”?

Meteotsunamis are tsunami-like waves that are not generated by earthquakes or landslides, but by atmospheric processes.

Meteotsunamis are tsunami-like waves that are not generated by earthquakes or landslides, but by atmospheric processes. Their formation requires a strong air pressure or wind disturbance—typically characterized by a pressure change of 1–3 hectopascals over about five minutes—that propagates at a “perfect” speed, allowing long ocean waves to grow. In addition, coastal bathymetry must be sufficiently complex to amplify the incoming waves.

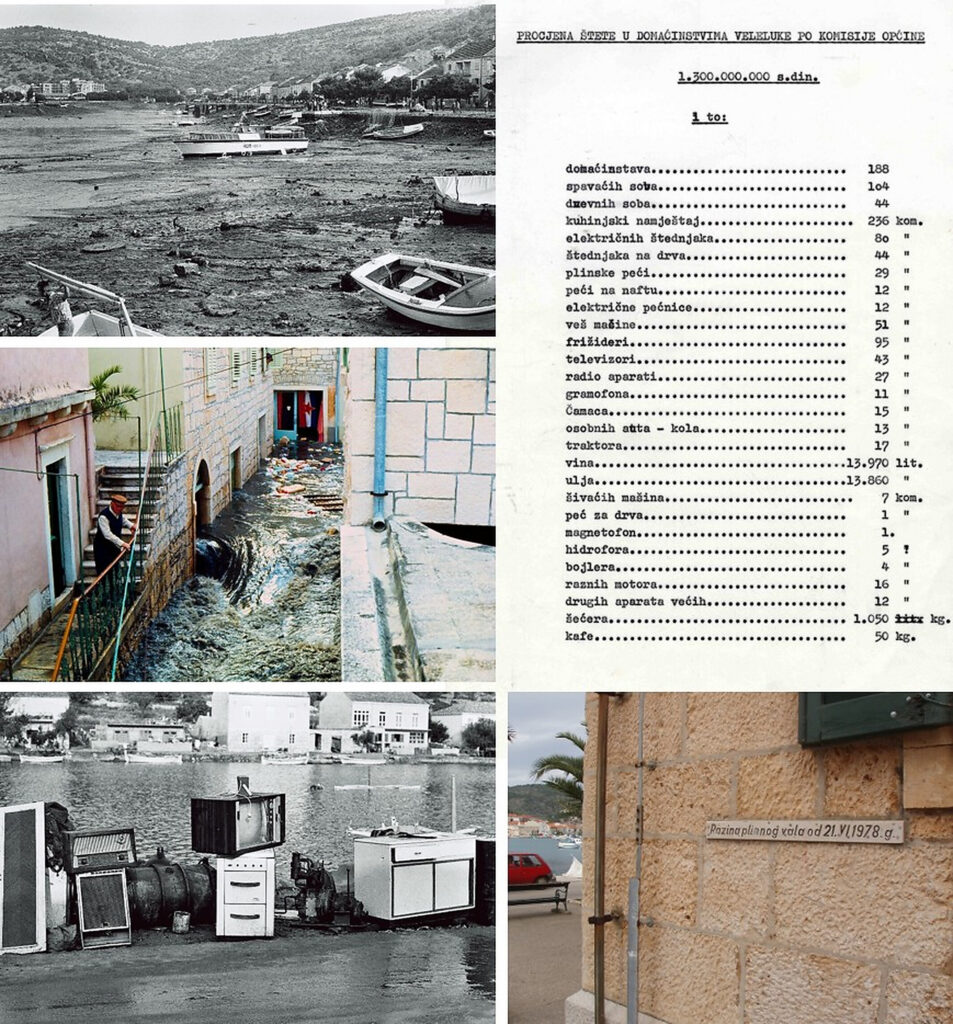

Meteotsunamis are less well known and, fortunately, are generally less destructive than seismic tsunamis. Nonetheless, they can reach wave heights of up to 10 meters and can be highly destructive. One of the most damaging events occurred on June 21, 1978, in Vela Luka, Croatia, where damages amounted to about 7 million US dollars at the time. Meteotsunamis can also cause injuries and fatalities, as unfortunately occurred on January 13, 2026, during the recent Argentina meteotsunami.

What kinds of hazards do meteotsunamis pose to humans and society?

Meteotsunamis are characterized by multi-meter sea level oscillations and, at times, strong currents. As a result, they can flood waterfront areas and households, while strong currents may break ship moorings and disrupt maritime traffic, as occurred in 2014 in Freemantle, Australia. An even greater danger comes from rip currents, which can sweep swimmers away from shore. A notable example is the July 4, 2003, meteotsunami that occurred under clear skies along the beaches of Lake Michigan and claimed seven lives.

How do scientists observe, measure, and reproduce meteotsunamis?

Much of the information on meteotsunamis comes from post-event observations. Following exceptionally strong events, scientists often visit affected locations to conduct field surveys, interview eyewitnesses, collect photos and videos, and estimate the extent and height of the meteotsunami along the coast. More precise information comes from coastal tide gauges and ocean buoys, as well as meteorological observations with at least minute-scale resolution.

Unfortunately, standard atmospheric and oceanic observing systems do not commonly operate at such high temporal resolution. For example, one of the oldest national networks—the UK tide gauge network operating for decades—still uses 15-minute sampling intervals. At the same time, most national meteorological services measure atmospheric variables at 10-minute or even hourly resolution, which is insufficient for meteotsunami research. Nevertheless, some oceanic and meteorological networks do provide appropriate sampling intervals, and even data from school-based or amateur networks can be valuable for research.

In addition, numerical modeling of meteotsunamis is now standard practice and includes both atmospheric and oceanic components. However, accurately reproducing meteotsunami-generating atmospheric processes—and thus meteotsunamis themselves—remains challenging. Addressing this issue and developing more accurate, high-resolution models is a key task for the modeling community.

Why has research on meteotsunamis shifted from localized to a global approach?

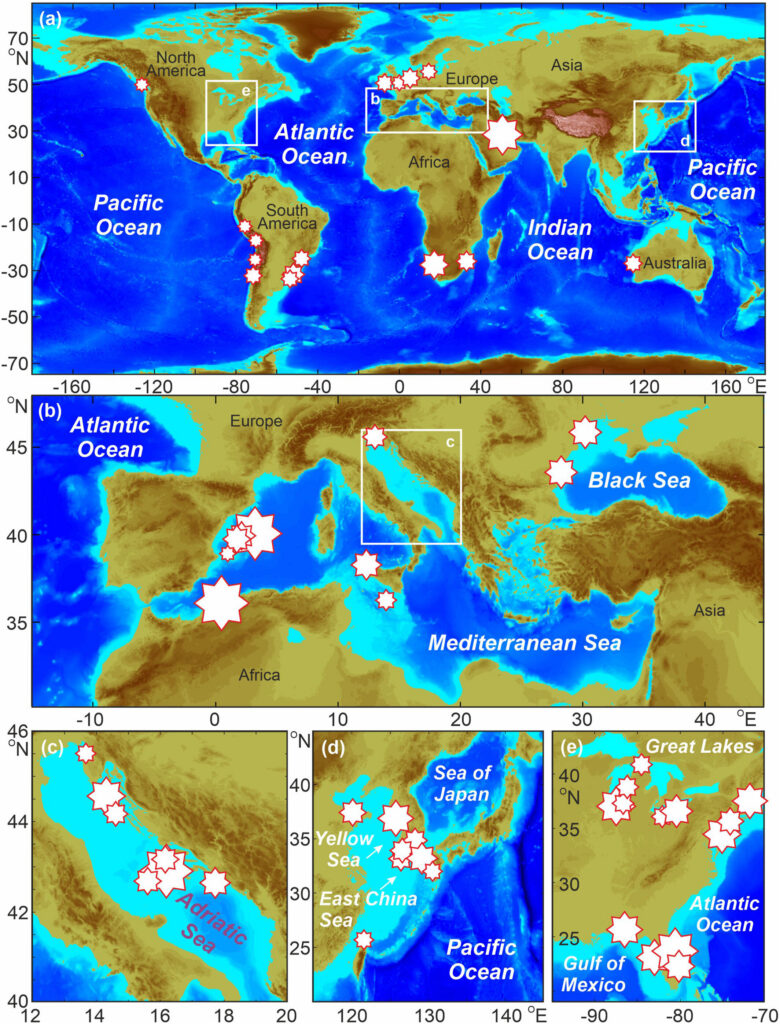

The strength of meteotsunamis strongly depends on coastal bathymetry. Within a specific bay, wave heights can reach several meters, while just outside the bay they may be only a few tens of centimeters. For this reason, meteotsunamis were historically observed and studied mainly at individual locations, known as meteotsunami hot spots. Over the past few decades, however, advances in monitoring and modeling capabilities, along with easier global dissemination of scientific results, have revealed that the same phenomenon occurs worldwide. Moreover, the recent availability of hundreds of multi-year, minute-scale sea level records has enabled researchers to conduct global studies and quantify worldwide meteotsunami patterns.

What are the primary ways that meteotsunamis are generated?

The generation of a strong meteotsunami requires (i) an intense, minute-scale air-pressure or wind disturbance that propagates over long distances (tens to hundreds of kilometers), (ii) an ocean region where energy is efficiently transferred from the atmosphere to the ocean, for example through Proudman resonance—a process in which long ocean waves grow strongly when the speed of the atmospheric disturbance matches the speed of tsunami waves, and (iii) coastal bathymetry capable of strongly amplifying long ocean waves. Funnel-shaped bays are particularly prone to meteotsunamis. These events can also be generated by explosive volcanic eruptions, such as the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai eruption in January 2022, which produced a planetary-scale meteotsunami.

How is climate change expected to influence meteotsunamis?

At present, this is not well understood. Only two published studies exist, and both suggest a possible increase in meteotsunami intensity in the future due to an increased frequency of atmospheric conditions favorable for meteotsunami generation. However, no global assessment is currently available, as climate models are still unable to reliably reproduce the kilometer- or sub-kilometer-scale processes required to simulate meteotsunamis.

What are some of the recent advances in forecasting meteotsunamis?

Some progress has been made, but effective forecasting and early-warning systems for meteotsunamis remain far from operational. Improvements in atmospheric numerical models—currently the main source of uncertainty in meteotsunami simulations and forecasts—are expected in the coming decades, particularly through the development of new parameterization schemes that better represent turbulence-scale processes.

How does your review article differ from others that have covered meteotsunamis?

Our review introduces a new class of meteotsunamis generated by explosive volcanic eruptions.

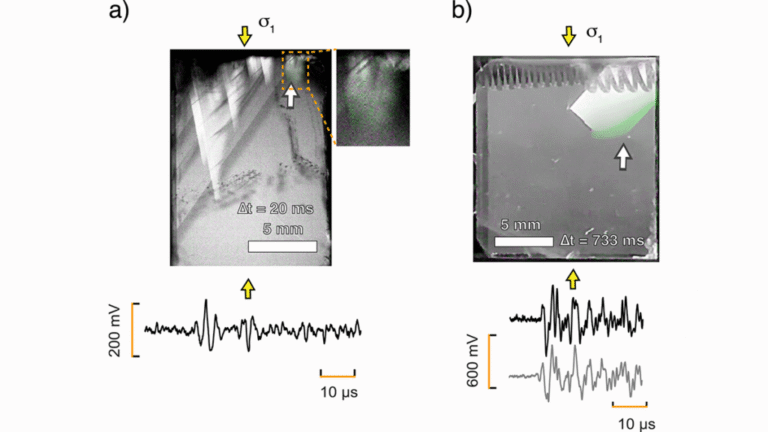

The most recent comprehensive review of meteotsunamis was published nearly 20 years ago, making this review a timely synthesis of the substantial advances made over the past two decades. In addition, our review introduces a new class of meteotsunamis generated by explosive volcanic eruptions, such as the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai event in January 2022. Such events were previously only sporadically noted, as the last comparable eruption occurred in 1883 with the Krakatoa volcano. Finally, recent findings show that meteotsunamis—much like seismic tsunamis—can radiate energy into the ionosphere, where it can be detected using ground-based GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) stations. This discovery opens a new avenue for future meteotsunami research.

What are some of the remaining questions where additional research efforts are needed?

Many challenges remain in the observation, reproduction, and forecasting of meteotsunamis. Most are closely linked to technological advancements, such as (i) the need for dense, continuous, minute-scale observations of sea level and meteorological variables across the ocean and over climate-relevant time scales, (ii) increased computational power, since sub-kilometer atmosphere–ocean models require enormous resources, potentially addressable through GPU acceleration or future quantum computing, and (iii) the development of improved parameterizations for numerical models at sub-kilometer scales. Ultimately, extending research toward climate-scale assessments of meteotsunamis is essential for accurately evaluating coastal risks associated with sea level rise and future extreme sea levels, which currently do not account for minute-scale oscillations such as meteotsunamis.

—Ivica Vilibić (Ivica.vilibic@irb.hr, ![]() 0000-0002-0753-5775), Ruđer Bošković Institute & Institute for Adriatic Crops, Croatia; Petra Zemunik Selak (

0000-0002-0753-5775), Ruđer Bošković Institute & Institute for Adriatic Crops, Croatia; Petra Zemunik Selak (![]() 0000-0003-4291-5244), Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Croatia; and Jadranka Šepić (

0000-0003-4291-5244), Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Croatia; and Jadranka Šepić (![]() 0000-0002-5624-1351), Faculty of Science, University of Split, Croatia

0000-0002-5624-1351), Faculty of Science, University of Split, Croatia

Editor’s Note: It is the policy of AGU Publications to invite the authors of articles published in Reviews of Geophysics to write a summary for Eos Editors’ Vox.

Citation: Vilibić, I., P. Zemunik Selak, and J. Šepić (2026), Tsunamis from the sky, Eos, 107, https://doi.org/10.1029/2026EO265002. Published on 3 February 2026.

This article does not represent the opinion of AGU, Eos, or any of its affiliates. It is solely the opinion of the author(s).

Text © 2026. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.