For nearly two decades, Washington tried to bend Venezuela through pressure without pulling the trigger. This was in the form of sanctions, diplomatic isolation, and bounties. It was slow, messy, and often ineffective. In January 2026, that approach ended.

What happened next was the final step of a long strategy that moved from economic strangulation to outright military control.

The Calm before the Storm

For much of the 20th century, the United States and Venezuela had a quiet, functional relationship. Venezuela supplied oil. American companies refined it. Politics rarely interfered. That balance broke in 1999 with the rise of Hugo Chávez. Chávez did not just nationalise oil assets. He took control of oil profits, rewrote contracts midstream, and openly framed the US as an imperial rival while building ties with China, Russia, Iran, and Cuba.

For Washington, the issue was not democracy or human rights at first. It was rather about predictability. A country sitting on the world’s largest oil reserves had stopped playing by the old rules.

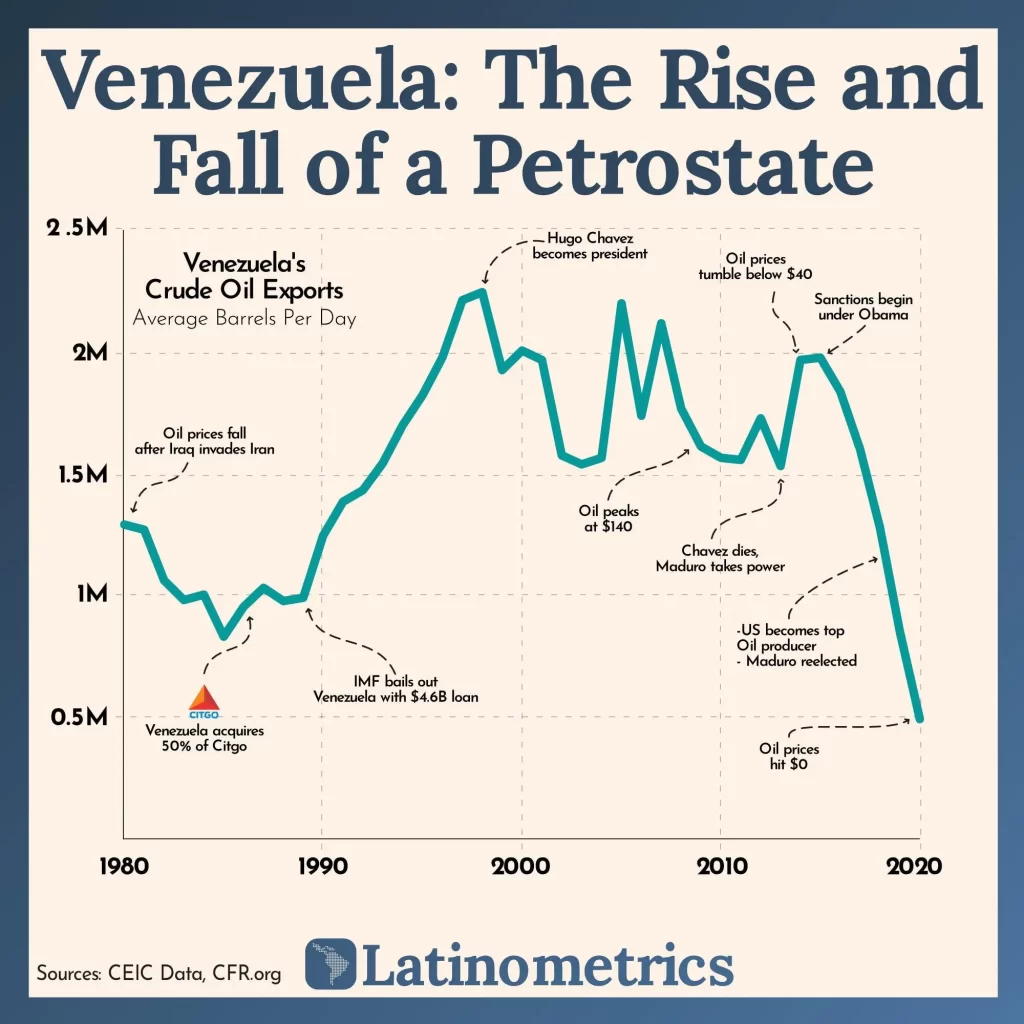

For years, the US absorbed this tension rather than escalating it. The reason was oil. American Gulf Coast refineries were deeply dependent on Venezuela’s heavy crude, and cutting ties would have hurt US energy security as much as it hurt Caracas. That constraint faded after 2010. The shale boom more than doubled US oil production within a decade and turned the country into the world’s largest producer. Once dependence dropped, tolerance dropped with it. Sanctions that had once been politically risky became affordable. This is where the modern sanctions regime begins.

From Maximum Pressure to Direct Action

From 2006 onward, the United States limited arms sales, downgraded diplomatic ties, and imposed targeted sanctions on Venezuelan officials. The idea was simple. It was just to hurt the elite, not the entire country.

That logic collapsed after 2017. Under Donald Trump’s first term, sanctions expanded from individuals to the entire Venezuelan economy. Financial markets were cut off. Oil exports were blocked. By 2019, the oil embargo removed Caracas’s main source of revenue, while Washington recognised Juan Guaido as interim president.

When sanctions failed to remove Nicolas Maduro, the strategy changed again. The US reframed Venezuela as a criminal enterprise. In 2020, the Justice Department indicted Maduro for narco-terrorism and put a $15 million bounty on his head. By 2025, that bounty rose to $50 million. This shift mattered. Once a government is treated as a syndicate, military action becomes easier to justify.

By late 2025, air strikes on “drug-smuggling” vessels gave way to attacks on Venezuelan infrastructure. On January 3, 2026, Operation Absolute Resolve crossed the final line. Air defences were neutralised. Special forces captured Maduro. Sanctions had given way to strikes.

What happened in this period is dramatic. Oil production fell from about 2.4 million barrels/day in 2015 to under 700,000 by 2023. Oil revenues accounted for over 90% of export earnings, so sanctions hit the state, not just the regime. Their GDP contracted by over 70% between 2013 and 2021

The “Donroe Doctrine” and Western Hegemony

This moment fits into a much older pattern. Since the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 and the Roosevelt Corollary of 1904, the United States has claimed a special right to intervene in Latin America. What Trump did was not invent a new doctrine, but revive it openly.

Call it the Donroe Doctrine. A mix of Donald Trump’s unilateralism and America’s historic belief that the Western Hemisphere is its strategic backyard.

The difference this time is China. Over the past two decades, Beijing has become South America’s largest trading partner. It loaned Venezuela over $60 billion, built ports, financed infrastructure, and tied the country into the Belt and Road Initiative. China became Venezuela’s largest creditor and one of its top oil buyers after US sanctions. Russia supplied weapons, and Iran supplied drones.

From Washington’s view, Venezuela stopped being just a failed socialist state. It became a Chinese and Russian foothold, sitting three to four hours from Florida. Trump’s return to office in 2025 came with a conviction that containment had failed. The response was escalation, not diplomacy.

Maduro’s Fall as a Regional Warning

Maduro’s capture was not only about Venezuela but a message to Nicaragua, Cuba, Bolivia, and, for that matter, to any government in the region flirting with Beijing or Moscow.

The logic was blunt. If the US can seize a sitting president, no leader is untouchable. Sanctions, legal charges, and military force now sit on the same ladder of escalation.

This also explains why Washington rejected Maduro’s last-minute offer to open oil and gold sectors to American companies and cut ties with China. From a narrow economic view, the deal made sense. From a strategic view, it was too late.

Over 7.7 million Venezuelans have left the country since 2014, the largest displacement in Latin American history. The objective had shifted from leverage to example.

The Oil-for-Reconstruction Gamble

Publicly, Washington framed the intervention around drugs, democracy, and human rights. Privately, oil still sits at the centre. Here’s the thing. The US does not need Venezuelan oil in volume. It needs it in type.

Most American shale oil is light crude. But US Gulf Coast refineries are built for heavy crude. About 70% of US oil imports today are heavy. That oil mainly comes from Canada and Venezuela.

Venezuela also holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, most of it being heavy and perfectly suited for US refineries. Add to this the Arco Minero region, rich in gold, coltan, and rare minerals essential for electronics and electric vehicles.

The post-Maduro plan appears straightforward: stabilise the country, reopen the energy sector, invite Western companies back, and use oil revenue to fund reconstruction under US supervision.

It is a gamble. Iraq showed how fragile occupation-led rebuilding can be. But Washington seems willing to take the risk.

From Regime Change to Border Security

The final shift is the most important and definitely rhetorical. Trump no longer sells this as regime change. He sells it as border security.

Drug cartels and syndicates are now labelled terror organisations. Migration is framed as a national security threat. Venezuela becomes not a foreign war, but a domestic defence issue.

In other words, earlier, Venezuela was framed as a democracy problem. But by 2025, that language faded. Instead, Washington began describing Venezuela as a direct threat to US border security, linking the Maduro government to drug trafficking, gangs, and migration.

Conclusion

Border security is a domestic issue, not a diplomatic one. It allows the use of military force without calling it a war and without waiting for international approval. Once Venezuela was framed as a security threat rather than a political problem, sanctions no longer looked sufficient. Direct action could be sold as a defence.

This framing helps politically. It blurs the line between foreign intervention and homeland protection. That is what makes January 2026 so unsettling for the region. If Venezuela can be taken over under the banner of drugs and security, others may follow.

Venezuela’s collapse has many authors: Hugo Chávez’s redistribution without investment, Maduro’s corruption and repression. But geopolitics finished the job. The lesson is not that Venezuela was innocent, or that the US acted selflessly. It is that power, not principles, that still governs international order. And in Trump’s Latin America doctrine, power no longer waits patiently.

Written By – Krishna Murugappan

Edited By – Shiv Talesara

The post The Dramatic Shift in Trump’s Latin American Doctrine appeared first on The Economic Transcript.