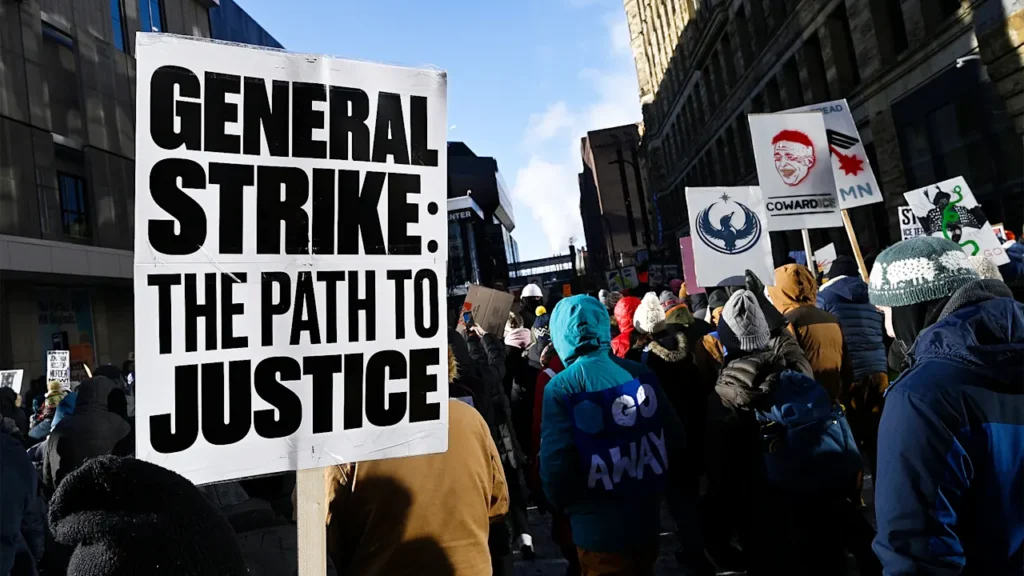

Today, thousands of Americans are participating in a general strike. The instructions are simple: no work, no school, no shopping. The aim is ambitious—to pressure the Trump administration to remove ICE from local communities.

The strike is a response to the fatal shootings of Alex Pretti and Renee Good in Minnesota. In the days since, calls for a nationwide shutdown have spread rapidly across social media, shared by activists, nonprofits, and everyday people urging a halt to economic activity. Celebrities including Pedro Pascal, Edward Norton, and Jamie Lee Curtis have amplified the message to their followers.

Some businesses—mostly small, independent ones—have heeded the call. Clothing label Misha and Puff, olive oil maker Brightland, and underwear brand Oddobody have all closed for the day, forgoing revenue as a form of protest. “The only thing the Trump administration responds to is the market,” says Polly Rodriguez, founder of the sexual wellness company Unbound Babes, who has shuttered her business for the day. “Our goal is to raise awareness today, link people to other resources, and gather donations for organizations on the ground in Minnesota.”

The Organizers Behind This Strike

Although the strike has been organized in a decentralized way, with no single leader at the helm, many participants have turned to the website and Instagram account of The General Strike US, which offer guidance about organizing a general strike. Eliza Blum, a longtime labor organizer, built the site in 2022, alongside other activists.

“I wouldn’t say I’m a founder,” she says. “We’re very much a non-hierarchical, decentralized network.”

Through her work with Fight for $15, the campaign for a $15 minimum wage, Blum saw firsthand how strikes forced companies and policymakers to pay attention. As the Trump administration pursued what she viewed as increasingly authoritarian policies, she began to see labor as a central tool of resistance.

“When Roe v. Wade was overturned, I hit a personal breaking point,” she tells me. “Protesting in the streets, holding signs, calling our representatives—it wasn’t enough. We live in an extremely capitalist society where our greatest weapon is our labor. If working people stopped working, we could shut down the country until our demands were met.”

Other prominent voices have echoed that view. “What does a national civic uprising look like?” Robert Reich, a U.C. Berkeley law professor, wrote in his Substack last April. “It may look like a general strike—a strike in which tens of millions of Americans refuse to work, refuse to buy, refuse to engage in anything other than a mass demonstration against the regime.”

The General Strike website calls for people to sign a “strike card,” pledging their participation in future actions. The long-term goal, Blum says, is to secure commitments from 3.5% of the U.S. population—roughly 10.5 million people. The figure comes from research by political scientists Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, which suggests that when 3.5% of a population engages in sustained protest, authoritarian governments are likely to collapse.

So far, about 435,730 people have signed the pledge. Once the number reaches 10.5 million, organizers plan to coordinate a nationwide strike. In the meantime, Blum argues that smaller, recurring actions are essential for building momentum.

Reich agrees. “[It will take more than] just one general strike, but a repeating general strike,” he writes. “A strike whose numbers continue to grow and whose outrage, resistance, and solidarity continue to spread across the land.”

Last Friday, hundreds of Minnesota businesses closed as a show of opposition to ICE. For Blum, this was an important turning point. She saw local unions come together with community organizers to work collectively. This local strike had an impact, making headlines in the New York Times and the BBC. “It was the first time, since I’ve been doing this that I saw a general strike actually happen,” she says.

The History of General Strikes

The term “general strike” is most closely associated with events in Britain in 1926, when trade unions organized coal miners to walk off the job after mine owners slashed wages and lengthened working hours. Workers across other industries—including transportation, printing, and manufacturing—joined in solidarity, bringing large parts of the country to a standstill.

The government quickly intervened, framing the strike as a threat not just to employers, but to the nation itself. Union leaders soon found themselves in direct confrontation with the state, and after nine days, they called off the strike.

“It was a total failure,” says Jonathan Schneer, a British historian whose book, Nine Days in May: The General Strike of 1926 comes out this summer. (Disclosure: Schneer is my father-in-law.) “The coal miners were ultimately left isolated and forced to work under even worse conditions.”

Schneer notes that while today’s general strike draws inspiration from the events of 1926, there are also crucial differences—most notably the level of coordination involved. In England at the time, between a third and half of all workers were unionized, and labor leaders were able to mobilize a significant share of the population. “It took enormous organization to pull something like that off,” Schneer says.

Nearly a century later, the landscape has shifted. Today’s action is being organized largely online, at a moment when labor unions are far weaker than they were in early-20th-century Britain. The United States also has a much larger and more geographically dispersed population. What remains constant, however, is the central role of capitalism in everyday life—and the idea that halting economic activity can still be a powerful way to command the government’s attention. When enough people participate, Schneer argues, the signal is impossible to ignore.

The Demands

For Blum, the fact that the strike isn’t centrally organized is one of its strengths. Like other activist groups that emerged during Trump’s second term—including Indivisible—she believes organizing works best at the local level, allowing communities to respond to their own conditions. Her role, she says, is less about directing the movement than equipping others with the tools to organize within their own networks.

That decentralized structure also means there is no single, unified set of demands. The General Strike US website lists a wide range of causes worth striking for, from universal healthcare to voting rights. For now, however, participants appear to be coalescing around a more immediate goal: removing ICE from local communities. On social media, posts frequently express solidarity with protesters in Minnesota and call for the abolition of ICE altogether.

While organizers encourage people to stay home from work and school, the most accessible form of participation is refusing to spend money. A number of small businesses have chosen to close for the day in solidarity, though no major corporations have followed suit.

“I am very disappointed in the lack of reaction from companies that are far more powerful and influential than we are,” says Melody Serafino, founder of the communications agency No.29, which also shuttered operations. “Let me be clear: posting on Instagram and shutting down our business for a day is not brave. Real courage is being exemplified by the people on the ground who are putting their lives at risk.”

For Blum, however, this moment is just the beginning. She sees the current action as the first in what she hopes will be a series of escalating strikes—and says it is already producing results. In recent days, tens of thousands of people have signed strike cards through her website. There is still a long road ahead to reaching the 3.5% threshold of the U.S. population, but the numbers, she says, are rising steadily.

“Movements that reach that level of participation never fail to bring about radical change,” Blum says. “But it takes time.”