A creepy account that’s almost certainly using AI to generate videos of imaginary New Yorkers criticizing mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani raises a frightening prospect: that deepfakes could be used not just to impersonate politicians, but also constituents.

Accounts on several social media platforms – which are using similar profile pictures and appear to be linked – are calling themselves the Citizens Against Mamdani. In recent days, these accounts have posted confessionals and rants from “New Yorkers” slamming Mamdani for his – alleged – anti-Americanism, plans to hike taxes, and false promises on rent and transportation. They appear to be trying to imitate the diversity of New York, and many of the videos feature some of the city’s classic accents.

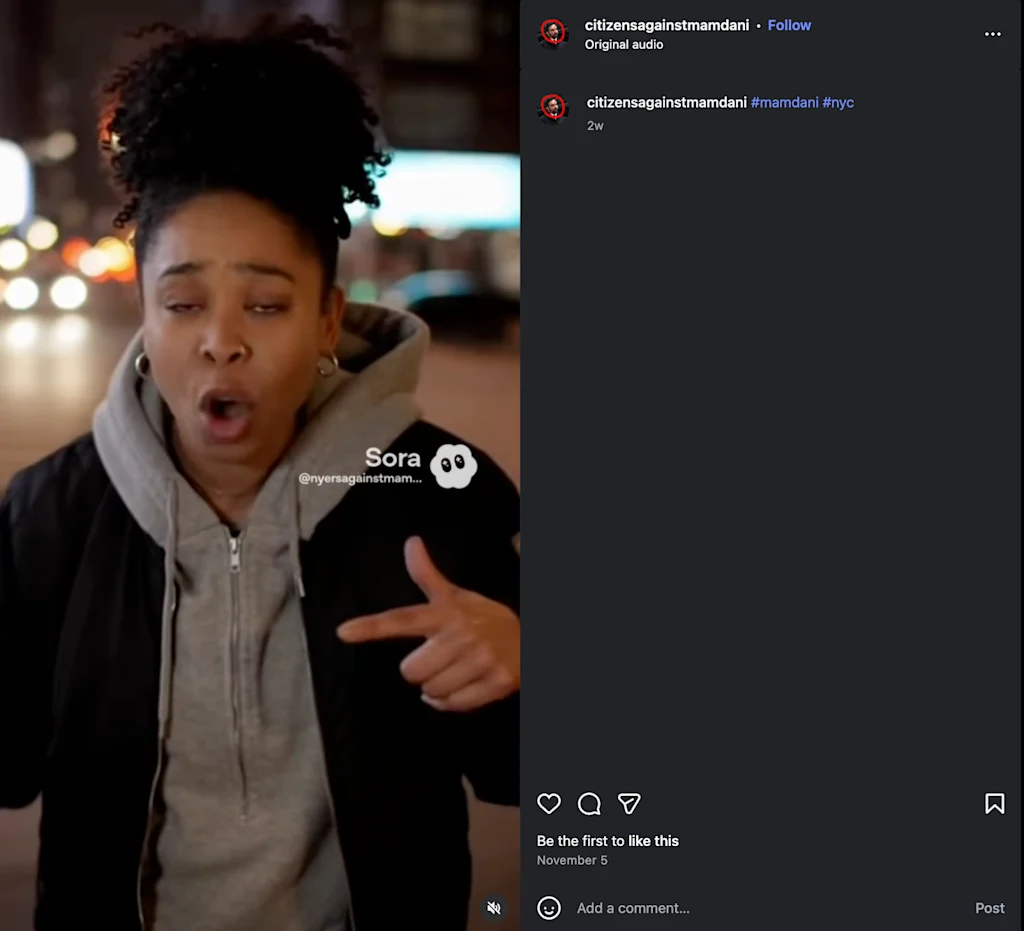

While none of the videos have gone viral, they have shown up on TikTok, Twitter, and Instagram, with some racking up tens of thousands of views. The TikTok account itself has about 30,000 likes. Fast Company reached out to the Instagram and TikTok pages but had not heard back at the time of publication.

“In the last election cycle, hiring human influencers to spread a particular message was all the rage. Now, teams don’t even need those personalities,” explains Emmanuelle Saliba, the chief investigative officer at GetReal Security, a cybersecurity firm that analyzes deepfakes. “GenAI has made such significant progress that campaigns and activists can use text-to-video to create hyper-realistic videos of supporters or detractors, and online consumers will be none the wiser,” she adds.

The online campaign shows how generative AI has, in essence, democratized astroturfing. “Astroturfing has been automated, and it’s pretty much undetectable without technology,” Saliba says — a notable evolution from the last election cycle, when it was more common for political operatives to hire influencers, she adds.

Using online tools to create a false impression of support or opposition to a movement or candidate isn’t new. In 2017, for example, bots were deployed to submit comments to the Federal Communications Commission, which was, at the time, considering new rules on net neutrality. But those types of campaigns have typically required at least some significant human effort, like operating a network of social media accounts or hiring influencers.

The rise of generative AI makes it far easier to create the mirage of political popularity online: Now, with just a few prompts and access to the right platform, you can simply generate videos of a bevy of real-ish seeming people.

A mirage

Of course, one of the challenges of deepfake detection is that there’s no absolutely sure-fire way to confirm that they’re generated by AI. With the anti-Mamdani videos, however, the evidence is overwhelming.

Beyond the visible Sora watermark – a label created by OpenAI to denote content created with the company’s technology – on some of the videos, the accounts have published numerous, similar videos at around the same time.

Another major hint is the objects in the background of the images, noted Siwei Lyu, a computer science professor who studies deepfakes at University of Buffalo.

Reality Defender, another firm that investigates AI-generated content, analyzed several of the videos using a platform it offers called RealScan and found that the odds they were manipulated were extremely high. The firm assessed that one video featuring a man in a blue hat, screaming “You all got fooled by Mamdani” had a 99 percent likelihood of being a deepfake. (It is impossible to score 100 percent: There’s no way to truly verify the ground truth of the content’s creation).

While it’s unclear the extent to which people have been actually convinced by the videos, the comments on them suggest at least some online users seem to be taking them seriously. “They show the illusion of broad support for or against an issue, and the people depicted in the videos are ordinary citizens. So it’s harder to verify their existence,” says Lyu. “This is yet another dangerous form of an AI-driven disinformation campaign.”

Astroturfing at scale

The accounts are a reminder that the cost of producing disinformation is lower than ever. It used to be that social engineering support for a particular cause would require real effort – for instance – investing in creating believable and realistic content, explains Alex Lisle, the chief technology officer of Reality Defender.

“Now I can define an LLM with a sentiment and a message I’m trying to give it, and then ask it to come up with what to say,” Lisle says. “And I can do that at a scale which before would require hours and hours of work,”manufacturing “hundreds of different quotes, thousands of different quotes, very, very quickly,” he adds.

Combining deepfakes with large language models allows political operatives to not only generate myriad scripts for what a deepfake can say, but also videos of people – with convincing voices – to actually spread those narratives. “You are now having a force multiplier,” Lisle continued. “In order to do this required multiple people and hours of effort. Now it just costs me computing.”

The problem expands beyond politics, emphasized Saliba, from GetReal. While Mamdani might be one example of a target, the low cost of creating this kind of content means that a business – or a loved one – could be the future subject of these kinds of disinformation campaigns.